Until recently, being called an “angry woman” was intended as something of an insult. It was like a game of word association. Angry, for women, meant shrill, or strident, or—to quote Donald Trump—nasty. It meant battle-axe, harpy, witch. All things that women really weren’t supposed to be.

In recent years, however, there’s been a turning of the tide.

Increasingly, women are owning their fury—both on and off the page. Increasingly, theorists like Rebecca Traister, Brittney Cooper and Soraya Chemaly—among others—are exploring the ways female anger differs from what we’d conventionally consider a straightforward definition of rage—and in fiction, female characters across the board are expressing their anger, in both subtle and deliciously raucous ways.

And that makes it a glorious time to be reading women in crime.

Because while it’s a joy to see righteous anger, channelled productively into protests, activism, and other work that goes into “the greater good” out in the real world—here’s also a kind of deep, gut-level satisfaction at seeing female rage at its darkest depths, through characters that inhabit the deliciously murky underworld of contemporary crime fiction.

These eight novels all feature female characters who aren’t necessarily good—but they’re sure as hell angry.

And they don’t care if you like them or not.

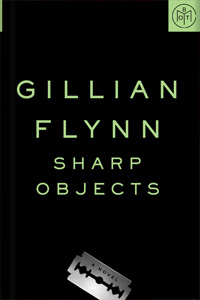

Sharp Objects, by Gillian Flynn

It’s hard not to talk about Gone Girl’s Amy Dunne, when talking about angry women in crime—or, in fact, in modern fiction as a whole. Her “cool girl” monologue, after all, went almost viral in the years after publication, and for good reason—it’s a stunner. And yet, Flynn’s debut novel, Sharp Objects, is, in my opinion, equally brilliant on the subject of female rage.

“Women get consumed,” she writes, ostensibly by sickness and chronic pain – but the women of Sharp Objects are consumed, equally, by the feelings of anger, envy, and bitterness that they force themselves to hide, to suppress: but which reveal themselves in words carved into skin, or acts of unimaginable cruelty. It’s a brilliant page-turner of a book—but with characters so complex, in a world so carefully evoked, that it’s genuinely impossible to put down.

My Sister, the Serial Killer, by Oyinkan Braithwaite

I devoured this short, genius novel in a single morning—and picked up a sunburn in the process, so completely absorbed was I in the world of Korede and her sister Ayoola, the “beauty” of the family, who, as the novel opens, has just murdered her third lover. She claims self-defence, but Korede—her older sister, enlisted to help dispose of the body—is beginning to have doubts.

It’s a brilliant concept—and the execution lives up to the promise. The rising pulse of Korede’s resentment towards her sister—made all the worse as Ayoola sets her sights on the man Korede loves—makes for a gripping, pacy and altogether believable book, with characters that feel completely alive on the page.

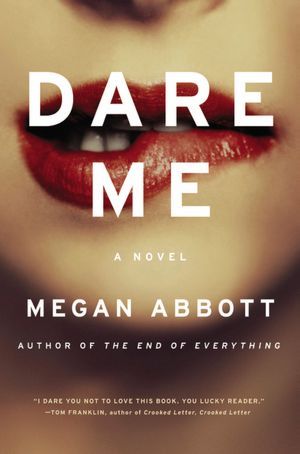

Dare Me, by Megan Abbott

Few novelists can make the fury of the teenage mind come alive quite as well as Megan Abbott—and in Dare Me, the dynamic between the main character, Addy, and her supposed best friend, Beth, practically sizzles with barely suppressed rage. “There’s something dangerous about the boredom of teenage girls,” Abbott writes—and as the novel unfolds, we see this proven true, over and over again.

Abbott is something of a goddess among crime readers and writers alike, and for good reason—her early forays into detective noir are completely unputdownable—and it’s this skill for suspense, and her ability to bring to life the tiny moments of fury that make up the teenage experience, that makes Dare Me the kind of novel I have found myself forcing on everyone I know.

The Girls, by Emma Cline

Emma Cline’s 2016 debut, The Girls, centres around a group of young women surrounding a charismatic leader—a reimagining of life in the Manson cult, in those last awful weeks before the Tate-LaBianca murders, and the aftermath for a cult member left behind.

What makes this book special, to me, is the way Cline picks apart those moments of frustration experienced by the novel’s teenage would-be cult member and narrator. “That was part of being a girl—you were resigned to whatever feedback you’d get. If you got mad, you were crazy, and if you didn’t react, you were a bitch. The only thing you could do was smile from the corner they’d backed you into. Implicate yourself in the joke even if the joke was always on you.”

It’s a steady accumulation of slights, of disappointments and brief, kindling sparks of anger which don’t excuse the actions of the girls in Russell’s cult—but which set the context for the crimes they go on to commit, and which Evie, the main character, finds a disquieting comfort in imagining herself a part of.

Darling, by Rachel Edwards

Darling puts a sharp, unique spin on the fraught stepmother-daughter relationship – infusing an already delicate situation with all-too-relevant racial and political tensions, both in the home and beyond.

It’s testament to Edwards’ skill as a writer that a novel described in the UK as “the first Brexit thriller,” is this much fun to read – but trust me, it is. Both Darling, and her stepdaughter Lola, have their own private angers and frustrations, though they express them in wholly different ways (and with wildly different results.) It’s by turns gripping, incisive, and even, occasionally, bittersweet – a timely, intelligent thriller.

Eileen, by Otessa Moshfegh

Eileen is the kind of book that makes a writer underline whole sentences in black ink—and its eponymous heroine the kind of character that pulls a reader wholly into her dark and seething world. It’s a startling combination of old-fashioned noir, and a comic, bodily grotesque, all set in the mind of a young woman whose disgust knows no bounds.

While Rebecca—the femme fatale figure who appears, midway through the novel, to up-end Eileen’s life—wears the garb and the mannerisms of the traditional woman in noir (and has her own flashes of anger and quiet fury) as Eileen says: “this is my story after all, not hers.” Eileen owns both her story, and her loathing for herself and everyone around her—and it makes for an utterly riveting, wholly unique account of a crime.

The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, by Stieg Larsson

No list of the crime genre’s angry women would be complete without a nod to Lisbeth Salander—a pierced, tattooed hacker (with incredible taste in slogan t-shirts—“I am annoyed” being my simple, but effective favourite) who seeks vengeance, both against individuals who have wronged her, and wider systems as a whole.

It’s impossible not to feel a sense of justice being served as Salander tattoos the words “I am a sadistic pig, a pervert, and a rapist” on to the stomach of a man who has used his position of power to abuse her—especially in a novel first published way back in 2005, when the Weinstein allegations and the sweeping changes that followed #MeToo were a far-off feminist dream.

Larsson’s creation isn’t perfect, either as an individual, or as a straightforward feminist heroine (I’d argue, frankly, that there’s no such thing)—but she is a brilliant, totally memorable, character, and truly one of the angriest women in the genre.

Out, by Natsuo Kirino

Every one of the four women at the core of Natsuo Kirino’s novel, Out—all night-shift employees at a boxed-lunch factory—bristles with rage at the circumstances of their miserable, dead-end lives. So much so that it’s almost—almost—unsurprising when one murders her cheating, gambling husband, and when the others help to dismember and dispose of the corpse.

Out is a remarkable novel, for various reasons—it’s relentlessly bloody, and incredibly bleak, while being quite literally impossible to put down—but one of the things I love most about it is the way female anger is made totally explicit on the page. Kirino isn’t afraid to show her characters feeling their fury, without sugar-coating it—her characters simply are who they are, in all their grotesque, unlikeable glory.

For all the blood and gore, however—and trust me, there is plenty—what makes Kirino’s work really stand out is the moments of pure insight into her characters, and their thoughts. It’s a whirlwind of a novel, punctuated with moments as sharp and incisive as the blades the women use to cut apart the husband’s lifeless, bloodied corpse.