I am a bad boy. I have spread mustard on a sandwich as much as ten days after its use-by date. I have loitered where signs are posted that forbid loitering, not because I wanted to loiter; I was in a hurry to be elsewhere, but I wasn’t going to let anyone tell me where I couldn’t loiter. I have washed garments that I was commanded to “dry clean only.” Really, when it comes to obeying the rules, I am a dangerous nonconformist. This has also been true in my writing life, and while I’m not proud of it, I’m not ashamed, either.

When I began to write cross-genre novels with Strangers in the early 1980s, my publishers knew I was doing something unconventional, and they knew they didn’t like it, but at first, they couldn’t put a name to it or explain why such work made them uneasy.

Initially, I didn’t realize it was the manuscript of Strangers they found off-putting. I thought it must be something about me that repelled them. Something about my face? Everything about my face? Or could it be that I shouldn’t have eaten an anchovy and horseradish sandwich on garlic bread for breakfast that morning?

No. It was Strangers that made their eyes water and induced in them a shortness of breath equal to that of end-stage bacterial pneumonia. The novel was a thriller with a science-fiction premise, a love story, and a paranoid conspiracy tale, written as a mainstream novel, with a theme of transcendence. I was pressured to cut the 940-page manuscript to 450 pages and turn it into a flat-out sci-fi horror novel with a smaller cast and a theme of existential dread. I had considerable respect for the publisher, but I knew why I had done what I’d done, and I knew it wouldn’t work if half the text was cut.

My next book was Watchers: a dog story, a chase thriller, a mafia tale, a love story, and a monster story, with a sci-fi element, written as a mainstream novel. No one at the publishing house knew what to call it, but they all loved it because of the adorable golden retriever. They put bloody monster footprints on the cover and called it “horror,” much to my dismay. It hasn’t been labeled “horror” in 30 years and nevertheless has sold over 12 million copies worldwide. It has also been made into four movies so bad that it’s a wonder a pack of otherwise loving golden retrievers hasn’t attacked the producers, directors, and screenwriters with all the savagery of rabid wolves.

Watchers was followed by Lightning, which was a time-travel story, a thriller, a love story, somewhat of a comic novel, which tackled the theme of fate. I’d written it because by then I enjoyed watching my publisher’s head swell like an over-pressurized boiler, with steam issuing from her ears. The big complaint this time, however, wasn’t the mix of genres. The lead character was born on page one and was a child throughout the first third of the novel, which made this (I was told) a young adult novel. I was counseled to put Lightning on a shelf and not publish it for seven years. Otherwise, it was certain to destroy my career. I was told that kids would not read books their grandmothers read, and grandmothers would not be quick to read what their grandchildren enjoyed. I said to the person who was my agent at that time, “Was Oliver Twist a young adult novel? Did it destroy Dickens’ career? Was To Kill a Mockingbird a young adult novel? Ray Bradbury’s Something Wicked this Way Comes?” My agent said, “Honey, who’s to say they wouldn’t have been even much bigger successes if they hadn’t published books with children as main characters? Just be grateful the publisher is going forward with Lightning—and don’t write any more with kids as the main characters for a third of the story.”

By the time I delivered Midnight, my publisher had come up with a term to describe what I was writing——cross-genre novels. They were happy to have a label for the sales department to use, though they didn’t like what it implied and preferred that it not be used often. Now, almost forty years later, cross-genre novels are published every day. I doubt that I founded the form, as has been said, but I will take responsibility for being a Typhoid Mary who infected others with the desire to write them.

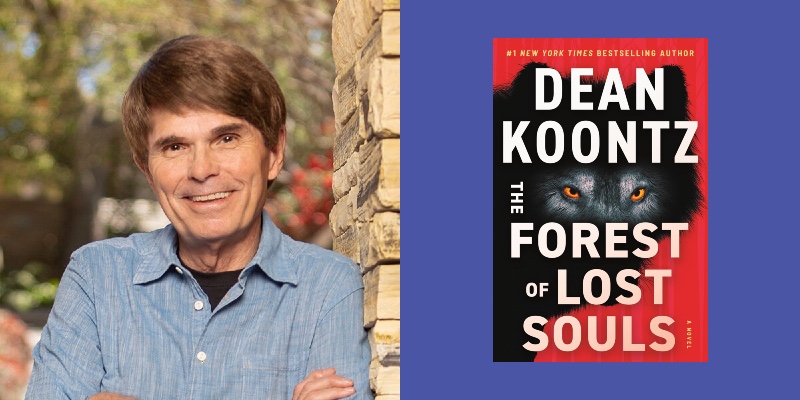

I often produce cross-genre fiction because as a reader I enjoy all genres, including literary fiction, which I consider just another genre. Because I don’t write outlines and I begin with only an interesting premise and a main character, I never know what genres will flow naturally into the novel as it grows. In The Forest of Lost Souls, I was surprised to find myself inspired to begin with a short chapter about an albino mountain lion native to the territory where the story is set. When that chapter was finished, I realized the book was about the enduring nature of myth, the truths that myth conveys about human nature, and the power of myth to lead us unconsciously to commit ourselves to right action. Thus, I knew early that a light note of fantasy must be one element of this cross-genre novel.

Now, bad boy that I am, I must be off. There are countless mattresses bearing tags that say it’s a federal crime to tear them off. To preserve our democracy, I must think of myself as Beowulf and rip those tags as if they are the monster Grendel. See you in Valhalla.

***