You have just been murdered in the middle of Fysh street in Chepeside. A blow to the back of the head, in broad daylight! You were just about to pop into the Cheshire Inn for an ale and stew, but it was not to be…these Tudor streets are not as safe as they used to be. Queen Liz has really let things go to the dogs.

But who will avenge your death! Who will make sure the murderer is caught? What will happen to your body? Does anyone give a hoot that your corpse is bloodying the London cobbles?

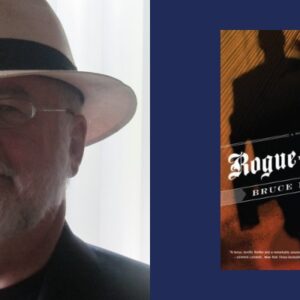

My latest novel To Kill A Queen follows Jack, a thief turned detective in Elizabethan London…but the truth is, if Jack wasn’t entirely fictional, he would’ve been the very first detective England had ever seen. The world of crime and punishment in the 16th century was considerably different to how it is today.

Not that it was lawless….There were plenty of laws. More that the enforcement of those laws happened very, very differently. No Police. No detectives. No forensics. So how did anything get done…how will anyone avenge your untimely death?

Let’s get back to you, poor, dead you, all over the cobbles.

Whether you are a beggar or a well-to-do merchant, a dead body in the middle of the road in Cheapside isn’t going to go unnoticed. It’s a busy road, and there are very nice shops along it! Therefore, the moment you are downed, several people enact the Hue and Cry law.

This is a process by which able-bodied, male bystanders are summoned to apprehend the villain who has been seen committing a crime. Consider it the original Citizens Arrest. Except that, without real police officers to arrest people, this was taken very seriously and was a hugely important part of keeping law and order in the streets of early modern England.

In your case, some busy body called John (lots of Johns in Tudor London) saw what happened. He called out to the killer, summoned his pals, (all of them named John) and they chased the scallywag on foot.

Sadly, the Johns do not catch your killer. They are all terribly drunk and wearing these weird medieval shoes that have no grip. They return with the bad news, just as a horse drawn cart runs over your hand. The significant crowd around your body shake their heads, it’s disrespectful! Landlady Jenny takes it upon herself to walk a few streets down to fetch the constable. Otherwise, you’re going to become a traffic problem.

The constable? A police man? Not quite. A parish constable was not a police officer. Not trained. Not paid. Not full-time. He was a normal man from the parish roped into doing law enforcement duties for one year because it was his turn. Every land owner dreaded being appointed constable. It was like being told, “spend your evenings breaking up alehouse brawls and writing down who stole whose chickens.”

The constable arrives. He talks briefly to one of the Johns. No denying this was a killing. He sighs. You’re causing him a lot of grief. He didn’t want to deal with a murdered body today.

“No one touch the body! They are not to be moved until we can get a coroner here,” he announces.

The constable has to summon a few people now. He needs a Searcher of the Dead, a Coroner and a jury. After he’s done that, he’s on traffic control.

The Searcher arrives first. They are nearly always old, half-blind, and a woman. But in Tudor London they are your first forensic investigators. You’ve bagged Mother Bamford, a living legend. She’s seen to over a thousand dead bodies. The job of the searcher of the dead is to announce the reason for the death; she has no qualifications other than that she’s seen a lot of corpses.

Your reason for death is pretty obvious. But she still takes her time prodding at your gaping head wound. She declares it a murder. Everyone nods their heads, impressed.

The crowd has only grown by the time the coroner finally appears (he had to walk all the way from Bermondsey, across the bridge, for goodness sake). He does the most important thing of all: summons a jury of men from the nearest wards.

They might be any of a butcher, a baker, a man who makes hinges, a grocer who just wants to go back to his shop, or any citizen of good standing he can get his hands on. This group of bewildered civilians is now your crime scene investigation unit.

The jury stand over your body in the middle of the street, (you’ve caused a queue two dozen carriages long! The Constable is having a field day!) and they all swear an oath. Now they must decide exactly what happened. All in public. Outside. Surrounded by gossiping locals.

The coroner questions the Johns (all three of them). He listens to your killer’s description. He takes statements from anyone who will talk.

The jury and Coroner then construct a formal story of your death:

When: A few hours past midday.

Where: Fysh street, Chepeside

How: Blow to the back of the head

With what weapon: Blacksmith’s hammer

And by whose hand: Considering it was a blacksmith’s hammer and the killer has been noted to have brown hair, they’ve decided it’s the local smithy, Robert.

You are finally allowed to be moved. Dead bodies often went straight to the nearest inn, until your kin could come fetch you. You’ve not pleased Land Lady Jenny, thats for certs, but you are picked up by the jurors and left in the Cheshire inn’s main hall. You’ll be buried within the day, if your lady folk are local and loving.

But will your killer ever be caught? The Constable will now take the coroner’s and jurors’ discoveries to the JP. A justice of the peace didn’t investigate crime; he administered it. He didn’t go to crime scenes; he reviewed the paperwork. He didn’t chase murderers; he decided what should happen next.

Unfortunately for you, you’ve got justice of the peace Ben on your case. He’s the JP in my book, and he is…how to put it kindly, a flubberwitted idiot. An attentive JP might summon the witnesses back to his house, he might call the Smithy for questioning, or he might just to commit Robert to gaol on the spot.

Ben, being lazy, and not terribly smart, opts for the latter. You see, he considered the evidence: a blacksmith’s hammer was the murder weapon and Robert and the murderer both have brown hair! Ben felt it was an open and shut case. Guilty. He sends the world weary Constable to arrest him.

And so, you’re murder is solved…perhaps. Or perhaps not. There really was no motive for the smithy to kill you…and the JP Ben was rather slap dash about it all.

In To Kill a Queen, detective Jack is trying to make sure things get properly investigated. After all, someone has just tried to kill the Queen, and that seems like something you shouldn’t leave to beleaguered Constables and incompetent Justices of the Peace.

***