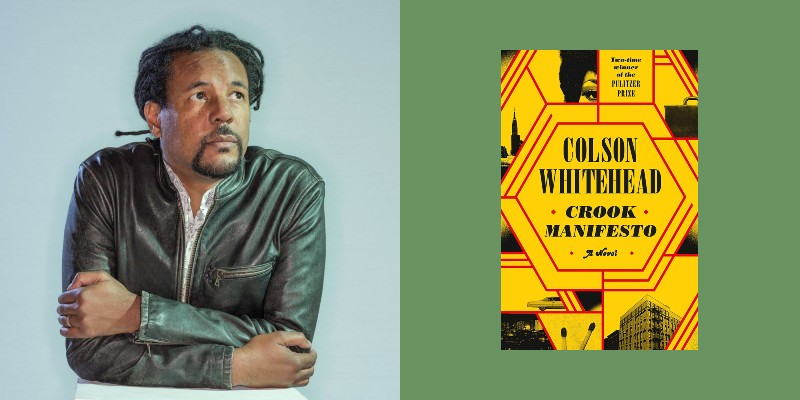

I’m on the record with all my lavish praise for what Colson Whitehead is doing, which is nothing short of a monument to crime fiction—and to New York City. I’m not sure what else there is to say about the man’s work except, I suppose, to urge readers once again, if somehow they haven’t already been persuaded, to give themselves over wholly, unreservedly to the wild pleasures of Whitehead’s Harlem Trilogy: first Harlem Shuffle, now Crook Manifesto, and a third novel still to come.

In the new installment, Whitehead returns to the misadventures of Ray Carney, quickly ascending to the status of éminence grise in the small business community of 1970s Harlem, but with that crooked side of his still lurking. Here, the catalyst for his explorations of the city’s dark heart is something simple: his daughter really, really wants to see the Jackson 5 at Madison Square Garden. That’s where Carney’s passage back over to the criminal world begins. Along the way we’re thrown in with a cast of schemers and operators, together making up the fabric of a shadow society. Whitehead writes the city of that era with such assurance, we begin to catch glimpses of the profound, pulsing whole: of New York in its most essential, corruptible form.

Whitehead says he’s taken on this project because it’s fun. Because it gives him pleasure to write. From that simple impulse, he’s building something to last generations. I was lucky enough to catch up with him in the lead-up to the new book’s publication. We talked about New York, Blaxploitation cinema, Sidney Lumet, and a kid’s game that is anything but.

Dwyer Murphy: Can we start with ringolevio, the kid’s game? It’s a big part of this book. Are you an aficionado?

Colson Whitehead: I played it in Long Island. It wasn’t quite as extravagant and wide-ranging as the version in this book.

Dwyer Murphy: In Massachusetts we played a version called manhunt. But I gather ringolevio, the classic form, is famous as a New York City street game.

Colson Whitehead: I’ve never played in New York.

Dwyer Murphy: Me, neither. It sounds great. Are your kids into this?

Colson Whitehead: I haven’t heard the word spoken out loud before I started writing the book.

Dwyer Murphy: As a thematic tool, it operates a little like the idea of dorveille, the second sleep, in Harlem Shuffle. It manages to tie a lot of stories together. Can you tell me a little about how you threaded it in?

Colson Whitehead: There’s a notion involved: of people playing at gangsters, playing at being criminals. playing at being on the right or wrong side of the law. I took that little nugget and tried to make it work for Carney and Munson. In a way, Carney is on the outside looking in at the criminal life. He’s a bit of an imposter, though he understands the proper criminal codes. And then the actors in the Blaxploitation section are of course civilians pretending to be criminals.

So ringolevio, it’s this kid’s game, but as you get older, the stakes get higher. In the first book, Freddie and Carney were, as kids, engaged in sort of low-level mischief: stealing comic books and candy. Then as they get older, the stakes get higher. That’s what Munson, too, is ruminating on: where did it all start and what does it mean now?

Dwyer Murphy: We spoke a few years ago and you mentioned off-hand you had a crime fiction project going. Now, two books later, with another still to come, this is going to end up the biggest project you’ve ever taken on. You’ve committed a big chunk of your professional life to it. Why?

Colson Whitehead: Because I like it. No other reason. I like it, so I’m doing it.

Usually when I finish a book, I’m really tired of it. But after Harlem Shuffle, it was the first time I had a character and a world I wanted to pursue for years and years. You know, I wondered if I’d be sick of it, but I’m not sick of it yet. When Harlem Shuffle came out, I was in the middle of Crook Manifesto. I didn’t mention the word trilogy out loud, because what if I got bored? What if I didn’t want to do it? But now, it’s fun and it’s rewarding. I should be writing the books that give me joy and keep me interested, otherwise it’s not worth pursuing.

Dwyer Murphy: Is there a special mindset required when you’re writing inside Carney’s world? Do you see everything crooked? Are you walking around seeing the world in terms of its corruption?

Colson Whitehead: Well you always have to get into character: that philosophical palate and mood. So, if I’m on the highway, I might think, oh that’s a good place to dump a body, but I did that before, too. At this point, I’m used to turning it on and turning it off.

I’m not reading a lot of fiction these days. I’m reading New York stories, and a lot of nonfiction. That takes up my outside, non-work time.

Dwyer Murphy: What kind of nonfiction?

Colson Whitehead: Well, I was getting a little sick of reading memoirs of criminals and straight, broad histories of New York, so I picked up David Hajdu’s book about the early folk scene, Positively 4th Street, about the early days of Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. And of course, now that I think about it, it was a New York book. It’s about New York in the late 50s early 60s and people coming and remaking themselves and trying to find themselves, so it overlaps with the concerns of the Carney story, the Harlem trilogy. Even if it’s not purposeful research, I seem to end up back in New York.

Dwyer Murphy: How about for the Blaxploitation section of the book—was there any special research involved? I take it that culture is an interest of yours.

Colson Whitehead: I love exploitation pictures. Growing up in the 70s and 80s I saw all those Blaxploitation pictures when I was young. There weren’t a lot of movies with predominantly Black casts when I was growing up, so I gravitated toward them. Then I started out as a critic in my twenties, and when I began writing my early fiction, it was very pop culture oriented, and there’s a lot of Blaxploitation stuff and about Black imagery and pop culture in there. It was interesting coming back to that material in my fifties, trying to figure out how it would serve Carney.

Going back to what we were saying about ringolevio—ringolevio is a game where you’re jailing the malcontents and criminals, and there are jail breaks. Blaxploitation is a sometimes cartoonish enactment of lawlessness and criminal activity, so I was thinking about how to play with that while writing a crime novel. I think Pepper says something about how the film crew in the book was playing at being bad, and then something bad came and nipped them in the bud. So Blaxploitation let me talk about playing at criminality, and what happens when reality intrudes on our games.

Dwyer Murphy: Did you know Zippo was coming back in the second book in such a prominent way? I’m asking in part because I wonder about how you plan these things out over the course of multiple books.

Colson Whitehead: When I finished the first book and started planning the second book, I realized Zippo would be an anchor. Harlem Shuffle was in copy edits then, so I had time to foreshadow a little bit. I think he mentions wanting to be a director at some point. I’m a big planner. When I committed to a trilogy, I tried to figure out what was going to happen in the third book so that I could seed it into the second book. Some people make up their stories as they go along, but I need an outline. And when it’s a trilogy, I think it really helps to know some of the big beats and the ending.

Dwyer Murphy: And with Zippo, the idea of arson returns. That’s another notion that’s doing a lot of work in this book. This stuff comes up in all three parts of Crook Manifesto: arson, fires, burning buildings.

Colson Whitehead: Well, it was a big part of New York history at that time, especially in poor communities: the Bronx, parts of Harlem. So I knew that was going to be the heart of the third story. It becomes more immediate as the book goes on. In the first section, in 1971, there are a lot of sirens, smoke in the distance, fires seen in passing. In the second section, there’s a more immediate fire. And in the third section, arson plays a much bigger role. If I know that when I’m starting the book, I know I can lace it into the first section and it’ll pay off later in the book.

Dwyer Murphy: Speaking of the characters, I wasn’t expecting Pepper to get a little P.I. novel in there.

Colson Whitehead: He was so fun in the first book, I thought he should get his own caper. Carney and Pepper, they’re both outsiders. Carney is an outsider in the criminal world. Pepper is an outsider in the normal world. He’s kind of a sociopathic freak who can’t understand normal family relationships. And in the same way Pepper brings Carney into a better understanding of the criminal world, Carney brings Pepper into an understanding of what it means to be a normal human with a family. It’s a big canvas, so there’s room for Carney to drop out and we can see the world through Pepper’s eyes. Then we come back in the third section and have a bit of synthesis.

Dwyer Murphy: It reminded me a little of those big 19th century city novels, something from say Balzac, where you know these characters from other books, other stories, and finally they converge. It’s a special literary thrill, when that happens, and kind of a throwback.

Colson Whitehead: I’m glad. It was fun for me, too. They’re both characters I have a lot of affection for. It was fun for me to have characters I like so much.

Dwyer Murphy: What about a character you don’t like? I’m assuming Munson, your crooked vice cop, might come under that category.

Colson Whitehead: No, I love Munson.

Dwyer Murphy: He’s a demon out of a Sidney Lumet movie.

Colson Whitehead: He is, and of course Serpico was my first introduction to the Knapp Commission and police corruption in the 70s. I didn’t watch Serpico again, I’d seen it enough. I went back to the nonfiction book, the one Peter Mass wrote about him. And the actual Knapp Commission report. It was cool to go to the real-life source after first encountering all this through Sidney Lumet. And Lumet looms large for me as a child of the 70s, whether it’s Serpico or Dog Day Afternoon or Network. He’s someone who introduced to me this institutional corruption: in the FBI, in the police force, in network television.

Dwyer Murphy: I just went back to Prince of the City recently. I hadn’t thought about that one in a long time.

Colson Whitehead: As a kid, I remember loving Treat Williams because of Hair: The Musical. We were a big Treat Williams house.

Dwyer Murphy: So, you’re definitely committed to doing another book? That’s set? You’re saying the word trilogy out loud now?

Colson Whitehead: Yeah, it’s a trilogy. A lot of the third book is planned. Not necessarily the names of characters or what cigarettes they smoke, but the big stuff.