Arthur Barry was a precocious and versatile lawbreaker. As Dean Jobb tells it in his brisk, beautifully written new book, Barry was a beer-drinker at seven and a safecracker’s errand boy at 13. He made his first theft at 15, breaking into a house and stealing some cash. In time, Jobb writes in A Gentleman and a Thief: The Daring Jewel Heists of a Jazz Age Rogue, his subject matured into “a bold impostor, a charming con artist, and a master cat burglar.”

Barry, in the 1920s, was a 20-something war veteran when he began breaking into rich New Yorker’s homes. When police finally caught up to him, the arrest was on front pages nationwide. Why? Because he stole from oil tycoons, financiers and prominent heirs, pocketing jewels that would today be worth tens of millions of dollars. And because he was the antithesis of the crude oafs frequently featured in the era’s popular true-crime magazines.

As he crept through mansions after midnight, Barry sometimes encountered homeowners. When this happened, he was suave and solicitous—a gentleman thief who might fetch a glass of water, some aspirin and a bathrobe for a burglary victim. Said one such woman, “I know he’s terrible, but isn’t he charming?”

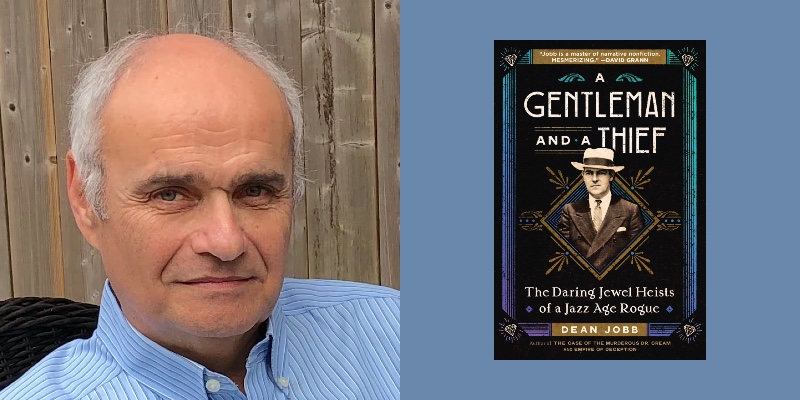

Jobb, the author of, among other titles, the award-winning The Case of the Murderous Dr. Cream: The Hunt for a Victorian Era Serial Killer, discussed his latest book in a recent video interview.

Tell me about how Barry got his start. What was he doing when other kids his age were delivering newspapers?

He always said he was big for his age. After he started hanging out with an older crowd of guys who did things to make five bucks here and there, he became a courier for a fellow who was making explosives for safecrackers. Barry would take, by train, suitcases stuffed with cotton and a bottle of homemade nitroglycerin. In a great story Barry related, he said the fellow told him, Don’t shake it. And don’t move it too much. And try not to drop it. He was in and out of trouble with the law, and he ends up in a reformatory. But then he goes overseas and becomes a first-aid man—a medic, in today’s terms—during World War I, and he’s wounded and gassed.

He’s nothing less than a hero, as you describe it in the book.

He made heroic efforts to save men on the battlefield. I thought it was important for readers to know that. He didn’t start out saying, I’m going to become this master jewel thief. He was unlucky in that his unit was one of the ones held back for a year to occupy Germany after the Armistice. So by the time he gets home it’s late 1919 and all the jobs are gone. He thinks, What am I going to do? I’m stuck here in New York, the economy’s bad. And he almost literally started going down a checklist: I don’t want to be a bank robber; I don’t want to hurt people.

Right, you make clear that violence wasn’t his thing.

At times, he does carry a gun. He claimed it was so they wouldn’t take him alive. But he was a sneak thief—he would go in when nobody was home or when they were downstairs at dinner.

He becomes known as a second-story man. What’s that?

The term came from a play by Upton Sinclair. This was someone who would use a ladder to climb into a second-story window when nobody was home, or nobody was upstairs, and rifle the house.

And he wasn’t bothered if people were in the house?

One thing I tracked was almost a development or a refinement of his methods, and of how he identified these targets. Sometimes he’d crash parties in a tuxedo, blend in and use that as a chance to look through the upstairs and see if there’s an alarm system, maybe unlock a few windows first before going back in later. He found that it was dicey to break into a house when people were there. He was shot at a few times. But he also found that he didn’t want to break in when people weren’t there, because if they were out they had their jewels on. If they were home and he woke them, he had to deal with them. He would put them at ease—even if he had a gun in his hand—and say, Look, sorry I’m just here to steal the jewels. I’m not going to hurt you. He was so good at this, so soothing, that he got called the Gentleman Burglar.

He called the people he stole from his “clients”? How did he decide which houses to target?

The mastery, the smarts he showed in this—I do think readers will not be able to help themselves from rooting for him sometimes, because he is robbing people who have more money than they need. Jewels are not a useful item to own. You can own a fine mansion and still live in it. What do you do with jewels? You show off how rich you are. To find them, he hangs out at a restaurant in Central Park where women would socialize and wear fine jewelry. He’d see what limo they were picked up in, pretend to be a cop, call the police station, say there’s been an accident and ask them to run the plates to find out where they lived. He also read the social pages of the New York papers. He called them his accomplice, because they said who was in town, who was in Palm Beach, and showed women in their fine jewelry. These would become future targets.

You do a nice job of showing how jewels were very much on the American public’s mind in the 1920s. King Tut’s riches were revealed, and World War I shifted a lot of jewel transactions from Europe to New Yorck City.

I quote some of the news of the time: Diamonds are hot! People who did well from the war—it’s hard to believe, but some people didn’t seem to mind being known as war profiteers—thought this was a great way to flaunt their wealth. One of the police officials in New York, who of course had to try to solve every jewel robbery there, said, It would help if some of these rich women weren’t running around looking like a pawn shop window.

Crime coverage boomed in the 1920s. The Daily News covered crime in the most sensational way possible, and there were several large-circulation true-crime magazines. So is it accurate that Barry’s crimes were famous long before anyone knew his name?

That’s right. And even the more established broadsheets like the New York Times would put his crimes on the front page. But yes, this was exactly what the Daily News looked for—crime and prominent people.

His heyday is the mid-1920s?

He started going up to Westchester County, New York in 1920, and it’s 1923-24 when he starts targeting the ultra-rich—the Rockefellers, a Woolworth five-and-dime store heiress.

What does the public think? Are they pulling for somebody who takes the gems that a Woolworth heiress wears around town?

The New Yorker archives have a lot of articles about that particular heist, which was from a room at the Plaza Hotel. The New Yorker just had a field day, because Jessie (Woolworth) Donahue would show up at social events elaborately bejeweled, with her $700,000 pearl necklace. And so there was some derision: Well, she can replace that at her father’s five and dime store.

These were serious crimes. He violated people’s privacy. He shattered their sense of security. But he didn’t hurt anyone. And he did perfect this soothing approach, which really makes him a different kind of criminal. It certainly made him a more enjoyable character to bring to the page. He didn’t have a cruel streak or anything. And he even openly said, If a woman could afford this kind of jewelry, she’s not going to go hungry if I rob her, right?

When he sells these jewels to gem dealers in New York City, he’s getting less than full value, because it’s an open secret that they’re stolen.

He said 10 percent, maybe 15 percent of their value. He doesn’t have a lot of choice, but he griped about it. But then again, it was just a few minutes’ work—after a lot of planning. He would meticulously stake out mansions, check for security guards. If there were dogs, well, he always had a pet dog, so they’d smell a scent on him and that put them at ease. Or he’d bring some steaks and that would look after the dogs long enough.

And what does he do with the money? He’s a “plunger,” as you describe him—what’s that?

It’s someone who, like it sounds, plunged right into the Broadway nightlife. He was like Nathan Detroit, the Guys and Dolls character. He loved gambling. He said he preferred gambling to sex. He would win spectacularly, and he would lose huge pots. When the money ran out, he’d just go steal more jewels. He made no bones about it.

It was a generation F. Scott Fitzgerald captured—live for the moment. And Barry found a way to finance the lifestyle he wanted. He regretted it later. He didn’t save anything, there was no buried treasure. But he said, That was the times, you lived for the day. It was wonderful to have this character who personified the jazz era.