I was a parent of young kids during the years when the Marvel superhero films dominated movie theaters. One movie after another, super soldiers and sorcerers, Norse gods and mecha-warriors—a battalion of avenging champions, extraordinary beings with powers beyond what any mere human could aspire to. They weren’t perfect, of course; they had their regrets and dark moments and fatal flaws. But let’s face it: if you can rescue a bus full of kids by shooting spider silk from your wrist, see the future with a spin of an eye-shaped glowy green medallion, or literally carry a marooned spaceship back to earth, I suspect that might compensate a little for the hardships.

I enjoyed those movies, with their action sequences, their triumphant music, and soul-searching climaxes; no one ever had to drag me to the theater. But I never, not once, saw myself in those heroes.

My life is pretty ordinary, all things considered. I’m a middle-aged woman who gets out of breath climbing stairs. I work too many part-time jobs and watch too much Netflix. I wear unfashionable second-hand clothes. I have giant feet. I live in the suburbs. There is nothing heroic about me. And I’m genuinely okay with that.

I think this may be related to my love for amateur-sleuth mysteries. Even before I started writing them, I read these books voraciously. In this corner of the mystery genre, the sleuth has no special powers; these heroes are ordinary people, living ordinary lives, who find themselves thrust into a situation they never anticipated. Maybe someone they care about is in danger, or unjustly accused; perhaps someone’s life has been tragically taken and the authorities aren’t very interested in finding out who is responsible.

These ordinary heroes take whatever resources and skills they have, step up, and solve the crime. And then, in the next book, they do it again. They do it without superpowers; most don’t even have access to the resources used by professional law enforcement. But I would submit that they have particular areas of expertise, and that these are fairly consistent from one amateur sleuth to the next. Ordinary skills, unremarkable on the surface, on which these characters draw to bring the guilty to justice.

I would submit that many of us who read their stories possess many of these same tools. Would we know how to use them if we woke up one day with our lives taking the path of an amateur sleuth in a mystery novel? Would we recognize the tools in our own toolbox?

Community Roots

This tool belongs to people deeply embedded in their communities, the ones who know everybody. The high school administrative staff. The parish pastor. The owner of the cafe, where half the town buys its coffee and croissants on the way to work. The bartender at “the” neighborhood pub. The Mom Network, be it Little League, or Scouts, or the fifth grade. Some are “people persons” who thrive on interaction with their web of friends and neighbors—who know not only everyone’s names but also how many kids they have, what activities they are involved in, and the names of their pets. Others may be more inward, quietly present—watchers and listeners who often know more about their little world’s business than anyone realizes.

Access to information

Information is power. In our current moment in time, as we watch our search engines degrade beneath the drive for advertising revenue and the flood of sponsored search results, the skill of finding targeted and usable information holds great value.

No one embodies this value more than librarians, in my opinion. Not only do their institutions often provide access to a broad swath of subscription databases and other information sources, but those who work with them are trained to access and apply that information. Researchers of all stripes—academics, genealogists, archivists, and so on—fall into this category. And don’t underestimate the information-gathering skills of the office manager, the HR employee, or the accountant.

Observational skills

Humans are, I believe, instinctively inclined to notice departures from the normal patterns of daily life. Some only pick up on large shifts, whereas others are attuned to the smallest fluctuations. Some are visually oriented, noticing shifts in presence or body language; some take in surrounding conversations without even thinking about it. Everyone’s mind works a little differently, but the beauty of this skill set is that mindfulness and awareness can be cultivated and practiced.

Powers of (social) invisibility

Are you unremarkable in appearance, forgettable in a crowd? Do you work at a job where you are expected at all times to fade into the background and not be noticed? Are you a teenager, perpetually overlooked by adults, or an older adult, perpetually overlooked by, well, everyone?

The value of being unnoticed and underestimated is often overlooked in our superhero-seeking world, where so many influences clamor for our attention and gaze. Just ask the unassuming Miss Marple, or Nita Prose’s Molly the Maid, or any member of Richard Osman’s Thursday Murder Club. Each of these wields their society-imposed obscurity like a finely tuned instrument; in their anonymity, they create a space to take in new information and see patterns form.

Improv skills

How quickly can you make up an excuse to be somewhere you are not? How effortlessly can you convince a complete stranger that you might have shared a long conversation years ago? Can you talk your way into a building or room where you probably shouldn’t be? (Note: Be careful with this one; do nothing that would get you in trouble with law enforcement!)

Calm in a crisis

When things go sideways, are you the person who explodes with anxiety and panic, or do you remain calmly clinical, able to reason your way out of disaster? This, especially when combined with the improv skills mentioned above, can be a valuable ability; when everyone else in your environment is losing their cool, if you can keep yours, you’ll have a major advantage.

Special skills

Then there are the more unique tools, the ones not everyone can pull off, but which can be incredibly effective in a pinch. This is where we find amateur sleuths like herbalist and medieval medic Brother Cadfael from Ellis Peters’ classic series and illusionist Tempest Raj from Gigi Pandian’s Secret Staircase mysteries; their special abilities won’t solve every murder, but they might be exactly what’s needed for this one. The architect who can find the secret room, the psychologist who recognizes an inconsistency in the testimony of a patient, the botanist who identifies an unlikely plant near where the body was found—the list is endless.

What if my toolbox is light?

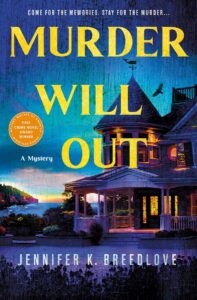

If you don’t believe you possess enough of these tools on your own to feel comfortable imagining yourself solving a case, you can do what amateur sleuths have done all the way back to the early days of the genre: put together a group and work together, balancing different abilities and innate talents, to cover as many bases as possible. In my Murder Will Out, the protagonist is supported by several fellow crime-solvers: the tech-savvy village librarian, the gregarious island innkeeper, and the local cafe owner (who happens to also be an antique dealer and former attorney); my sleuth might be a seemingly unremarkable watch-from-the-edges person herself, but she is surrounded by friends who hit the places where she is weakest.

It’s all just fiction, though. Right?

Of course, fiction is fiction, and of course, most of us will never find ourselves in the situations our amateur sleuths do again and again. But the best of these mysteries offer us as readers both a mirror and a window: they invite us to open ourselves, to see and notice our corner of the world, suggesting that, perhaps, if we keep our eyes open and respond to the calls to adventure in our own lives, we might rise to occasions we can’t even imagine.

Until that day comes, I can think of no better way to pass the time than reading another mystery.

***