In his foreword to Adam Nayman’s “David Fincher: Mind Games,” director Bong Joon-ho explains his personal dichotomy for classifying films, dividing them into “curvilinear” (like those of Federico Fellini and Emir Kusturica) and “linear” (like those of Stanley Kubrick and David Fincher). Bong makes a point to say that Fincher goes beyond the linear, “[cutting] us with such razor-sharp precision that it almost hurts our eyes and hearts to watch.”

According to Bong’s taxonomy, Fincher’s twelfth feature, The Killer, is certainly more than linear: it’s a series of inch-perfect lines, an A-to-B plot cleanly sectioned into dashes. The lines are drawn taut enough to strangle and are usually punctuated by a bullet, but for the first time in Fincher’s career, he wants you to notice that some of them are starting to fray from the effort.

Our killer is never named, and billed only as “the killer;” you don’t ruin a title as perfectly efficient as this one by second-guessing yourself. Speaking of second-guessing perfection: meet The Killer, a “return to form” for those who didn’t enjoy Mank’s sidestep into Hollywood history and a more literal return to the filmmaking form of Fincher’s mostly death-centric cinema for the rest of us. Back again is the slickly edited violence of Gone Girl and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo; so, too, the eerie killer’s-eye-views of Zodiac and Mindhunter. Throw in a script from Se7en scribe Andrew Kevin Walker and it’s easy to see The Killer as Fincher in dialogue with himself, putting his famous perfectionism in the middle of his own shallow-focused crosshairs and seeing how it squirms.

But first, “the killer.” We’re introduced to Michael Fassbender’s pseudonymous protagonist and his inner monologue via voiceover as he stakes out a kill in Paris, and we never leave his side again. The voiceover is calm but booming, immediately thrusting us into the mind of an assassin and fusing the movie’s perspective with his. That perspective is one shaped less by motivation than by money, and he proudly tells us that he serves “no god, no country, no flag;” if the check cashes, he kills who he’s supposed to kill.

That doesn’t mean he doesn’t have opinions. From the jump, his monotonal musings reveal a skeptical view of the world he sees through his scope, which—paired with his zen-like approach to killing and his quest for life-hacked self-optimization—lends the movie the feel of a nihilistic self-help book written by a murderer. But where some nihilists might take the absence of meaning as an excuse to do nothing, the killer sees that void as an open window through which to aim his rifle. If we’re really just ashes to ashes, the best you can do is carve yourself a nice sand castle out of the dust, and do so by doing your job (any job) as well as you can (no trail).

Or at least, that’s one way of looking at it. And while The Killer wants us to see exactly how the killer sees, it also wants to give us an alternate angle, some cause to second-guess. Fassbender’s droll delivery of the inner monologue recalls Edward Norton’s disillusioned drone in Fight Club and Rosamund Pike’s journal entries in Gone Girl, but while those movies are similarly skeptical of their narrator’s veracity, The Killer turns their sub-text into text by constantly undercutting the monologuer’s authorship.

It does this in subtle ways, at first. The killer has a (hilarious) penchant for listening to The Smiths while he’s murdering, and by simply switching Morrissey’s croons from the non-diagetic soundtrack when we’re looking through the killer’s scope to the diagetic background noise of his headphones when we’re watching him watch his targets, Fincher gives us just enough distance to consider how all those murderous self-help aphorisms sound when you’re not inside their author’s head.

More than that, the movie baits and switches us, clearly establishing the killer as our POV narrator but then showing us the limits of his control. Several times, his voiceover is cut off mid-sentence, forgetting his audience for a moment as he’s distracted by some infringement upon his plan. Elsewhere, the entire filmmaking style shifts to accommodate unexpected developments, breaking from the killer’s measured form to match the chaos around him, as if he’s losing his hold on the film.

Whatever doubts start to pool about our gondola man, we can’t get off the boat, and we can’t stop the trigger from being pulled. But something’s off about this first hit, and some invisible disruption (perhaps our silent observation?) sends his bullet askew, killing a civilian and missing his target. After ten minutes of hearing him coach himself (and us) to “stick to the plan” and “anticipate, don’t improvise,” we realize we’re meeting this killer-as-perfectionist on the worst day of his life: the day things don’t go according to plan.

The misery continues: after some forced improvisation during his escape (“WWJWBD,” he winkingly wonders while fleeing the police: ”What would John Wilkes Booth do?”), he returns home to the Dominican Republic only to find his seaside villa broken into and his girlfriend brutalized as a swift penalty for his failure to execute. That’s about enough uncontrolledness for this killer’s lifetime, and he spends the remainder of The Killer’s brisk two hours trying to shorten the lifetimes of those responsible, working through his hitlist in an attempt to clean up the mess he’s made.

This framework suits a film about an assassin, giving us similarly structured chapters for each hit (even killing can become banal) that nonetheless retain a distinct flavor influenced by their various locales—each of which inspires the killer to modulate his approach. After introducing the tension between control and the unanticipated lack of it, the rest of the film acts as a dialectical examination of that conflict, forcing the killer outside of his comfort zone even as he tries to convince himself (and us) he’s still driving the car.

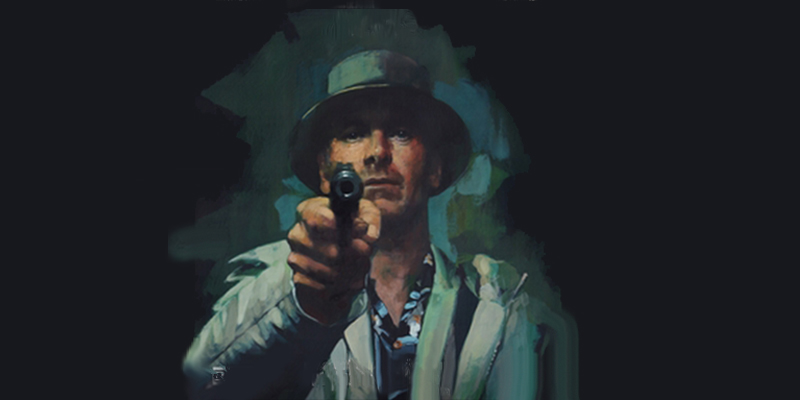

To his credit, he is very convincing. Always operating with optimum efficiency and caution, he treats his body like a temple (McDonald’s aside; to his point, it is ten grams of protein for a euro) and leaves no footprints, digital or otherwise. Pre-kill, he does yoga until his heartrate goes sub-60bpm; post-kill, he breaks down his gun and discards its pieces in storm drains and garbage trucks from the back of his speeding bike. He rarely stops moving or keeps the same phone between hits, and he always hides behind his chosen camouflage: a bucket-hatted outfit inspired by the type of German tourists he claims everyone ignores.

The movie itself is just as sleek and economical as he is, relegating his backstory to the mere existence of a girlfriend to avenge and one throwaway line about an old professor who “suggested I stop studying the law and start skirting it.” It’s a character study in minimalism, the man as a summation of his actions. And why not? The actions can’t lie, and besides—painted as they are in crisp blues and yellows by cinematographer Eric Messerschmidt, they look really, really good even when they’re really, really ugly. From hit to hit, the patient stillness of the hunt is interjected with bursts of violence, as shocking in their graphic execution as they are matter-of-fact in their framing. As the killer’s sure to remind us, this is just a job, albeit one he’s concerningly good at.

Rather than positioning each hit as a long-term mission to be solved, The Killer tees the targets up as a series of brain-teasers for a lethal puzzler, like a case-of-the-week serial condensed into a feature. Without breaking pace, the movie and its man glide through these chapters like a barracuda, eliminating obstacle after mini-obstacle with ruthless determination. This steady cadence of problem-solution would be satisfying if it weren’t so chilling; under Fincher’s seductively entertaining direction, it might be satisfying regardless.

*

“I’m not a genius,” the voiceover tells us, but it doesn’t take one to recognize the similarities between the killer and his director: he of the endless takes and the laser-precise eye and the perfectionist approach to moviemaking. You could drop Fincher’s line about there only being two ways to shoot a scene and the other way being wrong into the killer’s voiceover and no one would blink an eye, and when the killer tells us you have to be patient to do this job, he might as well be Fincher coaxing an actor back to set for take #100. These are two men similarly obsessed with perfection and planning, exacting excellence at gunpoint if necessary—which makes it all the more interesting when the movie goes on to puncture their airtight plans.

By the time the first hit goes awry, the movie’s form has so merged with its killer that the film itself seems startled by the deviations to plan, abandoning its too-neat frames and water-smooth pans for dazzling, run-and-gun handheld shots—something relatively unheard of in the Fincher canon, but all the more fascinating as exceptions to prove the rule. These improvisations take on different shapes, including a desperate sprint through the jungle and a show-stopping brawl with a roid-raging Floridian, but they all work in fascinating conversation with the movie’s surrounding neatness, an organized director coloring outside of the lines.

Even when the plan isn’t being disrupted at form-altering levels, there are other cracks in the killer’s well-manicured psyche. Despite his claims of amorality, his monologues suggest the shifting ink-blots of a modern Rorschach. Like the Watchmen vigilante, he roams the streets unseen, railing against both the “few” and the “many” of society even as he self-consciously avoids confronting his role in it.

Perhaps that’s because he’s part of an even more-select “few” than those he looks down (or up) on. His individualistic tirades are proven correct at times (he’ll tell us not to trust anyone, then we’ll see that the innocent-seeming person he just killed was holding a knife), but that’s because he’s not mixing with the “many.” With the exception of an early target who gets a raw deal, the population in his crosshairs are exclusively people involved in his hyper-niche bubble, an insular world of assassins that he confuses for the world at large.

And lest he judge too quick, his apparent disdain for certain aspects of modernity (not McDonald’s) bumps up against his own reliance on Amazon and WeWork to execute his hits, to say nothing of how easily he fits in with the “normies” while shadowing a target in an Equinox stand-in. Unlike Rorschach, he doesn’t deem his targets worthy of killing for their perceived moral or cultural lapses; he just exploits those lapses to kill them more easily.

It’s something like a Wall Street shark trying to write a book about how to work with people and only writing a book about how to work with sharks. We write what we know, and if The Killer is a murderous self-help book, its perspective is blinkered. But maybe that’s the point: for all of the film’s thrilling digressions into improvisation, the killer always regains the upper hand. And for however well he maps onto his protagonist, Fincher is still one degree removed; loose as they feel in the moment, the killer’s improvisations were no doubt rigorously choreographed by Fincher as purposeful counterpoints to all the control around them.

How interesting, then, that this movie about the limits of control seems, by merit of its near-perfect construction, to have been produced under its director’s typical perfectionism. Similarly accused control freaks Wes Anderson and Christopher Nolan also made recent films that intentionally exposed the boundaries of their imposed artistic orders, but Asteroid City and Oppenheimer make concessions to chaos in an attempt to find some wild new truth, to brush up against infinity. Fincher, meanwhile, seems to have unleashed chaos only to reestablish his dominating control over it.

Or has he? In the end, The Killer and the killer make unexpected choices that cast doubt on their true allegiances, or whether they have any at all. Are we to conclude that the killer made it to the finish line by learning to loosen his grip, improvise, and even empathize—joining in with the happy, normie “many”? Or did he simply kill who he needed to kill in order to clean up his mess, violently returning his life to the perfect order only he can see from the mountaintop of the “few”?

If The Killer is Fincher’s metaphor for the havoc the filmmaking process inevitably wreaks on a perfectionist filmmaker (or maybe, the hellish experience of processing an imperfect world through a perfectly ordered mind), then what does it mean that he’s still standing, twelve near-perfect movies later? Does that make him a secret member of the go-with-the-flow “many,” or one of the conquering “few” stuck explaining the difference to the rest of us? Either way, what a blast it is to watch him work out the answer, as cool and calculating as ever but with a new vitality born out of (controlled) chaos.