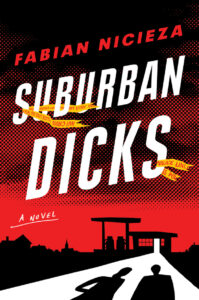

What’s it like to see your debut novel, Suburban Dicks, come out the same year you turn sixty? Pretty cool. What’s it like to wonder why you waited thirty-five years to write it? Pretty vexing, I’ll admit.

But the source of that vexation is complicated. I am a comic book writer. I have written lots of other things, but I am best-known (where I am known at all) and have had my greatest success on that platform. I made my bones in the late `80s through the mid-90s, during a time of tremendous quantitative success and questionable qualitative output. I was party to quite a bit of both of those categories.

I came of age in an industry that had just begun to fight back against the nauseatingly repeated “BAM! POW! SOK! Comics Aren’t Just For Kids Anymore” media coverage. The `80s were a time when mainstream superhero comics were “growing up.” The industry produced Watchmen and Dark Knight Returns, Swamp Thing and American Flagg, Sandman and Maus.

I was a part of the generation that wanted to prove we were not the disparaging stereotype that mainstream publishing and adult audiences thought us to be. But, admittedly, underlying that righteous fervor was a foundation of creative insecurity.

Are you a REAL writer? Even the greatest comic book writer of all time would be practically useless without the artist telling the story in a visually engaging manner. I am of a time when the artist was more “important” than the writer, and to this day I believe that to be true, though the industry’s pendulum has swung too far in the other direction. Graphic storytelling is a visual medium. Your job is to tell your story to an artist in a way that they can then interpret visually for an audience.

I acknowledge that, for the most part, comic book writing is the antithesis of prose writing. So, how did all this experience writing in one medium hurt or help writing in another?

I think being a professional comic book writer helped me immeasurably in the writing of the book, though that’s a reflection I make in hindsight. While writing Suburban Dicks, I wasn’t giving it much thought. I was just thrilled that I felt far more comfortable in prose than I ever had been before. I came to find my own voice instead of poorly copying the voices of other authors. (There is nothing sadder than being a poor-man’s James Ellroy, and I know because, twenty years ago, I tried to be.)

But… I also didn’t want the work to be thought of as a superhero, science fiction, or fantasy genre book. I was writing something others didn’t know me for, but because the story (and its sequels) had been festering in my brain for decades, I thought of myself in a way others didn’t.

Bam! Pow! Sok! Screw it, I was going to write a sarcastic suburban mystery!

Before I started, I only gave myself one hard rule: No tights. No fights. No flights. I didn’t want the book to have any of the tropes or conventions that was an expectation and/or requirement of the genre work I’d done in the past. And I stuck to that rule. Anything else, language, equal-opportunity sarcasm aimed at the cultural diversity of the book’s setting, and the overtly anti-isolationist tone of the narrative were all fair game for me, and frankly, had been part and parcel of my work throughout my career.

The nuts-and-bolts introspection about how my experience helped my work has only come after the fact. Now, while I’m being interviewed for the book or talking with fellow professionals about the process, I’ve I come to understand (and appreciate) what thirty-plus years brought to this process.

Writing comics made me very confident and facile with dialogue

Comics require you to hone a character’s voice. Cadence, intonation, intent—all are managed into balloons of a few lines or less. Space restrictions also force you to be economical with your word count.

The “smell test” is if you close your eyes and someone reads the dialogue out loud. Can you tell which character is saying what line?

Writing comics have given me a strong sense of structure and pace

Comic stories have a set page count, that limits the number of scenes you can have in an issue, dialogue in a panel, etc. Because mainstream comics are a sequential publishing product, more akin to soap operas than feature films, your story has to entertain on a self-contained basis, while also planning for it as part of a longer whole.

I have broken down an 8-page story about a down-and-out boxer’s death and a 22-part 500-page multi-title storyline with operatic intergalactic complications. You learn a tremendous amount about structuring and pacing when working to a variety of length expectations.

Writing comics provided an unabashed flair for the “dramatic”

An end to a chapter for me was no different than a cliffhanger in a comic—it’s all meant to excite a reader to want more. Don’t the best books make you read “just one more chapter” before going to sleep? In my mind, that is a very close cousin to a “To Be Continued!” blurb at the end of a comic.

All of that led me—consciously in this case—to shoot for a strong beat, line, or hook to end my chapters on.

Writing comics taught me to embrace conflict, both external and internal

Superhero comics are about conflict. Man vs. Man, Man vs. nature, and—when done right—Man vs. Self. Now that conflict tends towards the hyperbolic “disaster porn” that’s now been embraced by feature films, but at its best, the conflict boils down to: our hero fighting against all odds to do the right thing against someone who is doing the wrong thing (and hopefully because they think it’s for the right reasons).

I wanted my characters to be right and righteous, but also to face consequences for their actions. I wanted Andie Stern and Kenny Lee in Suburban Dicks to be flawed and noble, the way Marvel Comics taught me heroes were supposed to be.

Writing comics kept me on a self-imposed deadline for every stage of the work

Mainstream comics are a monthly grind and luxuriating in the time that prose affords a writer was, for me, a surefire excuse for never finishing the work (much less when it wasn’t being written to a contracted deadline).

I come from a world where if an editor asks for delivery on Friday, my job is to get it to them on Thursday. Overnight scripting of entire issues, quick emergency rewrites or art corrections, etc.

I never had the time to let the work breathe, but I admit, I am starting to learn to appreciate it. My general aggressiveness was well-suited to the pace of comics publishing, and I certainly hope I am given the time in book publishing to luxuriate in the time allotted to complete the work.

I don’t think Suburban Dicks would have gotten to the point that it has if it weren’t for the experience I had gained over three decades filled with incredible highs and lows. The confidence of career success merged nicely with the insecurity of “Are you a REAL writer?”

The book is a sum of all its parts—all of my parts—and I would never have written it, much less to any level of success, without the foundation it was built on. TO BE CONTINUED…

***