Can you name the five canonical victims of Jack the Ripper? What about the women killed by Ted Bundy? What were Barb from Stranger Things’ hopes and dreams? What did Ashley (the dead girl from Courtney Summers’ I’m the Girl) wish for in her quietest moments?

A true crime aficionado or #JusticeForBarb crusader might have the answers, but most of us don’t. Most of us can name the killer more easily than their victims. Most of us can tell you more about the character hell-bent on avenging a woman or girl’s death than we can about the woman or girl who passed.

Barb is a catalyst for Nancy. Ashley is a foil for Georgia. The victims of serial killers disappear so easily into the background of the stories.

Because the story isn’t about them. Whether they’re catalyst or collateral damage, the girls are not the point. Even in books and movies where we women and girls are the main characters, we’re still so often walking over the corpses of our fellows to get to our triumphant (or not-so-triumphant) endings.

This is the media landscape in which I first learned about the unsolved mystery of the Beast of Gevaudan—an unidentified creature that stalked the French countryside in the early modern period, killing and maiming hundreds.

A certified history nerd, long-time true crime reader, and newly-minted horror author, I, like so many before me, was drawn in by the tale. Was the creature a dog? A pack of wolves? A serial killer in disguise? What was it like to have your region suddenly thrust into fear of a monster in the woods? And how could they have killed the creature but not documented what it was?

I wanted to explore it. I wanted to write about it. But there was a big problem.

A dead girl problem.

The same problem that unsettles me about the stories we have been telling in western media for so long.

I was wary of the dead shepherdesses. I didn’t want to sensationalize them, forget them, use them. I didn’t want the beast to be beastly and worth talking about because of a hundred unnamed girls it stole from history.

So I sat on the story for years, thinking I’d probably never write it. Until an aha moment came for me: What if this was a monster story about saving girls not killing them? What if the beast wasn’t the villain, but the (accidental) savior?

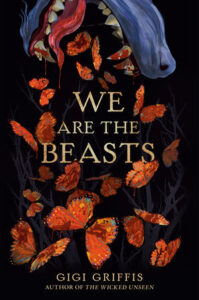

This was the genesis of We Are the Beasts—a story about two teen shepherdesses who see the beast’s terrifying arrival in their region not as a curse but as an opportunity. To stage the deaths of the girls in their village who have been enduring abuse at the hands of the real beasts of our story: bad men.

There is still the (historically accurate) beast stalking a countryside on a killing spree. There are still the unavoidable touches of death upon our horror story. But ultimately it is a tale about the power, humanity, and solidarity of girls against every type of violence. In the end, our girls must face off with the Beast of Gevaudan, but first they address the violence closer to home. And after coming face-to-fangs with the creature itself, they also address the ways that their close-to-home violence created the beastly threat.

It is—in other words—a story about violence against women and girls, but we are not props, not catalysts, not collateral damage.

We are the point. We are the heroes. We are the center of our stories.

I am obviously not the only person pushing back against our culture’s dead girl problem. Especially in the world of YA horror and thriller, things are changing—slowly, surely—for what seems like the better.

In recent years, increasingly more female protagonists who don’t fit the final girl trope have appeared and lived through their stories (like the fabulously furious Laure of I Feed Her to the Beast and the Beast Is Me and Temple of Dead Girls Walking by Sami Ellis). More than ever, girls are allowed to be angry and messy and downright villainous—and still be the character we’re rooting for.

(It’s worth noting that both the characters mentioned above are Black girls—a group historically even more harmed via our cultural dead girl problem—and many of the authors leading the pushback are, as usual, Black or from other marginalized communities.)

Perhaps even more heartening, as we turn toward instead of away from stories about messy, pissed-off girls, their motivations no longer require a body. Maude of Wendy Heard’s Dead End Girls, for example, is driven by a longing for freedom (and more than a little desire to upset her parents). Latavia of Monstrous by Jessica Lewis craves vengeance on the town that tried to kill her. And Bad Witch Burning’s Katrell wants to get rich quick.

Don’t get me wrong: most of these books have body counts. But those body counts aren’t throwaway setup for a character arc.

Even some of the books that do kick off with a female corpse are doing so with more care recently. Like the aforementioned I’m the Girl, whose less-than-explored dead girl feels like more of a commentary on society’s lack of care than of the author’s.

Ultimately, like my journey into the horror genre, my struggle with the dead girl problem is about hope. Hope that we can continue fighting for nuance, humanization, and fewer girls and women used as building blocks for someone else’s story. Give me girls who live. Give me girls who are remembered when they do not. Give me girls fully human, fully messy, fully mad.

So when you stumble upon a story like The Beast of Gevaudan and your writer heart says yes, give me something our culture would never expect:

Girls who survive. Girls who fight. Girls who use the monster to re-write their own stories.

That’s what I’m trying to do with We Are the Beasts. And it’s what I hope we’ll all keep trying to do with the stories that come next.

***