What is the personality of this place? What stories and people does it conjure? What do I want readers to feel and think and fear in the time we spend here together? These are some of the questions I ask myself when trying building a fictional place with all the texture of reality and all the dimension and drive of a fully-realized character.

A good crime novel requires many things: a chorus of vibrant characters, high stakes, and a compelling and well-paced plot. It also needs an evocative setting that’s capable of creating unease. For me, whether a book is set in an ordinary suburb, desolate wilderness, or a world-famous city, an author’s attention to setting is what elevates many novels from good to great. An avid reader knows that a fully composed sense of place is more than just stage dressing. Not an inert thing like a theater backdrop against which the action plays, it’s a dynamic presence that provides essential context and grounds the characters’ actions and experiences with authenticity. It makes the story real. And this is as true for police procedurals, as it is with psychological suspense, gothic horror, or any other subgenre.

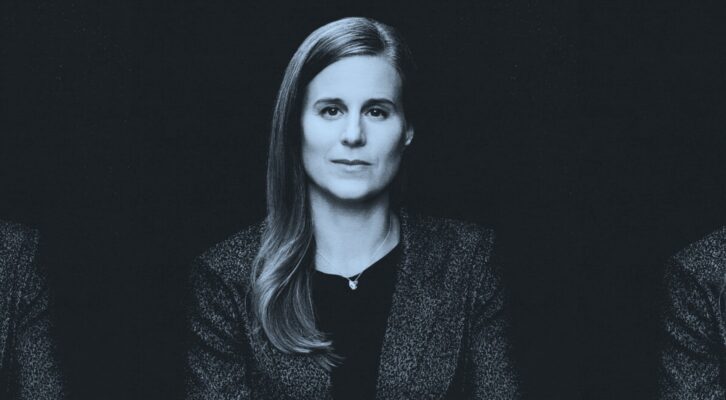

My own most recent novel, The Storm King, straddles several genres, but I know that if I tell you it’s set in a pretty lakeside resort with a vast, abandoned Victorian pier at its northernmost edge, images of this place will immediately spring into your head. These won’t be identical to what I’ve envisioned in my own mind, but that’s okay, the opening chapters of a novel are plenty of time to set the scene so that we can spend the rest of the book exploring it together. But setting is ultimately more than just the physical descriptions of a location.

“Tone” and “atmosphere” are terms often deployed by readers and reviewers when evaluating a novel. These are parts of a literary vocabulary that everyone understands, though if pressed, you may struggle to define them. I think there’s a tendency to parse the elements of a book into discrete categories when the reality is a more of a Venn diagram. Within this diagram, tone and atmosphere share a great deal of territory with setting when it comes to sense of place. Perhaps atmosphere is a bit like the setting’s personality, and tone like a manifestation of the setting’s intentions. Maybe to make a setting come alive we must consider it and develop it as thoroughly as we would any other character.

And that’s exactly what some authors do.

The Dublin of Tana French’s Dublin Murder Squad Novels is a wonderful example of a living, breathing setting that informs the characters and their actions. If you have yet to be initiated to French’s books, you’re in for a treat. Each narrated in the first person from the point of view of a different detective, they’re whip-smart, sinuous, and dark as night. Through the course of the series we witness the waxing and waning of Ireland’s fortunes, the height of the Celtic Tiger economy and the ghost estates of its ruin. Scene-by-scene we gather hints about the burden of new wealth on old infrastructure, and the local texture of neighborhood divisions. We see how roads born of ancient cow paths are now weighted with lanes of gridlocked SUVs, handling the present as poorly as a drafty old house safeguards against harsh weather after a century of neglect. Like a gothic mansion’s cellar, there are places in French’s Ireland you’d do well to avoid after dark.

Not only does French succeed in giving readers a strong sense of the city and its people, but the attention she pays to its geography, diversity, and economic hierarchies are the key to understanding her characters and their motivations. Dublin as a place is crucial to her books. You see this in their class-influenced dialogue and in every calculation of her narrators’ actions. Setting is not limited to the streets that French’s characters walk and the buildings where they live: it’s the language that they speak and the thoughts that they think.

All places have their unique mythologies, and offer rich features and history for an author to draw upon. Of course, this can backfire on a writer if they’re trying to fake their way into sounding like an insider when they’re not (this is a case where the adage “write what you know” comes in handy). Few things break a novel’s spell as effectively as the false note on geography or local lore. But if you’re appropriately knowledgeable about your setting, there’s terrific potential in the alchemy that brings a familiar place to the page. Since this is a transmutation—our reality to your fiction—the choices you make as you craft your novel imbue it with your own stamp. Perhaps in your imagination a famous park is not beautiful, but desolate. Maybe for the purposes of tense scene, a well-known beach town is not welcoming, but sinister. Like a character, every place has its moods, and as the author, the power to develop these is an essential tool in making a setting—even one that exists in the real world—distinctly your own.

Perhaps atmosphere is a bit like the setting’s personality, and tone like a manifestation of the setting’s intentions.I live in New York, a odd place whose countless fictional iterations may well be more familiar to people than its reality, and I get such a kick out of seeing an author get a New York moment 100% right. There are many terrific instances of authors nailing this—Richard Price and Don Winslow’s books are steeped in gritty authenticity—but my favorite recent example is from Victor LaValle’s much-praised The Changeling. The Changeling spends its first act as stirring New York novel, and before it evolves into something darker, there’s a pitch perfect subway scene that’s a brilliant, funny, insightful, and empathetic collision of Only In New York elements.

Imagine the perfect storm of everything you wouldn’t want to happen on a subway happening, and then having the situation, against all odds, work out wonderfully for all involved. There’s a unique pleasure in watching what initially feels like a familiar scene unspool in a wholly unexpected way. As a reader with a real-life acquaintance with the setting, it gave me an invigorating jolt and a sudden insight into the perspective the author wanted me to inhabit. LaValle’s style and generosity is what makes this moment so disarming, but throughout The Changeling, he demonstrates how a well-placed and intimately-crafted scene setting can engage readers and give them a sense of curated reality, of looking behind the curtain to life in another place. This is how I feel when I read Louis Penny’s wonderfully atmospheric Quebec-based mystery series, Robert Galbraith’s evocative, London-set, Cormoran Strike books, and Jo Nesbo’s brooding Oslo-set Harry Hole books. When executed well, readers gain a glimpse into someone else’s everyday world—a world whose secrets and tensions can, for the next three hundred pages, also be their own.

The alternative to taking a real world place and converting it to the page is to create a setting entirely of your own design. No inconvenient geography or traveling logistics to grapple with. No tyranny of facts to maneuver your plot around. No need to rebrand a familiar or, perhaps, over-used location. There’s enormous freedom in inventing your own setting, but taking this route has different challenges. Even if wholly imaginary, a successful setting must have all the depth of a real place, and the characters inhabiting it must seem authentically birthed by these environs. Using a real world location allows you to borrow its mystique, but when you begin with a blank canvas, you must develop these layers of history yourself. Brilliant authors like Ruth Rendell, C.J. Box, and Sue Grafton make this look much easier than it is.

For me, horror has some of the most compelling examples of places that have fully considered mythologies—and perhaps even a wills—of their own. Stephen King in particular excels at this. Take ‘Salem’s Lot, a dazzling portrait of a town slowly succumbing to terror. Though the protagonist has unsettling childhood memories of the ‘Salem’s Lot, when the novel begins, the town is a mostly depicted as a idyllic place to live. It’s the kind of community where people greet each other on the street and don’t think to lock their door. But as events escalate and townspeople begin to go missing, its citizens become afraid to even venture outside at night. The town grows sick, and fear is its cancer. The novel’s pages are drenched with a creeping and then loping sense of dread. This atmosphere is palpable, and the town’s corruption made more poignant by its echoes in its heroes’ loss of innocence and its symbolism as the end of an era for small-town American life. In the good company of many of King’s other characters, ‘Salem’s Lot doesn’t survive his treatment.

There are as many ways to tell a story as there are stories themselves.For me, King reaches the pinnacle of his ability to craft places with the Overlook Hotel in The Shining. The hotel is active presence throughout the novel, and some of the book’s characters are not only influenced by it but infected. An entity as insidious as it is ineffable, it incites many of the plot’s actions through atmosphere and hallucinations. In places, it whispers Iago-like into Jack Torrance’s ear. The characters live in the hotel, but in time, the hotel come to take up residence within them. Not only does King make the Overlook a lushly deep setting and a full-fledged character, the sprawling hotel is indeed The Shining’s true antagonist.

This is not to say that every novel needs a colossal and omnipresent sense of place on the scale of The Shining in order to succeed. There are as many ways to tell a story as there are stories themselves. Writing is about making choices and not every detail you know about your setting will appear in the final manuscript, but the work you do behind the scenes will show in the authenticity of the characters and ground the way they interact with each other and their environment. A close consideration of setting and the decisions about how to present this vision to the reader in a way that they’ll deeply engage with the novel is among the ways a writer best proves their craft.