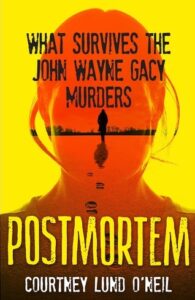

I’ve been thinking a lot about what happens when a crime is solved, a killer is caught, and the media has moved on to the next event. What remains of these stories? Who keeps these stories alive? These questions have been on my mind because I have been immersed in a crime case most have heard of: the John Wayne Gacy murders. He took the lives of 33 boys and young men in the Chicago area in the 1970s. Most know him as the killer clown, the democratic citizen, the businessman who threw backyard barbecues and enjoyed painting. We know this because his story has been circulating for nearly 50 years. And my larger question is, why?

Do we really care about his clown costumes or paintings? The man committed the worst acts a human can over and over again. I’m not convinced I should care too much about what he liked or how he was. Rather, I’m interested in learning the stories of those who had to survive his crimes, who had to live on despite the upheaval he caused in so many lives. I’m interested in this because I have a personal connection to one of those survivors—my own mom.

My mom, Kim Byers, was there the night Gacy took his final victim, Rob Piest. She was seventeen when she had to tell authorities Gacy was the last one seen with Rob. When Gacy told authorities this teen girl was making this up, she had to stand her ground. She had to face this man the world would come to know as the killer clown. And when the truth surfaced, when 29 bodies were exhumed from under Gacy’s house and another 4, including her friend Rob, were pulled from the river, she had to live on with the rest of her life. She had to testify at trial. She had to remember but also try to forget.

She had to remember the good: the beauty of young adult friendship, of working a high school job where co-workers felt like family, of the joy of developing a roll of film. But she had to try and forget Gacy, the one who was there the night Rob disappeared. She had to try and forget the feeling he gave her when he spread lies. Lies about never having spoken with Rob. Lies that this seventeen year old girl did not know what she was talking about or what she saw. As her daughter, I could not turn away from this feeling of wanting to know my mom as a seventeen year old girl. How had this event changed her? Because it had. Murder changes everything.

After Rob disappeared, my mother could not carry on with the innocence of what it meant to be a teenager. She had to be more cautious, more aware. If her friend went missing, who was to say she wasn’t next? And although these feelings were very real, as real as her role was in helping stop Gacy, the media and culture turned its eye and fascination on him. The survivors of this crime often floated to the periphery. This centering of Gacy, I believe, has been a real misstep in how we tell this story.

Don’t get me wrong, I acknowledge the value in preserving history. Keeping a record of Gacy and ilk like him is important, but celebrating him, mythologizing him, and putting him on a pedestal of importance is not necessary. Because doing so reinforces the feeling of power he had long chased; of exerting power over the powerless, and taking their voices, their lives so they could not speak back.

But my mom could speak back. When his 1980 trial came around, she had to point him out and say this was the man who took her friend Rob. He would not even look back at her. And she never forgot that. Gacy was found guilty. He would never be free to roam the streets of Chicago, scoping out his next victim, again.

We can rethink stories of true crime by illuminating the lives on the periphery, the survivors, and tell a new story.When a crime occurs, we have been quick to study the act of violence, often looking immediately and only at the perpetrator. Take a look at any news story. This has been the DNA of reporting on violence for a long time. But it’s important to not become numb to acts of violence, and instead: stay cognizant. Make space for other stories, and examine the ripple effects.

***