Have you ever picked up a book, turned on a show, opened an app, booted up a game, and then an hour or two later found yourself wondering where the time went?

That’s a good thing, right? You were drawn in, compelled to continue; that’s the mark of a powerful experience.

But what if whatever you were reading, watching, scrolling, or playing wasn’t just hoping to hook your attention—what if it had been methodically designed to monopolize your focus until it consumed you, forever altering your point of view?

In a world driven by concepts of engagement and algorithms operating off personal data, that premise isn’t so far-fetched. The precision targeting of visuals and ideas that make us happy, sad, or angry seems to reach newer and more frighteningly sophisticated heights all of the time.

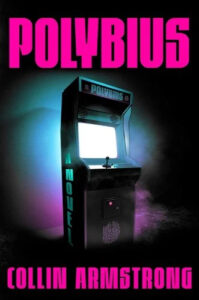

The classic urban legend at the center of my book Polybius—a mysterious arcade game infecting players’ minds, causing them to lose time, driving them to violent action against themselves and others – predates modern ideas of behavioral and psychological modification via screens by decades, whether you’re talking about when the legend is set or when it entered public discourse. But the parallels are obvious, and they exerted a lot of influence—in retrospect some conscious, some not—in how I imagined the legend’s origin and tried tethering it to reality.

Like any good urban legend, there’s an uneven mix of truth, conjecture, conspiracy, and imagination at the center of the “real” Polybius. What follows is a short primer on the legend itself, along with thoughts on where it might’ve come from and how I adapted and added to it, in writing my book.

THE LEGEND

The story goes that, in the early 1980s a striking, visually advanced game called Polybius showed up in a handful arcades in the Pacific Northwest. Developed by a previously unknown company called Sinneslöchen, the game’s frequently been described as a “tube shooter” similar to Tempest, where you pilot a craft around the edges of a never-ending vortex, blasting enemy ships blocking your path. It was popular – some might say addictive; kids lined up for hours to play, and some began to exhibit strange behaviors after. They were aggressive, depressed, disassociated; some suffered seizures, at least one committed an act of self-harm.

In some tellings, the Polybius cabinet disappeared as quickly and mysteriously as it had arrived. In others, men-in-black types were known to show up and transfer data from the game to a drive they carried—to what end was unknown, and the game eventually vanished from those locations, too.

By the late ‘90s or possibly very early ‘00s, an entry for Polybius—which included many of the details mentioned above—was added to the website Coinop.org, a no-frills database of information on arcade games. This is believed by many to be the first mention of the core story of the Polybius legend online.

In 2003, Gamepro Magazine featured Polybius in an online article entitled “Secrets and Lies,” that explored video game-related myths and rumors. It was the first mainstream mention of the legend. After, the trail grows too diffuse to follow but the idea of Polybius was out there and began spreading into other media.

There have been articles, videos, other books, podcasts, TV shows, video games, and no doubt feature film scripts (elements of my book started life in the ‘10s as a feature pitch) dealing with the legend. Interestingly, though, none have altered the core story; for the most part, it’s remained intact, just tantalizingly unclear enough that you might be willing to believe the game existed.

WHERE THE TRUTH LIES

Of course, we’re talking about an urban legend, so it won’t surprise you to hear that none of that core story has ever been corroborated. There are people who claim to have ROMs (playable software) of the game; people who claim to have been there in the ‘80s and to have seen the game in person; people who claim to have cabinets in storage. The Coinop.org entry suggests that either a ROM or cabinet (it isn’t clear which) might have made its way to Kyiv, Ukraine, of all places.

There’s just nothing out there backing any of these claims up.

It’s been said that urban legends grow out of fear over changes in culture, and when you look at Polybius in that context, it starts making a lot of unexpected sense. Let’s take the era of the legend itself first, the early 1980s.

It was the golden age of the arcade, with thousands of independently owned and operated locations and millions of cabinets. People were spending billions on games in the early ‘80s, not adjusted for inflation, and it was a young industry—video games hadn’t been around very long and were becoming widely accessible. Politicians, members of the media, and parents saw kids spending a fortune and zoning out in front of screens for hours in a way they hadn’t before. This was a new, strange phenomena, and concerns over the psychological effects of gaming on kids’ minds—Do violent games make violent people?—were already being voiced.

Couple that general unease and paranoia with some specifics that closely mirror aspects of the Polybius story, and more pieces start falling into place.

In 2013, a writer for the website Skeptoid named Brian Dunning dug deep and uncovered ‘80s-era reports in Portland-area papers—where the legend is often centered—about kids passing out from exhaustion after marathon sessions at local arcades. In addition, law enforcement raided a handful of arcades in the area for illegal gambling operations. And nationwide, there were reports about photosensitive epileptics suffering seizures while playing.

So now we have paranoia over new technology, kids suffering physical side effects from playing, and police and federal agents lurking in the shadows.

When it comes to the question of whether there was a real-life cabinet that could’ve been mistaken for Polybius, a writer named Patrick Kellogg makes a compelling case for a game called Cube Quest. It was full of trippy visuals, unorthodox sound design and gameplay, and ran off of a laser disc, similar to games like Dragon’s Lair and Space Ace. Disc-based games were known for breaking down, so it’s possible repair techs could’ve been seen probing cabinets like the ones that housed Cube Quest with arcane-looking tools.

I’ve always been partial to the idea that Polybius was really Tempest, a visually intense tube shooter long associated with rumors of giving players seizures and hallucinations. In either case, even in the case of other games like Gyruss, there were games that hewed close to how the visuals in Polybius have generally been described.

Take these details, mix in the passage of time along with an early pop culture explorations of games crossing over into the real world—Tron, The Last Starfighter, “The Bishop of Battle” segment in the horror anthology Nightmares, Robert Maxxe’s book Arcade—and it’s easy to see how someone with an overactive imagination could’ve conjured the idea of a killer arcade game.

If you jump ahead to the late ‘90s / early ‘00s, when the legend started making cultural in-roads, there’s even more evidence to ground it in the real world.

It was another moment of change for the gaming industry, which remained a lightening rod for a very loud subset of politicians and parental advocates. Games were growing more sophisticated in terms of visuals and content, and gameplay was moving online, connecting people around the globe in a way that seemed impossible just a few years prior.

Once again, change was afoot, and the same old paranoia about the effects of gaming was bubbling.

What’s more, it was now possible to share foggy memories online. Someone across the country or around the world could read your words and think, “Huh, yeah, I kind of remember some kid passing out in arcade, too.” They add their recollection to your story, which someone else then picks up, on and on, over and over, like an unintentional exquisite corpse.

The building blocks for the story were in place, and a method for spreading it far and wide was ascendant. Polybius’s fate as part of the urban legend canon was, it seems, sealed.

Of course, it’s also possible that there really was an evil cabinet of doom wreaking havoc across Portland in the early ‘80s, too. One can dream, at least.

IRL

If you poke at an urban legend too long, you’re liable to let the air out of it. This probably explains why – aside from vague overtures to men in black and psi-ops, military lingo for psychological operations that aim to destabilize through mind games instead of violence – no one appears to have ever seriously asked why Polybius was made. Or how. Or even by whom.

Answers to those questions have never been offered because, in all likelihood, they don’t exist.

For my purposes, though, I wanted answers, even if I didn’t intend to include them all. Among a handful of big picture ideas I had for the book early on was to treat it like an origin story for the legend. Where did this core story come from? How were other key details swept away or covered up? Who would’ve been capable of building something so sophisticated in the early ‘80s? While I wanted to stay true to the core story, I knew I’d need to find my own path.

Governments the world over have engaged in psychological warfare for centuries. From fake battle plans leaked to the enemy, to inflatable battalions that fooled surveillance details, to recordings of ghostly voices meant to spook opposing soldiers, some truly outré ideas have been deployed in the quest for victory. It doesn’t feel like too big a leap, then, to think that something as innocuous as a video game could’ve been considered as a vector for a psi-op.

Part of the decision behind where I set the story, in a small town in Sonoma County, California that’s being transformed into a suburb of a then-burgeoning Silicon Valley, was proximity to the world hub of technological innovation. Who knows what’s trapped on a hard drive, or sitting on a dusty shelf in a warehouse somewhere around San Jose or Palo Alto that wouldn’t do us all in if it ever escaped?

At the risk of veering too far into spoiler territory, I think all that’s left to say here is that powerful institutions and individuals act all the time without much thought given to any downline effects. Existentially frightening ideas are introduced then brushed aside or forgotten… but they aren’t necessarily gone.

In a world where it’s increasingly hard to trust that the things we’re being shown aren’t meant to harm us, why couldn’t Polybius have existed as a prototypal rage-bait generator lighting a fire under our worst instincts? We’re being haunted day and night by what we see on our screens, driven to shout in all caps at strangers who may not even be real, via technologies we naïvely invited into our lives.

If urban legends really are a reaction to the times, then I’m hard-pressed to think of another that has more to say about our ever-deepening relationship with technology than Polybius. Like the best urban legends, it has something to say – hopefully, you’ll find something for yourself in the book, too.

***