“Raymond Chandler once wrote that a dead man was the best fall guy in the world because he never talked back. I begged to differ.”

—Cleo Coyle, The Ghost and the Haunted Portrait

Years ago, I read The Ghost of Captain Gregg and Mrs. Muir by R.A. Dick, the pen name for author Josephine Leslie. The book was a bestseller in 1945. Two years later, Hollywood adapted the story into a now-classic film, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, featuring Gene Tierney, Rex Harrison, and one of Bernard Herrmann’s finest scores. Two decades later, a new generation discovered the story via a 50-episode television show.

The book was wise, the film moving, the TV series entertaining. What influenced me most, however, was a realization about the era in which the writer penned her novel. World War II was coming to an end, and many women were grieving the loss of their husbands. Ms. Leslie gave these women the story of a young widow who is haunted by the spirit of a dynamic sea captain, one who “dictates” a bestselling book to her.

I appreciated the comfort that tale must have brought to war widows of the time. The Ghost and Mrs. Muir made vivid the idea that spirits are looking after us. Whether the spirits are real or residing within ourselves—as imagination, passion, or creative potential—the notion is an uplifting one.

From a more modern perspective, the story could be viewed as challenging ideas of binary gender identity. Inside a repressed widow (one who secretly never loved her husband), a male voice and perspective haunts her. This masculine spirit leads Lucy Muir toward a more authentic life in which she is able to express how she truly feels. She makes choices that release her from a conventional prison, breaking the constraints of what others “think” she should do, who she should be, and how she should live.

Like all well-drawn characters, Lucy Muir has faults. She backslides, fights her internal spirit, and does things she comes to regret. The core of the fiction, however, is a tale of feminist empowerment. Though I wouldn’t be born until decades after Ms. Leslie penned her novel, her story inspired me as a woman—one who’s made many unconventional life choices—and as a writer.

It was Ms. Leslie’s concept of a widow secretly possessed by a masculine spirit that fueled my vision for The Haunted Bookshop Mysteries, which I write in collaboration with my husband (making “Cleo Coyle” a de facto gender-blended entity in itself). Here’s the wrinkle though, The Ghost and Mrs. Muir is not a mystery.

Back in 2003, though Marc and I started with an homage to Ms. Leslie’s concept, we worked hard to create a whole new world of original characters, settings, and stories within a functioning structure that could support multiple works of crime fiction. For those of you not familiar with our cozy/noir hybrid of a series, here’s how that development went…

Like our chosen protagonist—a young, widowed bookseller named Penelope Thornton-McClure—Marc and I grew up loving books, so the idea of running a bookshop was already a happy fantasy to explore.

Because of our mutual admiration of Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, and the plethora of pulp writers from the Black Mask school, we gave Penelope the backstory of having a father who was a small-town cop and a great fan of these writers. This is how she developed an affection for the adventures of Philip Marlowe, Sam Spade, and the other trenchcoated antiheroes of the dark city streets.

One day in her bookshop, under the stress of dealing with a difficult author, Pen hears a gruff, infuriated voice in her head. Being a polite “do right” Jane sort of person, she can’t imagine where this outspoken voice came from. She would never use such blunt and colorful language.

Or would she?

Was this assertive, masculine voice really haunting Pen? Or was her alter ego expressing itself through an iconic character like the ones she discovered in her father’s library?

The “ghost” in question is Jack Shepard, a private investigator who was famously gunned down in 1949 in the very building where Pen now runs her bookshop.

Whether the ghost is an actual apparition or the vivid imaginings of a stressed and lonely widow in search of a confident and powerful voice, Jack becomes Pen’s invisible companion. When big-city crimes occur in her small Rhode Island town, Pen seeks the counsel of the wisecracking New York gumshoe in bringing the cunning culprits to justice.

As longtime fans of film noir as well as the Black Mask writers, my husband and I also took pleasure in developing memory flashback subplots for our ghost character, Jack Shepard—along with a fictional device that allowed our prim bookseller to join him in the 1940s for a kind of unconventional PI school.

This offbeat, gender blending entity of a prim, repressed bookseller possessed by a hardboiled ghost appeared to delight readers as much as the inspiration for our series originally intrigued me. Pairing Jack’s hardboiled darkness with the lighter character of Penelope proved a winning combination for enough readers to make our books national bestsellers.

After our first Haunted Bookshop Mystery, The Ghost and Mrs. McClure, was published by Berkley in 2004, Marc and I wrote four more in the series. Then, we stopped writing them. There were many reasons why—one being the demands of our Coffeehouse Mysteries, a long-running series that is still going strong with 19 titles, and the 20th coming next year.

Another reason was the climate. In 2009, the rise of e-books and self-publishing rocked the book trade. Predictions about the “death of print,” the demise of booksellers, and the end of traditional publishing were all the rage. So, we decided, until the atmosphere surrounding the book business (a trade, don’t forget, that we were writing about via Pen’s profession) became a little saner, we would focus on a single series and put our Haunted Bookshop Mysteries on hiatus.

What we never expected was the outcry that followed. Emails, messages, and public comments from fans urged us to revive the series. We expected this to die down over time, but it didn’t, and the five-book backlist never went out of print.

Our readers’ steadfast devotion was the primary reason we made our ghost reappear. To our publisher’s credit, they supported our decision to bring Jack and Pen back, and our first new Haunted Bookshop Mystery was released after nearly a decade. The Ghost and the Bogus Bestseller became an actual bestseller and a Suspense Magazine best of year pick. It was the kind of comeback story we’d hoped for. And (so far, at least) we haven’t been ghosted. Not that the world hasn’t tried.

These recent pandemic years were no picnic. Marc and I live and work in the same Queens rowhouse we’ve occupied since before we were married in 2000, which turned out to be less than a mile from ground zero of New York City’s worst Covid outbreak. Fleeing our home was never an option for us. We chose to remain in our community, taking care of our rescued cats, managing scarcities, and the anxieties that (no doubt) all of you were feeling, too.

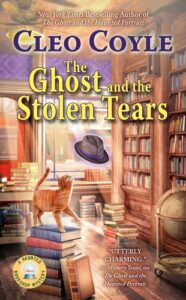

During that time, the absorbing practice of writing became an effective coping mechanism. The Ghost and the Haunted Portrait, The Ghost and the Stolen Tears, and The Ghost Goes to the Dogs were three of the four books we wrote during that time, and there was never a better time to have Jack’s hardboiled voice in our heads, a character who’d spent years surviving the despair of the Great Depression, the bloody battlefields of the Second World War, and the grit and graft of 1940s New York.

Jack’s brand of hardboiled goes beyond mere cynicism. Modern life provides enough of that—the kind of bleak pessimism that undercuts survival. Sure, life is filled with crushing disappointments, disillusioning betrayals, and devastating loss. But it’s also packed with ridiculous absurdities. Stupid funny screwball stuff. And, hell, just because we’ve taken body blows, doesn’t mean we have to lie down and die. In Jack’s world, hardness comes from self-reliant spareness, paring things down to their essentials, finding the lightness in the dark, then getting up and getting on with it. We couldn’t have been better served by our spirit’s approach to troubling times.

In the end, like our readers, we hope Jack—and all of the characters we’ve written over the past twenty years—will never stop haunting us. We consider them to be good friends, and nobody wants to lose a friend, not even a fictional one.

***