I’ve read hundreds of mysteries, thrillers, and novels of suspense over my lifetime—and I’m still going strong.

At one stage, I worked in a library. At another, I worked in a remote town in rural Japan. Why are these things relevant? Both experiences widened my reading tastes.

At the library, books just kept coming across my desk, and in Japan (prior to the advent of e-books), because I wasn’t fluent enough in written Japanese to read novels, I read whatever English novels I could get my hands on.

That is to say, I’m an omnivorous reader—and in the “crime reads” genre, that means I’ll read anything from a cozy mystery set in an adorable little town, to the darkest of dark Scandinavian noir. This has left me with both an admiration for the depth and scope of the genre, and an understanding of what it takes to be a character in different types of suspense.

First, we have what I affectionately term the nosy parker. He or she (though most often she) is a familiar and beloved protagonist in cozy mysteries. Because she isn’t a cop or otherwise part of the official investigative machinery, the only way she can solve a crime is to poke her nose into everyone’s business—and sometimes, into dangerous territory.

This is the one subgenre of mystery where I’m not screaming at the protagonist to not go down into the dim, unlit basement while a murderer is on the loose. As a reader of cozy mysteries, I’m well aware that such errors in judgment are part and parcel of the character archetype. I might shake my head, but I’m going to read on in the full knowledge that in a cozy, while the main character might end up with a bruise or get a bit roughed up, she will survive.

One of my favorite cozy mystery series is Vivien Chien’s Noodle Shop series. I love Lana Lee, manager of her family’s noodle restaurant, and amateur sleuth who simply cannot help herself—but I would never ever invite Lana to my house. Because just like Jessica Fletcher of Murder, She Wrote, where Lana Lee goes, a dead body is sure to follow.

That, too, is one of the unwritten rules of being a cozy mystery protagonist.

Then we have the detectives, beat cops, and lawyers who populate the pages of the novels I’m going to put into the general “procedural” category—these are all characters who are part of the official investigative machinery, so they’re in the inner circle.

This is a fascinating area for protagonists because they really do run the gamut. The traditional archetype is the brilliant but beaten-down older (and most often, male) detective who probably has a drinking problem and a terrible relationship with his family—if he isn’t a closed-off and emotionally tormented island of a man.

These types of protagonists bring the weight of their years and experiences with them, and those color all their interactions—and quite often, they drive the decisions the characters make along the way.

Michael Connelly’s iconic Harry Bosch is driven to find justice for victims due to his own traumatic childhood (including the murder of his mother and his life in foster homes and on the street). He’s imperfect and a little broken, and a character we forgive for his mistakes because we understand why he makes them.

Jo Nesbø’s Harry Hole is a detective in the same vein – perhaps even darker, though that may be the Scandinavian noir element coming out.

But not all procedural protagonists are dark and grim.

One duo I find fascinating is Alex Delaware (child psychologist) and Lieutenant Milo Sturgis from author Jonathan Kellerman. Alex is the one with the messed-up childhood, while Milo is an openly gay detective (the series begins at a time when that was simply unacceptable). Milo is in a stable relationship and eats and drinks with the fervor of a gourmand, while Alex has a darker strain to his emotions.

Together, they create a crime-solving duo that is neither too dark nor too light.

I feel that Anne Cleeves’ Detective Vera Stanhope, too, straddles this line. She has the difficult backstory (her father was a poacher, raised her in a remote and wild location, and wasn’t particularly good at that raising). She’s gruff and can offend people with her bluntness, but at the same time, she has a deep core of kindness that makes us want to follow her as she solves crime.

A complex and deep backstory is necessary for the leads in these types of procedurals—because at the heart of it, they are as much the story as the mysteries they solve. We want our broken, complicated heroes to find some surcease.

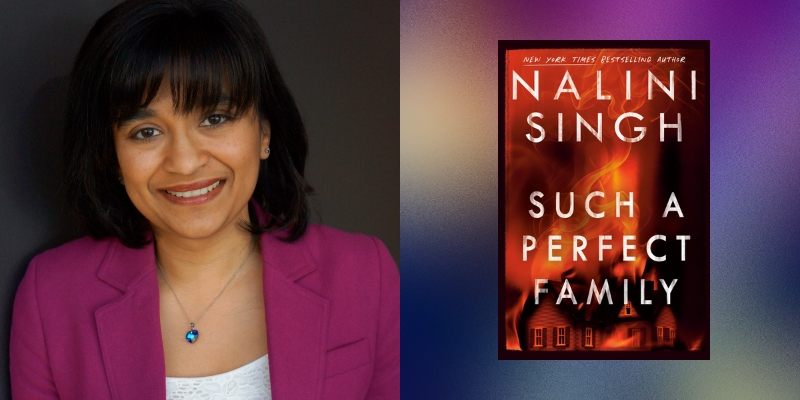

The final subgenre I want to focus on here are domestic thrillers (in the broadest possible sense). This is the closest to my heart because it’s what I write—but of course, I’ve read plenty, too.

So I can tell you that the protagonists in domestic thrillers all have secrets. Whether it’s the husband with a mysterious and hauntingly perfect late wife (Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca), the woman with multiple personalities inside her (Alyssa Cole’s One of Us Knows), or a group of friends who all did something bad once upon a time (Donna Tartt’s The Secret History*).

It’s in domestic thrillers that we most often find the unreliable narrator – because again, it’s all about secrets. Who better to keep the secret than the person we’re trusting to lead us through the labyrinth?

The secrets, of course, are as varied as the specific protagonists. But this subgenre, for the most part, leans into the murkiest shadows. The secrets tend to be dark, emotionally complex, and often murderous.

Unlike with our procedural leads, we might not always like the leads in domestic thrillers, but we’re compelled by them. We go on this journey with them because we must in order to find the answer…never knowing what lies behind the door or if we can trust our guide.

Of course, these are far from the only subgenres of suspense. Any number of books fall in between subgenres, or consciously stand halfway. I starred The Secret History above because it’s not usually shelved in domestic thrillers. Rather, it’s seen by many as a defining text of the dark academia genre—and yet, I’d argue that it’s also very much about people and relationships and a terrible, awful secret.

The suspense field is as vast as our imagination—and the same goes for the personalities and pasts of the protagonists who people them. Because despite the surface commonalities I’ve noted, all the characters I’ve mentioned are very much individuals, with journeys all their own.

For that, and for the breadth of the genre as a whole, this reader can only be grateful—because no matter if I want to walk in the light or venture into the shadows, there will always be a book—and a protagonist—that suits.

***