Of all the subgenres of crime fiction, the one I know the least about is the spy novel. I will happily watch almost any Bond movie (especially if it has Daniel Craig in it), but my only familiarity with his novelistic counterparts comes from the one John le Carré novel I picked up in college. If you’d asked me why I avoided reading about espionage, I would have said that while it’s fun to watch beautiful people zooming around exotic locations with outlandish gadgets, I prefer even the most high-concept novels to have a heavy dose of realism. The spy novel is, I would have argued, unrealistic by definition.

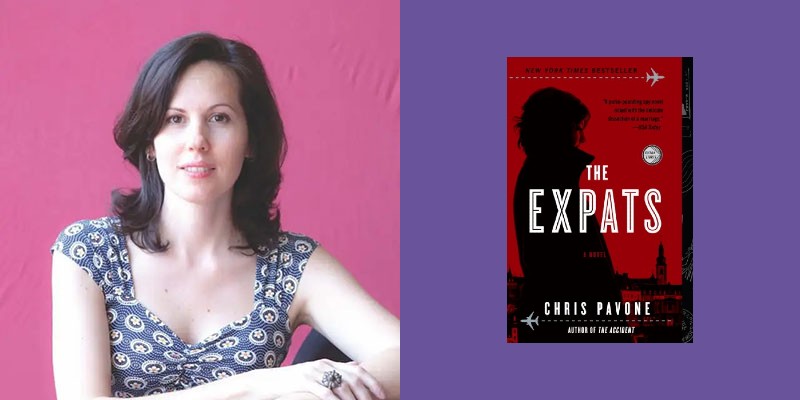

But Chris Pavone changed my mind. In his novel The Expats, the protagonist is a woman named Kate Moore who has moved to Luxembourg with her husband Dexter and two young sons. Unbeknownst to her husband, who believed that she worked for the State Department, Kate has also recently left the C.I.A. In Luxembourg, where Dexter works as a financial security consultant. Kate finds herself at loose ends until she meets Julia and Bill, two fellow expats who might or might not be concealing ulterior motives behind their gregarious exteriors as they attempt to befriend Kate or Dexter. Now Kate must figure out what Julia and Bill are really doing in Luxembourg while keeping her investigations—and her past—secret from her husband.

It’s an incredibly satisfying but also unconventional novel, and Danielle Trussoni knows something about unconventional takes on familiar genres. She’s the author of two memoirs and four published novels: Angelology (2010), Angelopolis (2012), The Ancestor (2020), and The Puzzle Master (2023), as well as its forthcoming sequel The Puzzle Box. She has served as a Pulitzer Prize jurist and for five years wrote the “Dark Matters” review column for the New York Times. Kirkus said of The Puzzle Master that “[Trussoni] is at the top of her game in involving the reader in the puzzle-solving process, making the most of historic settings, including the Pierpont Morgan Library, and making the book’s Da Vinci Code–like trappings pay off.”

What appealed to you most about The Expats?

I really love untraditionally structured thrillers. The writer makes some choices that you just don’t necessarily expect to see in this genre. For instance, there’s all this attention to detail from Kate’s point of view. The book opens with her standing in front of a shop window in Paris, looking at home décor. It’s just really not the place that most thrillers begin. Then, too, the differentiation between her job, which is quite dangerous and violent at some points, and her home life, is laid out in such a beautiful way. I like that Chris Pavone took the time to pause, and to let the consciousness of these characters seep in between the cracks, so the novel doesn’t just depend on plot. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I love plot, but I love books that also have air: great dialogue, descriptions of setting, internal moments with the characters. You see this internal struggle that on the most basic level is between career and kids, which is familiar to a lot of women, even in very different situations. And I love that it’s a man writing this character that I feel very close to. I think he does all of that so well.

That’s such a good point about the beginning. This novel is definitely a page turner, but for me too what was most compelling was Kate’s character. The tension between her job and her family is woven in so seamlessly that you don’t really notice passing from one to the other.

And you believe it, right? There’s never a point where you’re like, I just don’t think that this woman could be both of these people. I really believe it the whole time. And with her husband Dexter too, we know early on that something’s going on with him. Everybody’s lying to each other.

Yes, and yet the relationship feels really authentic. I feel like I’ve seen a million thrillers with a tagline like, How well do you really know the person you’re married to? And it’s usually that they’re a serial killer or they’re pretending to be somebody else or whatever. But in this novel, it’s more the kind of distrust that is part of a lot of marriages, where you’re not necessarily revealing your entire self all the time.

Exactly. It’s a little bit like Mr. and Mrs. Smith in a way, if you want to be really reductive. In another way, though, it’s like a metaphor for a normal marriage.

My husband, who is not a writer, asked me the other day how writers come up with names for characters. Do you have any thoughts about the names in this novel?

Well, Dexter and Kate and Julia are very nondescript names in a way, and I think that’s purposeful. They seem relatable and kind of average-seeming on the exterior, and then when you get inside their heads you find out there’s so much more going on.

Let’s talk about the plot. It seems like the reveals and twists really build on each other as the narrative progresses.

I love how he constructed the plot. It almost feels like a nested box. I don’t want to give too much away, but there’s one scene in flashback where Kate does something kind of unthinkable, or something that’s previously been unthinkable to her. It happens in a hotel room, and it’s like she doesn’t ever quite leave that hotel room, like one part of herself dies there. I saw that scene as the center of the book, and all the other subplots are like larger and larger boxes coming out from that center. I love that structure. We know early on that something bad happened to her, or she did something bad, and you want to know what it was, but you’re also tracking how it has affected her marriage and other elements of her life. The way I read it, the other twists and reveals were secondary to that one central revelation.

I really liked that, because I have to say I’m getting tired of twists that really throw you for a loop. I’ve definitely read a few where I just felt like the twist totally destroyed the book. Like sometimes writers feel so compelled to get a twist in there that the character is sacrificed for the plot device.

There seems to be a perception that the market demands more and more twists, and the more outlandish the better. And a lot of writers might feel that that puts them in a bad position.

And I don’t even know if it’s true. I don’t know if readers do demand twists. I think after Gone Girl, a lot of writers may have thought, “Oh my god, I have to surprise people, I have to completely shock them. There has to be a twist that makes their jaws drop.” But in the books in this genre that I really love, that’s not necessarily true. This is nineteenth century, of course, but with someone like Wilkie Collins, it’s all about character, revelation, pacing. In The Moonstone, they’re looking for an object, and in The Woman in White, they’re looking for a person. It’s all about the hunt for information, and I love that form. I don’t think that there’s anything wrong with a novel that doesn’t have a twist.

I’m teaching a class on Wilkie Collins and Dickens in the fall, and I love that era too. Are you suggesting that maybe the genre would be well-served by a return to suspense through detection rather than through twists?

Well, just speaking for myself, that’s what I like. In my most recent novel, The Puzzle Master, the main character is basically a detective. He’s not a police officer or a private investigator, but he has a brain injury that gave him something called savant syndrome, and it made him very good at solving puzzles. I want to construct a novel with information that the reader needs to find in a way that will be interesting to them. In this novel, it’s done with puzzles—I have puzzles actually in the book—but for Pavone, a lot of it has to do with memory. Sometimes we learn things through flashbacks, and at other times Kate goes to an office and digs through some drawers and it’s more of that Classic Detective Story trope.

This is a novel with a European setting, and a lot of your novels are set internationally as well. Do you have any thoughts on the advantages of an international setting, particularly in this genre?

I love that he’s unrepentantly an international thriller writer. And it’s true, all of my books have an international setting. I find that there’s something quintessentially dramatic about it, maybe because I’m an American who grew up in the Midwest and didn’t start traveling until later in life. For me there’s always something sort of mysterious and promising and hopeful about travel, and there’s also something really alluring about writing about a foreign culture. And I think that it’s exciting when you can’t travel to have a book that takes you someplace far away.

And of course we associate the spy novel with international settings. Do you know much about that genre?

No, I don’t, because I sort of came from a different tradition. I’ve been very interested in literary fiction for most of my writing career, and then I was a columnist who reviewed horror fiction and really dark suspense for the New York Times for five years. I think what’s really exciting for me personally is bringing the tropes and conventions of genre—whether it’s horror, or thrillers, or crime fiction—together with the technique of literary fiction. For me, bringing all of those elements together is what makes a great book.

We have a common love for nineteenth-century fiction, which was published before these genre distinctions meant anything. Sometimes I’d like to go back to that time!

Exactly. No one was saying to Marry Shelley, “Oh, you’re a horror writer.” For the most part, those genre conventions are twentieth-century inventions. But I think the most demanding readers still demand both story and literary quality.