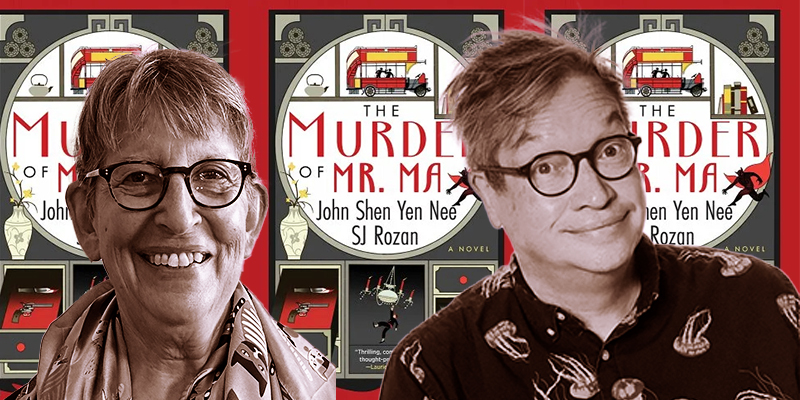

SJ Rozan is the bestselling author of twenty novels and over eighty short stories, and editor of three anthologies. Her multiple awards include the Edgar, Shamus, Anthony, Nero, Macavity; Japanese Maltese Falcon; and the Private Eye Writers of America Lifetime Achievement Award. She’s served on the national boards of Mystery Writers of America and Sisters in Crime, and as president of Private Eye Writers of America. She was born in the Bronx and lives in Manhattan.

John Shen Yen Nee is a half Chinese, half Scottish American media executive, producer and entrepreneur who was born in Knoxville, grew up in San Diego, and is now based in Los Angeles, with a penchant for very long run-on sentences. He has served as president of WildStorm Productions; senior vice president of DC Comics; publisher of Marvel Comics; CEO of Cryptozoic Entertainment; and cofounder of CCG Labs.

Nee & Rozan are most recently the co-authors of a swashbuckling series opener called The Murder of Mr. Ma (Soho Crime, April 2024). Their collaborative novel introduces a Holmes and Watson inspired dynamic duo consisting of two semi-fictionalized Chinese historical figures—Judge Dee Ren Jie from the 7th century, whose valorous spirit has been mythologized in countless stories, and the 20th century academic and novelist Lao She—who work together (if reluctantly, at first) to track down a serial killer targeting Chinese immigrants in post-WWI London. They were kind enough to set down some questions and answers for CrimeReads about the cowriting & research process, why they chose to base their protagonists off real historical figures, and how they plan on introducing more elements of Chinese culture and history to readers as the series continues.

—

SJ Rozan: The idea for this series was yours. You I started working together in the summer of 2020, during the pandemic. How did you find me?

John Shen Yen Nee: Via Alex Segura, who introduced me to Josh Getzler at HG Literary. I told Josh about the project and he said, “I have the perfect writer. SJ Rozan has been writing the Lydia Chin and Bill Smith series, and she knows how to write Asian people very well.”

Rozan: “The perfect writer.” Exactly what one hopes one’s agent will say. That’s kind of what he said to me—that he’d talked to “this guy John Nee” from the comics world—you were publisher at Marvel Comics at the time—and that you had a project that would be perfect for me.

Nee: All credit to Josh Getzler for recognizing perfection.

Rozan: Josh gave you my number, and you called me. From the beginning I was captivated by your imagination and your vast historical knowledge. As I recall we talked for an hour and a half. I didn’t really understand the through-line of the project until I read the outline for the first book, though. That was also vast. But I loved it, especially the relationship you were positing between Dee and Lao. And the kung fu.

Nee: There’s a strong martial arts tradition in Chinese hero stories.

Rozan: I was glad to see you wanted that in these books because I adore the early Hong Kong kung fu movies. We had to find a kung fu consultant for the choreography, though.

Nee: Sifu (Master) Paul Koh. His sensibility turned out to be perfect.

Rozan: So much perfection involved in this project, it’s amazing. The other thing I loved was that, after I read the outline and I suggested to you that it needed some serious trimming, you said, “Okay, this and this and this are important to me; everything else is negotiable.” That’s how I knew we could work together.

Nee: The process, from my point of view, was like butter. We did talk about some significant changes, because the original outline had some very dark tones that you felt didn’t serve the story.

Rozan: For the record, dear reader, John can be pretty dark.

Nee: We agreed on some fundamental changes, and then you went to town. There was very little to change in the finished pages. I know that you self-edit quite a lot, so most of the work coming back to me was ready to print. Is that the way your previous co-writing project went?

Rozan: The method was the same, though the process was maybe a little less buttery. You’re talking about the books I wrote with Carlos Dews, two paranormal suspense novels that were published under the pseudonym Sam Cabot. (Note: these are Blood of the Lamb and Skin of the Wolf.) Carlos also came to me with a story he’d been thinking about for some time, and an elaborate outline for the first book. In the same way as you and I work—and here it occurs to me readers may not know how you and I work—he provided the story, I trimmed or fleshed out the outline where it needed it, and I did the writing, sending it to Carlos for editing as I do with you. Let me take this opportunity to say, by the way, that I’m not an outliner. I’ve tried it and I never will be, I just can’t, the same way I can’t throw a baseball. But to have an outline dropped in your lap—whee! I never had such fun as writing The Murder of Mr. Ma.

And now, let me ask you: Judge Dee Ren Jie is an actual Chinese historical figure, but he lived during the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century. Western readers probably know him, if at all, through the Robert Van Gulik translations and stories. What made you think he’d be a good hero for the 20th century?

Nee: I’d always wanted to use him in some way. Bringing him into 1924 was inspired by the BBC “Sherlock” series, when they had Holmes and Watson in modern times. But then they included an episode in the original Victorian time period, and I realized you can time jump these guys.

Rozan: Are we going to time jump Dee and Lao back to the Tang Dynasty?

Nee: Would you like to?

Rozan: No. I think we can just keep them moving forward, that’ll be fine. But we’re not just telling adventure stories here, are we? You consider it important to include elements of Chinese culture and history in this book and the series as it goes on, right? Why?

Nee: I think that there’s very little understanding of China’s history in the West in general. What I was hoping to do is to create an entertaining platform where we could touch upon ideas that are important to Chinese people. Subjects like the Taiping Rebellion, the Treaty of Versailles, and the Opium Wars.

Rozan: And food.

Nee: Of course, food. You wouldn’t let me have the darkness, I had to have the food porn.

Rozan: Luckily I’m also a fan of food porn. Possibly because I don’t cook.

Nee: I do. When you come out here I’ll cook you a Chinese banquet.

Rozan: You’re on. You said “out here”—I think we should tell the readers that I’m in NYC and you’re in LA. We didn’t meet until almost two years into the process.

Nee: And your first words to me were, “No one told me you were so tall.”

Rozan: Well, no one had.

Nee: And no one told me you—

Rozan: Let’s go back to the book. Besides the food and the kung fu, what do you want readers to take away from this series?

Nee: What’s important to me is to tell the history of China from the early 1920s through the Xi’an Incident in 1936. I want to really explain how we got there, and so, how we got here.

Rozan: The Xi’an Incident—the kidnapping of Chiang Kai Shek by two of his own generals.

Nee: Yes. A political kidnapping, with a specific motive. Little known anymore in the West, but still tremendously important to the Chinese people.

Rozan: Therefore important to Dee and Lao.

Nee: When we get up to it, yes. But I never want to lose track of the fact that we’re writing crime novels with historical backgrounds, not history books.

Rozan: Don’t worry, with me as your co-writer, you won’t. Though as I said, from the beginning I was amazed by your breadth of knowledge. Because I’ve always been interested in China I’ve amassed, over the years, probably more knowledge about China than most Americans, and yet you kept coming up with things I’d never heard of or was only vaguely acquainted with. Lao She, for one.

Nee: I really want everyone to appreciate that Lao She was an author who was revered, and then purged, and now re-revered. I wanted to tell his story so people would be able to reconnect with his works, and in 1924, he happened to be a visiting scholar in London. It fit in so beautifully.

Rozan: You sent me all kinds of books to bring me up to speed, including a couple by Lao She. I’d heard of him but never read him. I was surprised to find out what high esteem he was held in by Western critics at the time, besides being revered, as you say, in China. It’s easy to see why: the guy could be touching, discursive, and flat-out hilarious. You also sent books about the Chinese Labour Corps in France during WWI, which becomes an engine to drive the story in The Murder of Mr. Ma. I’d never heard of it before.

Nee: Like most Westerners. But 160,000 Chinese laborers in France, close to or at the front lines, digging the trenches, building the barracks, repairing the trucks—it’s a story that really should be told. I also wanted to illuminate, without being didactic, the anti-Chinese prejudice in England in those years.

Rozan: That was something I did know about. It was the time of the Yellow Peril, as much in England as in the US. Chinese goods—porcelains, silks, jades—were in great demand but Chinese people were seen as irrevocably and frighteningly Other. The Mysterious East—“mysterious” was one of the more benign words used about Asians.

Nee: Insidious, inscrutable, degenerate—Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu was one of the earliest but there were a lot of other evil cunning Chinese villains. Also, this was the time opium addiction was getting to be a problem in England. In spite of the historical fact of Great Britain forcing China to open its ports to British opium-carrying ships, when it boomeranged back to England it was labeled a Chinese vice.

Rozan: You can see some of that in Lao She’s Mr. Ma and Son—

Nee: —the book that our book is the backstory to.

Rozan: Uh-huh. You can see some of that prejudice in the way the landlady at first is worried the Mas smoke opium and eat rats. Also in the way the street children call Mr. Ma names, and in the disdain the jeweler, for example, has for him. And of course in the romances, his and his son’s, which both are hopeless because they’re Chinese men hoping for the love of white women.

Nee: But putting aside Chinese history, tell me: when we started how versed were you in the setting of this book—London, 1924?

Rozan: Not very. I’d read my Virginia Wolff and some other writers of the period—and my Laurie King—and over the years had acquired some idea of the art, the music, what the roaring twenties were about in Great Britain vs. here. That was about it. Once I committed to the project I began reading, in addition to the books you sent, a whole bunch of books written by Brits in the ’20s, mostly for setting and also for language, both the rhythm and the vocabulary. Luckily there are movies, some made at the time and some contemporary and carefully researched, which were useful to me for the clothes, the cars, and the house furnishings. Some TV shows, too. And I cannot recommend old mail-order catalogs highly enough, if you’re doing historical research. As a former architect, also, I was aware that Modernism was just then finding its place in architecture and the arts. That informed my vision of setting, though maybe more in the second book in the series than this one.

Nee: I know you don’t like to write about a place you haven’t been to. You told me you’d been to London but not for years. Do you feel like working during the pandemic was a problem, that the writing would have gone more smoothly if you’d been able to travel there?

Rozan: At first I did, but it was pointed out to me that so much of what was there in 1924 is gone now anyway; actually gone, either bombed during the Blitz or redeveloped out of existence; or still there but so changed, and its surrounding context also so changed, that there would be nothing to be gained by visiting it. I had to rely on the historical sources I had, and my imagination. Luckily I’d been in the same situation once or twice before (The Shanghai Moon, Paper Son) so those muscles had been exercised.

Nee: You mentioned our second book in the series, which is finished and due out next year. Are you going to stick with me as Dee and Lao go on, or am I going to have to find another writer?

Rozan: If you did that I’d have to kill you.

***