If you’ve a bad, bad past

It finds you out at last.

—From “A Bad, Bad Past” (Lyrics by Clifford Orr)

Introduction

The practice of “drag” or cross-dressing—i.e., performatively adopting the dress and manners of the opposite sex—is familiar in detective fiction published between the First and Second World Wars, where, with devious and often deadly courses in mind, men may mum as women and women as men. Likewise, at all-male Ivy League universities in the first quarter of the twentieth century, young men decked out in drag commonly performed female roles in college theatricals—albeit strictly for comedic, rather than criminal, purposes. While drag acts, as it were, continued to take place in crime fiction throughout the twentieth century, college drag declined drastically in the 1930s after the American public, stoked into a panic by enforcers of traditional gender roles, began associating cross-dressing on stage, which had once seemed harmless fun, with insidious sexual inversion.

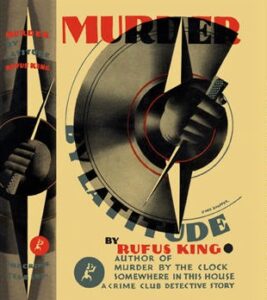

Rufus Frederick King (1893-1966) and Clifford Burrowes Orr (1899-1951), two gay male American authors of Golden Age detective fiction, were closely connected with college theatricals during this era, King in the years immediately preceding World War One, Orr in the years immediately following the conflict. As a member of the Yale Dramatic Association, the blondly attractive and ebullient Rufus King had such a flair for the feminine that he was dubbed the “Queen of the Yale Dramat,” while the sharp-featured and sardonic Clifford Orr, a member of the Dartmouth Players, wrote books and lyrics for musicals that provided opportunities for his fellow players, including his roommate, to shine on stage as women. Rufus King went on to become one of the most popular American mystery writers of the Thirties and Forties, unabashedly revealing in his crime fiction–particularly his stunning tour de force Murder by Latitude (1930)—ample evidence of his “bad, bad past” on the college stage; while intimations of a grimmer kind of queerness are evident in Clifford Orr’s life and in his two Golden Age detective novels, The Dartmouth Murders (1929) and The Wailing Rock Murders (1932).

Rufus King: Queen of the Yale Dramat

In overlapping years shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, future prominent American songwriter Cole Albert Porter, born on June 9, 1891, and future prominent American crime writer Rufus Frederick King, born on January 3, 1893, both of whom were the only children of wealthy parents, attended Yale University. The families of the two young men desired that their promising scions become respectable lawyers, but their careers did not pan out that way. While students at Yale, both Porter and King took to musicals and became key members—indeed, in their respective senior years, presidents—of the Yale Dramatic Association, popularly known as the Yale Dramat. King also was a member of the Elizabethan Club, dedicated to conversation, tea and literature, and, along with Porter, was one of the Pundits, a group of ten “devoutly literary” students who met weekly for dinner and lectures at the home of famed English professor William Lyon Phelps (a great fan of detective fiction, by the by).

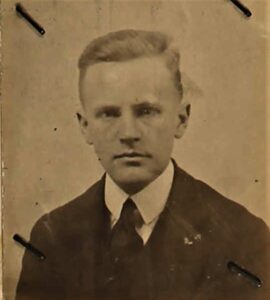

When Rufus King first came to Yale, the slightly older Cole Porter already was writing musical plays for the Dramat. In 5’7”, blond-haired, blue-eyed, delicately-featured “Rufe,” as he was known to his friends, the dark-haired, keen-eyed Porter immediately descried a new drag star. Among the same-sex Dramat membership Rufe excelled at playing women’s parts, and he immediately became one of the organization’s leading attractions. Testifying to the young man’s prominence within the group, another member once penned the following envious couplet: “Little Rufe King couldn’t teach me a thing/I’m the Queen of the Yale Dramat.”

When Rufus King first came to Yale, the slightly older Cole Porter already was writing musical plays for the Dramat. In 5’7”, blond-haired, blue-eyed, delicately-featured “Rufe,” as he was known to his friends, the dark-haired, keen-eyed Porter immediately descried a new drag star. Among the same-sex Dramat membership Rufe excelled at playing women’s parts, and he immediately became one of the organization’s leading attractions. Testifying to the young man’s prominence within the group, another member once penned the following envious couplet: “Little Rufe King couldn’t teach me a thing/I’m the Queen of the Yale Dramat.”

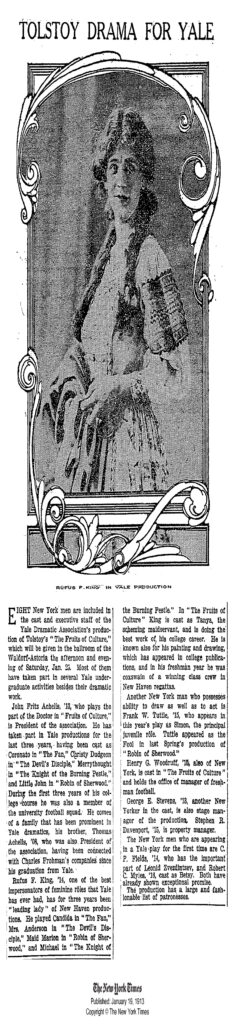

The best known Cole Porter play in which Rufe King starred was And the Villain Still Pursued Her (1912), a send-up of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and similar nineteenth-century melodramas. Another Yale man, the future Oscar-nominated actor Edgar Montillian “Monty” Woolley, played the villain, while little Rufe King, then just nineteen, took the heroine’s part, singing the ditty “The Lovely Heroine.” (“Oh gee! It’s heaven to be the lovely heroine/All the men woo me/And try to undo me/But that’s not my line.”) Quite the diva, King had other major star turns in Porter’s college musicals, performing additional camp numbers like “Oh What a Lovely Princess” (“Years have I waited for someone adorable/So far my luck is deplorable”) and “The Prep School Widow” (“I find that school boys offer more/than many a college sophomore”); yet he also distinguished himself in drag roles in non-musical plays, such as Leo Tolstoy’s The Fruits of Culture (Tanya), Carlo Goldoni’s The Fan (Candida), George Bernard Shaw’s The Devil’s Disciple (Mrs. Anderson) and Jack Randall Crawford’s Robin of Sherwood (Maid Marian, of course).

In a 1913 review of the Dramat’s staging of The Fruits of Culture, the New York Times lauded King as “one of the best impersonators of feminine roles that Yale has ever had” and divulged that his “impersonations have caused a good deal of favorable comment.” Other northern newspapers carried King’s arresting photo in the part of the maidservant Tanya at the head of the article, along with the caption “Mashers Beware: This Yale Thespian Is Husky.” Readers were assured that this husky, cross-dressing thespian did not camp it up on stage, having scrupulously taken pains “to imitate the voice and to wear the clothes of a woman,” as well as “walk, sit, dispose of the hands and even control the eyes properly.”

In another newspaper notice, for The Devil’s Disciple, it was divulged that “Rufus King, the leading lady of the company, will be gorgeously attired. The masters of the wardrobe announce that he will wear one stunning gown of blue and two morning robes of a lovely violet shade, and that his makeup and his costuming will be up to the Julian Eltinge standard [referencing a nationally famous female impersonator, then performing the title role in the hit play The Fascinating Widow].” The Dramat took Disciple on the road, touring several cities in the northeast with King as Mrs. Anderson and Monty Wooley as General Burgoyne, but both of these able thespians were upstaged with nearly tragic consequences in Buffalo, New York when Irving Goodspeed Beebe, playing the title role (at 6’1” and 180 pounds he was rather too hefty for female parts), was almost choked to death during the play’s hanging scene. To prevent his actual strangulation, Beebe had to be physically held up until the knot could be slackened. Now, there you have a murder scenario for a crime novelist! (After having survived a stint of professional acting, Irving Beebe, by the by, in 1930 was living in New York with his partner John C. Milne and engaged in the antique business. Thirteen years later, Beebe, now fifty-five, finally settled down to marriage, after “the simplest of weddings,” with the widow of wealthy tobacco family scion Louis Lasher Lorillard.)

During his senior year in 1914, little Rufe King gracefully relinquished female parts to younger, up-and-coming lads, strictly playing men for the remainder of his time at Yale. He planned to enroll in Columbia Law School, but abruptly he charted another, for more unusual, course. A natural athlete who had always loved participating in water sports (during his freshman year he had served as coxswain of Yale’s crew team), King upon graduation spent a couple of vagabond years at sea as a shipboard wireless operator, enjoying a “romantic life of rolling ships and strange ports,” and afterward worked a year in a Paterson, New Jersey silk mill.

In 1916 King, then twenty-three years old, enlisted in the Squadron A Calvary, a unit of the New York State National Guard composed of “many of the foremost young society men of New York,” and he served in the Mexican Expedition against the forces of revolutionary leader Francisco “Pancho” Villa. When, with American entry into the Great War in 1918, his cavalry unit was reorganized as the 105th Field Artillery, King served overseas in Europe with Battery A, in this capacity seeing continuous martial action and rising to the rank of 1st Lieutenant. During the war King performed with remarkable heroism in the Meuse-Argonne offensive, proving that there is nothing fiercer than an old drag queen. For “conspicuous gallantry in action during the operations of the 105th Field Artillery in the vicinity of Bois de Sachet, France, October 5, 1918” he was awarded the Silver Star Medal. After having been “suddenly placed in command of his battery by the evacuation of his Captain,” the award citation explains, Lieutenant King “displayed great initiative, energy and unusual military ability in placing his battery in position, establishing communication and liaison and opening effective fire on enemy positions.”

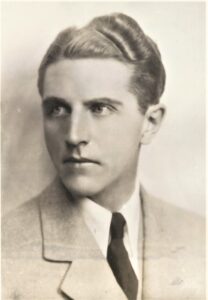

After the end of hostilities in Europe, little Rufe King, now a heroic war veteran, for a time joined the maritime division of the New York police, but by the mid-1920s he had settled down to make a career for himself as a novelist. Within a few years the fledgling author hit the bigtime as a crime writer with the publication of the mysteries Murder by the Clock (1929) and Murder by Latitude (1930), and he became one of the most popular and acclaimed American detective novelists of the Thirties and Forties. Choctaw mystery writer Todd Downing proclaimed King his favorite crime writer, surpassing even Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen and John Dickson Carr, while none other than gangster John Dillinger had with him a copy of one of King’s mysteries, Murder on the Yacht (1932), during his 1934 shoot-out with FBI agents at the Little Bohemia Lodge in Wisconsin. If mysteries could appeal to tired businessmen, clergymen and politicians, why not desperate, holed-up gangsters?

Rufus King’s wealthy New York physician father, Thomas Armstrong King, passed away at the age of sixty-two in 1928, leaving his son a substantial inheritance, suitably managed by a responsible trustee. “Dr. King somehow knew that Rufus needed his money looked after,” this trustee’s daughter later recalled in a blog comment posted under the name janec. Throughout the Thirties and Forties King resided at a Manhattan apartment and at the upstate New York King family home at the village of Rouses Point, located on Lake Champlain, less than a mile south of the US-Canadian border. Frequently he wintered in southern Florida, often in the company of his mother, Amelia Sarony Lambert King, with whom he had a very close relationship. Janec recalls that Amelia King was her gifted son’s most trusted reader: “She was given the manuscript half-way through” and “[i]f she could guess who the murderer was, he re-wrote.” Although the trustee personally “found Rufus rather alarming,” both his wife and daughter hit it off with the author in a big way. “I adored Rufus,” janec recalls, “he was an enchanting person….my mother and Rufus laughed gaily and understood each other. When asked, he presented her a copy of [Museum Piece No. 13, one of his mystery novels], inscribed. Knowing him, my mother said, ‘Now Rufus, please write something I can show to my dignified friends.’ Upon which he wrote, ‘For Jane, to show her dignified friends. With love to her, and nuts to them.’”

Rufus King’s wealthy New York physician father, Thomas Armstrong King, passed away at the age of sixty-two in 1928, leaving his son a substantial inheritance, suitably managed by a responsible trustee. “Dr. King somehow knew that Rufus needed his money looked after,” this trustee’s daughter later recalled in a blog comment posted under the name janec. Throughout the Thirties and Forties King resided at a Manhattan apartment and at the upstate New York King family home at the village of Rouses Point, located on Lake Champlain, less than a mile south of the US-Canadian border. Frequently he wintered in southern Florida, often in the company of his mother, Amelia Sarony Lambert King, with whom he had a very close relationship. Janec recalls that Amelia King was her gifted son’s most trusted reader: “She was given the manuscript half-way through” and “[i]f she could guess who the murderer was, he re-wrote.” Although the trustee personally “found Rufus rather alarming,” both his wife and daughter hit it off with the author in a big way. “I adored Rufus,” janec recalls, “he was an enchanting person….my mother and Rufus laughed gaily and understood each other. When asked, he presented her a copy of [Museum Piece No. 13, one of his mystery novels], inscribed. Knowing him, my mother said, ‘Now Rufus, please write something I can show to my dignified friends.’ Upon which he wrote, ‘For Jane, to show her dignified friends. With love to her, and nuts to them.’”

Although his father came of old and straight-pathed New England stock, King’s beloved mother was a French Canadian Catholic by upbringing, a daughter of Theodore Sarony Lambert, a photographer (he patented “Lambertype”) and nephew of Napoleon Sarony (1821-1896), successor to Matthew Brady as the most famous photographer in the United States. Although considered eccentric, Sarony—whose celebrity subjects included writers Mark Twain and Oscar Wilde, actresses Sarah Bernhardt and Lillian Russell, inventor Nikola Tesla, soldier William T. Sherman and bodybuilder Eugene Sandow—had immense talent and a genius for self-promotion, especially in the theatrical world:

His flair for odd costumes, along with his flowing beard and mustache, made him an object of great wonder and attention, especially among artists and bohemians of all stripes. He often delighted in strolling down Broadway in an astrakhan cap, a calfskin vest with the hairy side out, and trousers tucked into highly polished cavalry boots….but it was not his odd appearance nor the real Egyptian mummy that stood guard by the door to his studio which made him society’s favorite. Sarony was particularly good at shooting theater people….during his career he produced forty thousand photographs of members of the dramatic profession alone.

Perhaps not surprisingly, given their great-uncle’s renown among artistes and theater folk, both Amelia Sarony-Lambert’s brother Thomas and her sister Nora, the latter of whom lived with the Kings for many years, went into the acting profession. Nor is it surprising that stage lights attracted handsome young Rufe.

For years Rufus King was a fixture of the social scene at Rouses Point, writing his novels and keeping up his interest in the stage by performing in and directing such works as an adaptation of W. W. Jacobs’ short story The Monkey’s Paw and his own original crime plays, Invitation to a Murder and the suggestively-titled I Want a Policeman, at the Little Theatre at Plattsburgh, the county seat. In 1932 King told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle that he “prefers the quiet of Rouses Point in which to write his thrillers,” deeming that the “bridge, dogs, gossip and scandal up there among ice, snow, sleet, howling winds, beautiful springs, blissful summers and blustery autumns” fostered his writing. However, after the death of his eighty-two-year-old mother in 1950 and the publication of a final crime novel the next year, King left New York, moving for good to Broward County, Florida. There he enjoyed a life in retirement, writing for Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine occasional pieces of short crime fiction (which he later collected in three published volumes) until his death from a heart attack at the age of seventy-two at his small home in West Park, Florida in 1966. Although a place had been reserved for him in the family vault back at Rouses Point, King’s body was cremated and his ashes scattered over the ocean waters lapping Florida’s Dania Beach. With his demise, memory of King as a mystery writer soon ebbed, despite his onetime popularity. However, during the early years of my blog The Passing Tramp I raved a great deal about King’s crime writing (as did several other bloggers, including Mike Grost and John Norris) and his books have since been reprinted.

The homosexuality of Cole Porter and Monty Woolley, King’s colorful pals from his Yale Dramat days (Wooley remained a lifelong friend), has long been noted in books, yet Rufus Kings’ sexuality, like his life in general, has received little attention. To be sure, King’s publicity material stressed the “quiet bachelor” author’s martial prowess and rugged masculinity. The biographical blurb carried on some of his books reads as follows:

Rufus King has poured into [his series detective] Lieutenant Valcour the result of all his varied experience in adventure and crime detection. Mr. King has been a cavalry man on the Mexican border, an officer in the artillery during the war, where he fought in the battle that swayed back and forth across the Meuse. He admits that he was cited for holding the front line in the Bois de Sachet with two French .75s. He has been a wireless man on freighters, tankers and fruit ships, cruising the seven seas. He has salvaged a ship off Pernambuco and hauled it into port. He has beachcombed along the waterfront of Buenos Aires, has served in the marine division of the New York police, and in general has lived the sort of life which could be expected from the creator of so exciting and glamorous detective as Lieutenant Valcour.

Yet Rufus King’s close affinity with the feminine, both in his drag performances and his personal relationships, suggests on his part a certain queerness, a quality which is also prevalent in his crime fiction, perhaps most strikingly in the second of his pair of breakthrough mysteries: Murder by Latitude (1930), a thrilling tale of a vicious murderer run amok on an ocean liner.

Murder by Latitude is one of a number of Rufus King crime novels with maritime settings, other notable examples being Murder on a Yacht (1932) and The Lesser Antilles Case (1934), all of which take advantage of King’s deep familiarity with the life aquatic. In Latitude a ruthless murderer, having already struck once on land, boards the ocean liner Eastern Bay, bound from Bermuda to Halifax, Nova Scotia and thereupon kills again, the victim this time being Mr. Gans, the ship’s wireless operator (a post, it will be recalled, which King had once himself held as a young man). This slaying prevents the Eastern Bay from receiving messages from the New York police, who now have a description of the murderer to send to Lieutenant Valcour, King’s stylish series sleuth, already on board the ship in search of the culprit. Now Valcour is left groping in the dark, pursuing a murderer with a mysterious–and quite deadly–agenda to fulfill.

In Murder by Latitude King fashioned an ingenious and suspenseful detective novel, peopling it with an exceptionally intriguing cast of characters, including both crew and passengers. Among the crew, there is Mr. Gans, only briefly glimpsed in the novel before his demise, and his devoted friend, young Swithers, who when questioned by Lt. Valcour has difficulty concealing the misery he feels over the cruel loss of his intimate companion:

“…I was with him [Gans] in his shack up to two bells.”

“Talking?”

“Talking.”

….

“About anything special?”

“Just a lot of bull, sir.”

“How did he seem?”

“Seem?”

“Yes, was he natural—not nervous, or depressed, or ill or anything?”

“Just natural, sir. We were”–young Swithers, because of a nasty thick feeling that was bothering his throat, found a momentary difficulty in pronouncing the words—“just talking. Same as usual.”

“And when you left him at nine o’clock he was quite all right?”

“Yes.” Monosyllables were easiest.

Lt. Valcour and another character, the sophisticated and sardonic Mr. Dumarque, reference the classical Damon and Pythias legend at one point in the novel, albeit with a cynical twist:

“There should be no such thing, Mr. Valcour, as friendship. It is nothing but an institution for the coupling of compatible bores with whom the rest of the world has grown fatigued.”

“I’m inclined to agree with you. When one thinks of Damon and Pythias—”

“Let us not.” Mr. Dumarque’s eyes shot fleetingly toward heaven. “One dreads to think on what subjects they conversed after the first six months.”

Then there are the passengers, including certainly Mr. Dumarque, a dandyish, epigram-tossing aesthete, but most strikingly of all the wealthy, middle-aged, much-married Mrs. Poole, a man catcher who harpoons—Valcour’s word—younger men as husbands with steady determination and the skill of long practice. Her latest handsome catch, Ted Poole, throughout the novel is objectified through the eyes of his admiring and acquisitive spouse, as in a passage which commences when the pair is lounging on deck chairs and Mrs. Poole turns to look at Ted, thinking, “It was a pity he had his clothes on….”

In an erotic reverie Mrs. Poole imagines

a tropics filled with Teds, as she had first seen him: flat on his back on the hot pinkish sands of Bermuda’s Coral Beach, very young and wiggling all though his smooth brown hardness, wiggling from sheer pleasure of the drenching, burning sun which was offsetting the chill sea breeze, strong fingers scooping up pink gold and pouring it in lazy rivulets on bronze, his head rising like a turtle’s, and brown eyes staring at her from above sienna cheeks.

“I’ve only got two days left to get burned in,” he had said.

Such explicit expression in a Golden Age detective novel of sexual desire for a male body is unusual, especially in this implicitly homoerotic form, with the female character likely serving as a conduit for the male author’s own feelings. King also eroticizes a later scene in the novel in which Ted, clad only in his underwear, is murdered while shaving, shortly after having performed what he facetiously terms the “six famous poses of the Perfect Athlete.” When Popular Library issued Murder by Latitude in a paperback edition in 1950, it depicted on the cover the scene in the novel where Mrs. Poole dissolves into hysterics over Ted’s corpse, but with one significant alteration: it became a now much younger Mrs. Poole who is dishabille, not the slain Ted–the objectification of the female, not the male, being the name of the game with Fifties mass market paperbacks.

By the end of the novel, the resilient Mrs. Poole, having rebounded emotionally, already is on the hunt for Ted’s replacement. She finds a highly plausible candidate for marriage in the form of a virile young coast guard: “She smiled lazily…and wondered exactly how broad it was—that chocolate-colored neck which pillared above a spotlessly white sweat shirt.” Mrs. Poole truly calls to mind the youth-vamping Cole Porter character which Rufe King had played nearly two decades earlier: the prep school widow, who finds that “school boys offer more/than many a college sophomore.”

[SPOILER WARNING: THE SOLUTION TO THE NOVEL IS REVEALED BELOW] Yet even more remarkable than Mrs. Poole is the gender-bending murderer: a “girlishly pretty” male passenger, who, we learn in a bizarre back story, was raised as a female for four years (from the ages of five to nine), in order to conform with a young Mrs. Poole’s capricious desire to have a daughter “to play with” rather than a son. “[T]here is no masquerade in this whole big world more tragic than one of sex,” intones Mr. Dumarque when he learns the truth from Lt. Valcour. Rufus King, a master-mistress of sexual masquerade, could not have been more in his element as a crime writer than he was when he wrote Murder by Latitude. [END SPOILER WARNING]

Clifford Orr: An Air of Ruined Insouciance

Four years after Rufus King graduated from Yale in 1914, future mystery author Clifford Burrowes Orr, a native of Portland, Maine born on November 19, 1899, matriculated at Dartmouth College, where, like King, he became enmeshed in the world of college musicals. However, the thin, 5’9”, sharp-featured, ginger-haired “Kip” Orr, as he was known, did not himself perform in any musicals, confining his talents, rather, to writing books and song lyrics. Orr’s college drama group, the Dartmouth Players, relied, like the Yale Dramatic Society, on young men to take the women’s parts. Rise, Please!, a mock marital melodrama with book and lyrics by Orr which premiered at the Dartmouth Players’ Winter Carnival on February 10, 1921, tells the story of young Jerry and Jean, whose impending nuptials are abruptly menaced by the appearance of Gertie Purell, a lady of questionable repute with whom the unfortunate Jerry has had a certain prior familiarity. After lamenting, in Orr’s song “A Bad, Bad Past,” of the steep price to be paid for youthful indiscretions (“For every girl that you have known/If you have seen her once alone/She’ll trail you/And nail you.”), poor Jerry does away with himself at the end of Act One. Act Two opens with the descent of a flock of newspapermen, singing that they scent “Scandal”: “Please tell us the facts, sir./We’re sure you won’t object./His life was wrecked and we suspect/Some scandal!”

[In the Twenties real-life fear of sexual indiscretions and public scandal struck at the heart of the Dartmouth Players, including very close to Kip Orr…Stage laughter aside, in the Twenties real-life fear of sexual indiscretions and public scandal struck at the heart of the Dartmouth Players, including very close to Kip Orr, who always seemed to be there, at least on the periphery, when something happened. Three days before Rise, Please! was to premier, James Harvie Dew Zuckerman, one of Orr’s closest Dartmouth friends (the two young men roomed together their senior year and additionally lived together for a year after leaving college), had been called upon to step in and save the day when the young man originally cast to play Jerry’s bride was taken ill with appendicitis. Happily for the Players, Harvie Zuckerman had experience with women’s parts, having played the female lead in the 1919 Dartmouth Players prom show, Oh, Doctor! Less happily for Zuckerman personally, about a month after his two performances as Jean at the Winter Carnival, he visited the President of Dartmouth, Ernest Martin Hopkins, seeking Hopkins’ help in dealing with certain disturbing feelings he was having.

President Hopkins promptly steered the young man to Dr. Charles Bancroft, “the most prestigious psychiatrist” in the state, sending ahead of Zuckerman a letter delicately explaining the nature of the prospective patient’s problem:

I do not think that in his case abnormality has gone to any detrimental extent as yet and I would not willingly urge the boy into anything that would make him feel that he is an exception to the ordinary run of men but I do feel very strongly that he needs to be helped on reversing certain tendencies of his….

Sometime I want to talk with some of your authorities on mental hygiene in regard to the general problem of whether playing girls’ parts in the dramatic performances makes a man effeminate or whether being effeminate qualifies him for playing girls’ parts. I am considered, among the dramatic group, as being unduly concerned on the question and if so I want to get over it.

The fact is, however, that we have had a distinct tendency among a considerable number of the men who have played the so-called leads in girl characters to develop exotic and unnatural instincts which are thoroughly out of keeping with what the College means to stand for.

In one case, three years ago, the boy wandered off from Hanover and safeguarded the College reputation to the extent that he committed suicide in New York rather than here, but the underlying fact was that his affection for one of his dramatic club associates was not only unappreciated but was rebuffed. We have had one other case in which I would a good deal rather the boy have committed suicide.

With Zuckerman there is nothing of this seriousness at all and as a matter of fact it is somewhat on the basis of his own recognition of conditions that I am bespeaking your help….

We have been remarkably free from the deviations from normal and the sex aberrations which have been so serious a condition in many of the colleges of the country and we have taken every possible precaution to watch and guard against any outbreak of this. I hope that we may be spared what many of the others have had to experience….

During the previous year officials at Harvard University had formed a co-called “Secret Court” to root out those at the school who were suspected of what Hopkins had termed “exotic and unnatural instincts,” with the result that seven students were expelled (one of whom shortly afterward committed suicide). Harvard tried to keep its sexual inquisition from becoming public knowledge, but it seems likely that the Dartmouth president heard something about it. In any event, despite Hopkins’ fervently expressed hope that Dartmouth be spared the “sex aberrations which have been so serious a condition in many of the colleges of the country,” the plague of aberrancy struck Dartmouth only a few years later, the locus of contagion once again being found amid the Dartmouth Players.

Among other things Harvie Zuckerman was advised, during his consultation with Dr. Bancroft, Superintendent of the New Hampshire State Asylum and Secretary of the National Committee for Mental Hygiene, to desist from impersonating women, to play tennis regularly and to cultivate a scientific hobby, such as ornithology or botany. Whether Zuckerman took up tennis and birdwatching in a big way is unknown, but he did stop playing female parts in college plays. On campus he began meeting regularly with a minister and gradually faded from active participation in the Dartmouth Players. (Later in life he converted to Protestantism, became a minister himself, wed and fathered several children.) Kip Orr, on the other hand, kept writing plays for the group and even became the Players’ president during his senior year. He later told President Hopkins that a year had elapsed before he learned of Zuckerman’s personal crisis.

In 1923, a year after Orr has completed his Dartmouth coursework, star Dartmouth Players Ralph Garfield Jones and William McKay Patterson—Jones had played villainess Gertie Purell in Rise, Please! and Patterson had taken the role of the bride’s sister—bought, along with several other individuals, a house located across the Connecticut River from the college, in the hamlet of Beaver Meadow, Vermont. There the group played host to other young men currently or formerly associated with the Dartmouth Players, including Kip Orr. By 1925 the house at Beaver Meadow had become a center of sinister speculation, with President Hopkins concluding from dark stories he had heard that “going to or visiting in the house at Beaver Meadow…was prima facie evidence of undesirability.” As Nicholas Syrett has more bluntly put it in his essay “The Boys at Beaver Meadow,” in this house “an all-male group of Dartmouth students and recent graduates…had parties, stayed up late, drank alcohol, and had sex. With each other.” Dartmouth responded to the shocking situation by expelling one student visitor to the house, while Jones and Patterson, who had graduated the previous year, were requested to resign from their college fraternity, to which request they hastily complied. By the next year the Players were importing women to play female parts in their plays and by 1929, men in drag had been banished entirely from the stage at Dartmouth.

In 1923, a year after Orr has completed his Dartmouth coursework, star Dartmouth Players Ralph Garfield Jones and William McKay Patterson—Jones had played villainess Gertie Purell in Rise, Please! and Patterson had taken the role of the bride’s sister—bought, along with several other individuals, a house located across the Connecticut River from the college, in the hamlet of Beaver Meadow, Vermont. There the group played host to other young men currently or formerly associated with the Dartmouth Players, including Kip Orr. By 1925 the house at Beaver Meadow had become a center of sinister speculation, with President Hopkins concluding from dark stories he had heard that “going to or visiting in the house at Beaver Meadow…was prima facie evidence of undesirability.” As Nicholas Syrett has more bluntly put it in his essay “The Boys at Beaver Meadow,” in this house “an all-male group of Dartmouth students and recent graduates…had parties, stayed up late, drank alcohol, and had sex. With each other.” Dartmouth responded to the shocking situation by expelling one student visitor to the house, while Jones and Patterson, who had graduated the previous year, were requested to resign from their college fraternity, to which request they hastily complied. By the next year the Players were importing women to play female parts in their plays and by 1929, men in drag had been banished entirely from the stage at Dartmouth.

After leaving the college in 1922, Orr, unscathed by the Beaver Meadow affair, spent three years working at the Boston Evening Transcript, then for another three years was successively employed as publicity manager for publisher Robert M. McBride and as manager of publisher Doubleday, Doran’s Wall Street bookshop. Upon deciding in 1928 to try making his living as a freelance writer, Orr that summer penned most of his first novel, The Dartmouth Murders, while lazing on Ogunquit Beach, Maine, a locale which had become a haven for bohemians and artists. Ogunquit at this time has been characterized as having been a “place to escape the sexual and gender strictures of middle-class America—if only for a few weeks in the summer.” Such an escape, as we shall see, would have proved welcome for Orr.

Clifford Orr’s novel was accepted by the American publisher Farrar & Rinehart and issued in 1929 to good reviews, encouraging the young author to compose another mystery, The Wailing Rock Murders, which was published in 1932 by Farrar & Rinehart to even better reviews than his first novel. The rising crime writer was said to have a third mystery, The Cornell Murders, in preparation, but it never appeared; and, indeed, no more detective fiction was ever to come forth from Orr’s hand, although a film version of The Dartmouth Murders, entitled A Shot in the Dark, was released by a poverty row studio in 1935. (It starred a hunky Charles Starrett, a former Dartmouth football player.)

Orr became a features writer for the New Yorker, in the two decades between 1932 and his death in 1951 publishing over 400 columns, many of them for the popular “Talk of the Town” section. At the New Yorker Orr also was tasked with answering letters to the editor, including those from the many people puzzled and/or outraged by the ending of Shirley Jackson’s famous story “The Lottery,” originally published in the magazine in 1948. Although Orr’s crime writing and journalism largely was forgotten after his death, in recent years his name has resurfaced, on account of his connection with the Beaver Meadow affair, in studies of college homosexuality in the 1920s.

During his lifetime Clifford Orr unquestionably traveled a far piece from his relatively simple turn-of-the-century origins in Portland Maine. Orr’s father as a younger man had possessed writing ambitions, but he gave them up when he married, becoming an advertising agent for a mercantile establishment, while his paternal grandfather had been “one of the most upright…sea captains on the Maine coast,” with his wife “very faithful members of the Baptist church” and in his own right a “noble member of the Sons of Temperance.” Kip Orr had once wryly contrasted himself with his sea captain grandfather, noting that “I am seasick at the sight of a canoe,” and doubtlessly he had been involved in activities at Dartmouth at which the pious old man would very much have looked askance. Orr was in fact gay, as his college association with the Dartmouth Players and the boys at Beaver Meadow have suggested to analysts of the Beaver Meadow affair. Certainly the lyrics to Orr’s song “A Bad, Bad Past,” warbled by a young man who on stage has just wed another young man in drag (played, in the event, by Orr’s roommate), suggest a winking acknowledgment of some queer skeletons in the closet (e.g., “There’s nothing you can hide/That’s so/I know/I’ve often tried.)

At the New Yorker, Orr, who lived in Greenwich Village, had a reputation as a waspish, embittered homosexual and confirmed alcoholic. In a coded 1934 article in the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine, Francis H. Horan reported visiting Kip at the New Yorker and described him, “like all other humorists we had ever known,” as a “very melancholy, sad-looking young man,” with, around his eyes, the “minute shadows of bad lines that he had kept out of the New Yorker.” After showing him around the premises Orr “left the office with us,” Horan reported, adding wryly: “In his professional capacity of reporter he had to go to a class at the newly founded College for Bartenders.”

In his controversial 1975 memoir, Here at the New Yorker, Orr’s work colleague Brendan Gill painted a poignant picture of Kip in the 1940s, no longer laughing at life:

He had been a brilliant undergraduate at Dartmouth and had written a successful mystery novel about the college….Alcoholic and homosexual, Kip took terrible chances with his life, and it became a wonder that he wasn’t murdered; more than once he was rolled, beaten up, and left for dead in some dirty doorway in the Village, and yet he survived to die sadly in the small college town where, for a little while, he had known good fortune. When I first encountered him…his reddish pompadour was going grey and his large light-green eyes had lids shocking in their rolled-back redness. He had an air about him of ruined insouciance, and this was heightened by the fact that he wore good-looking, old-fashioned tweeds and English brogans with the exceptionally thick, light-colored crepe soles that were in vogue in the twenties. Thanks to those soles, Kip was able to steal up behind one in the corridors and suddenly whisper some abrupt, catty remark, or offer the latest gossip about some fresh office disaster, and one was more startled by the fact of his presence at one’s ear than by anything he said….For lunch Orr would drink a series of sweet Manhattans, signaling so discreetly to the waitress for a second, third, and fourth that in my earliest acquaintance with him I supposed him always to be sipping daintily at his first.

Gill vividly recalled Kip—who back in 1929 had composed customarily ironic lyrics to the popular song “I May Be Wrong (But I think You’re Wonderful)” (sung by Doris Day in the 1950 Kirk Douglas film Young Man with a Horn)—at cocktail parties when the piano was played, standing “at one end of the piano, drink in hand, listening raptly. As the evening wore on, his eyes would grow more and more watery, and it was odd and touching to see him, as happy in those moments as he would ever be, apparently dissolved in tears.” After a three-and-a-half month stay at a nursing home in Grafton County, New Hampshire, Orr died in 1951, five weeks shy of his fifty-second birthday. The cause of the writer’s death was listed as malnutrition induced by cancer of the pharynx. At his death he was also suffering from alcoholic encephalopathy, or brain injury stemming from alcohol abuse.

Something of Orr’s evident unhappiness—his sense, perhaps, of perennially being an outside observer of life—comes through in his pair of detective novels, deadly serious affairs in which the sardonic gaiety of his song lyrics is entirely absent. Orr dedicated both of his detective novels to Dartmouth friends, The Dartmouth Murders to tall, slender, black-haired, blue-eyed Franklin McDuffee, Dartmouth ’21, a Rhodes scholar, prize-winning poet and Dartmouth English professor best known today for having written lyrics to the popular college song “Dartmouth Undying,” and The Wailing Rock Murders to Bill North (“who hates this sort of thing”), who had been one of the co-owners of the house in Beaver Meadow and later was employed as a teacher at a boys’ school. Like Orr himself, both North and McDuffee never married. A year older than Orr, McDuffee at the age of forty-one committed suicide at Dartmouth by inhaling automobile exhaust fumes in his garage. Friends avowed that for several weeks he had been suffering from “melancholia.”

The Dartmouth Murders, the book Kip Orr dedicated to Franklin McDuffee, ironically opens with a suicide on campus, though in this case the purported suicide actually proves to be murder. In the first chapter of the novel Dartmouth student Byron Coates is discovered dead, hanging by his neck from the rope ladder fire escape suspended outside his locked dormitory bedroom in real life North Massachusetts Hall, where Orr himself had resided. After Byron’s death is established to have resulted not from hanging but rather from a particularly nasty form of foul play, Kenneth Harris, the dead boy’s roommate and best friend, and Ken’s officious father, an attorney and occasional detective novelist, act as an investigative team in the affair, somewhat in the manner of Ellery Queen and his police inspector parent, who debuted the same year in The Roman Hat Mystery, although in The Dartmouth Murders these roles are reversed, with Ken Harris functioning as the novel’s Watson figure and retrospective narrator.

Throughout The Dartmouth Murders, Ken Harris evinces little interest in Byron’s sister, Jean (she carries the same name as the bride in Rise, Please!), who is visiting from Vassar for the weekend. Jean “was handed over to me as a companion,” notes Ken neutrally. “I was neither pleased nor displeased. She was, I thought, a nice girl, quite good-looking in a dark, slim way, but a little strange.” The author soon transfers Jean as a romantic interest to another young male character in the novel. Ken musters much more enthusiasm for the late Byron, whose name of course recalls that of that great gay icon, the bisexual Romantic poet Lord Bryon.

The author described Ken’s friendship with Byron in what seems something of a semi-autobiographical passage:

We were good companions, careless friends, and happy enemies when anything small enough arose to fight about. His claim to undergraduate fame lay in his really excellent baritone voice. Mine lay in a facility with the piano and an ability, after a fashion, to write dancy tunes for the annual music shows. He was more of an athlete than I and dabbled a bit as a sophomore in both track and swimming, and he was also more studious, though his grades almost always fell slightly short of mine. Mine was the quicker wit, his the greater doggedness. We took to each other’s friends as easily as we did to each other’s clothes.

Ken emotionally describes the scene when he is asked to formally identify his dead friend’s body: “I leaned forward and looked….Byron was beautiful….The tears welled in my eyes and I was glad that Father turned at once and made for the door.” Recalling the morning of the day of Byron’s death, he imparts that his friend had implored him, “If I die, for heaven’s sake don’t ship my letters home to Mother without sorting them first”—a suggestive request when one considers that it was an incriminating letter discovered after the suicide of a Harvard student which kindled that school’s anti-queer inquisition in 1920. Obsession and sexual secrets play a great role in The Dartmouth Murders, although they concern matters other than homosexuality. In passing we learn that Byron was a reader of the English sexologist Havelock Ellis, a pioneer in the study of same-sex attraction, but Byron’s peculiar difficulty seems to have arisen not from homosexuality but rather from a mother fixation. Ken’s feelings for Byron certainly leave room for speculation, however.

In form The Dartmouth Murders is a competently executed but conventional detective novel that in its day garnered attention, including its eventual film adaptation, for the novelty of its college setting and the fact that a real-life murder had occurred on the Dartmouth campus nearly a decade earlier. (Prosaically one student had shot and killed another in a dispute over bootleg alcohol.) Orr’s second and final detective novel, The Wailing Rock Murders, is an altogether more remarkable affair. “Too good a book may undo a writer as well as too bad a one,” wrote English author and crime fiction reviewer Charles Williams in his notice of the novel, “and what Mr. Orr is going to do for his next climax I cannot think.” Set on the rocky Maine cliffs above Ogunquit Beach, where Orr had written his debut mystery, The Wailing Rock Murders bears considerable similarity to the “old dark house” thriller popularized at the time though books and such hit films as The Bat (1926), The Cat and the Canary (1927) and, of course, The Old Dark House (1932), as well as to the horror-infused detective fiction of John Dickson Carr, although at the time of the publication of Orr’s second novel Carr had not yet hit his stride as a mystery writer. Acknowledged as the Golden Age master of the locked room mystery, Carr was an adept at atmospherics, producing such spine-chilling mystery classics as The Three Coffins (1935), The Burning Court (1937), The Crooked Hinge (1938) and He Who Whispers (1946). As a detective novel Orr’s second mystery does not rise to the exalted level of these Carr classics, yet it offers mystery fans a superbly shuddery and suspenseful read. Much of the plot of the well-regarded 1946 noir film So Dark the Night appears to have been adapted from The Wailing Rock Murders, though unfortunately without acknowledgment of Clifford Orr.

In form The Dartmouth Murders is a competently executed but conventional detective novel that in its day garnered attention, including its eventual film adaptation, for the novelty of its college setting and the fact that a real-life murder had occurred on the Dartmouth campus nearly a decade earlier. (Prosaically one student had shot and killed another in a dispute over bootleg alcohol.) Orr’s second and final detective novel, The Wailing Rock Murders, is an altogether more remarkable affair. “Too good a book may undo a writer as well as too bad a one,” wrote English author and crime fiction reviewer Charles Williams in his notice of the novel, “and what Mr. Orr is going to do for his next climax I cannot think.” Set on the rocky Maine cliffs above Ogunquit Beach, where Orr had written his debut mystery, The Wailing Rock Murders bears considerable similarity to the “old dark house” thriller popularized at the time though books and such hit films as The Bat (1926), The Cat and the Canary (1927) and, of course, The Old Dark House (1932), as well as to the horror-infused detective fiction of John Dickson Carr, although at the time of the publication of Orr’s second novel Carr had not yet hit his stride as a mystery writer. Acknowledged as the Golden Age master of the locked room mystery, Carr was an adept at atmospherics, producing such spine-chilling mystery classics as The Three Coffins (1935), The Burning Court (1937), The Crooked Hinge (1938) and He Who Whispers (1946). As a detective novel Orr’s second mystery does not rise to the exalted level of these Carr classics, yet it offers mystery fans a superbly shuddery and suspenseful read. Much of the plot of the well-regarded 1946 noir film So Dark the Night appears to have been adapted from The Wailing Rock Murders, though unfortunately without acknowledgment of Clifford Orr.

The events of The Wailing Rock Murders take place over one hagridden evening and morning on an isolated stretch of Maine coast, where are found a whistling rock whose sound foretells of death and two identical neighboring cliffside houses, Victorian monstrosities described with distaste by the narrator of the novel, Spaton Meech, who shares the rationalist disdain, so typical of Golden Age detective fiction, for the romantic excesses of mid- to late-nineteenth-century architecture. Nearly seventy-six years old, Meech is a sleuth of long and esteemed repute, but in The Wailing Rock Murders he is more a figure of pathos than an archetypal Great Detective, striding confidently and nonchalantly through fictional annals of brilliant crime detection. “I am no writer,” Meech tells us plaintively at the opening of the novel. “But I have no Watson to write for me. I have never had a Watson, lonely freelance that I have been for so long.” Nor does Meech have the handsome countenance and form of many a gentleman detective, as his nickname, “Spider,” indicates:

They call me “Spider,” and I know why. It is because I am slightly deformed from a spinal twist I received in a fall from a rope-swing when I was only five, and because my arms are very long and hang to my knees, and because my head is large and seems to lie on my chest when I walk, and because (on account of my shape) I prefer to sit cross-legged on tables or on the floor rather than to rest my hump against the unyielding back of a chair….

Naturally I am a bachelor….

Meech explains that this, his latest, most personal and perhaps final investigation, arose after his ward, Garda Lawrence, invited him to a weekend house party at the country mansion of Creamer and Vera Farnol. On the very night of his arrival at the perilously rock-perched Farnol abode, Meech discovered Garda slain in her locked bedroom, her throat “most horribly, most hideously slit.” Before his investigation into Garda’s savage murder is over, two more people will be dead, with every promise of a third death soon to follow—a resolution that is a long way from the “restoration of order” which is said to characterize Golden Age mystery. Indeed, the lack of comfort afforded readers of The Wailing Rock Murders is the most striking aspect of the novel. Meech begins and ends the tale an isolated and sad figure, someone always seen as essentially an outsider and denied a “normal” existence, despite widespread public acclaim for his cleverness. One can sense parallels with the life of the author himself, a “lonely freelance” who, in contrast with Rufus King, never seems to have found contentment in his life, despite the great promise he showed from an early age. “Kip Orr, too, sought death,” claimed Orr’s New Yorker colleague Brendan Gill, just like Franklin McDuffee in real life and Byron Coates in fiction—and, it is implied in the dreadful last line of The Wailing Rock Murders, like Spaton Meech will do as well.