In June of 2022, the Supreme Court struck down a New York law known as The Sullivan Act which made it a felony to carry a concealed weapon without a license. Sullivan, ruled the court, violated the Second Amendment by making it “virtually impossible for most New Yorkers” to possess firearms unless they could demonstrate a specific need to own a gun. Writing the majority opinion for New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen, Justice Clarence Thomas insisted that going forward, gun regulation must be “consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition.” Never mind that the law had been in place for more than a century.

The end of Sullivan might not have surprised the man whose murder inspired it. Journalist and novelist David Graham Phillips had a low opinion of government officials. In 1906, he wrote a series of articles called The Treason of the Senate, in which he accused several senators of being corrupt lackeys of the rich and entitled. “Did you ever think where the millions…that are spent in national, state and local campaigns come from? Who pays the big election expenses of your congressman, of the men you send to the legislature to elect senators? Do you imagine those who foot those huge bills are fools? Don’t you know that they make sure of getting their money back?”

A combative writer, Phillips made enemies, among them Theodore Roosevelt who gave him the title “the man who rakes the muck” (reputedly coining the term “muckraker”). He received abuse, even threats, throughout his career. It did not deter him in the slightest. He was prolific, writing six thousand words a day. “If I were to die tomorrow,” he once said, “I would be six years ahead of the game.”

But in 1910, he started receiving anonymous threats and phone calls he found disturbing enough to report to the police. One note read, “This is your last day.” It was signed with his own name. At 1:30, on January 23rd, 1911, the forty-three-year-old Phillips left his Gramercy Park apartment, intending to pick up his mail at the Princeton Club, which was located on 21st Street, on the northern side of the park. A few steps from the entrance, he was shot six times. He died the following day. Feisty to the end, he said, “I could have won against two bullets, but not six.”

David Graham Phillips wasn’t the only New Yorker to fall victim to gun violence in the century’s first decade. In August of 1910 an aggrieved dock worker shot Mayor William Gaynor through the neck in Hoboken. (He survived but the bullet remained in his throat, killing him three years later.) A boiler maker was shot in John Kerr’s saloon during an argument. On July 4th, the New York Tribune announced, “Joey Buono Shot Again.” In February, John Fredericks (no relation) identified a magician—known in the tabloids as “the insane prestidigitator”—as the man who shot not only him, but two six-year-old boys in the Bronx as well.

But the murder of a novelist in broad daylight in such a genteel neighborhood sparked particular outrage. Working in the coroner’s office. George Petit le Brun saw firsthand the damage guns could do and he sent letters to well-connected New Yorkers, urging them to act. One of Tammany’s more colorful personalities, State Senator “Big Tim” Sullivan saw an opportunity. As a man born in the Five Points who ran the Bowery and Lower East Side, Sullivan knew that cheap guns were plentiful in the city. The citizenry was particularly edgy about young Italian men, all of whom supposedly carried guns with malign intent. Sullivan was a sincere champion of poor immigrants; FDR would later remember, “Tim Sullivan used to say that the America of the future would be made out of the people who had come over in steerage.” Sullivan didn’t dispute that there were criminals with guns in the Bowery; some of his closest friends and business associates were criminals. But, he said, “I want to make it so young thugs in my district will get three years for carrying dangerous weapons instead of getting [the] electric chair a year from now.”

He put forth the Dangerous Weapons Bill, which required New Yorkers to be licensed by the police to if they wished to own guns small enough to be concealed. Sullivan divided “gun toters” into three categories: professional criminals, deranged people, and a third group we easily recognize today. “Young fellows who carry guns around in their pockets all the time not because they are murderers or criminals but because the other fellows do it and they want to be able to protect themselves. [T]hose boys aren’t all bad but…just carrying their guns around makes them itch to use them.”

Then as now, opponents questioned the constitutionality of the bill. Those in districts where guns were manufactured took issue. Others argued that criminals would pay no attention to the rules, leaving law abiding citizens at the mercy of hoodlums. It was also suggested that corrupt police officers in league with Tammany, would plant guns on enterprising fellows whose business wasn’t strictly legal, in order to force them to work with the political machine. Bat Masterson called the law “obnoxious.”

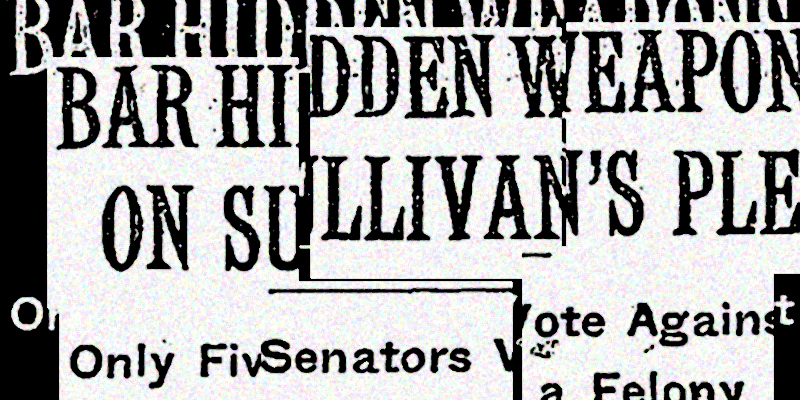

But overall, the act faced little resistance. Only five Senators opposed it in the State Legislature. On August 31, 1911, it became a felony to carry a concealed weapon in New York without a permit. While the cost of a permit was not onerous, the police approved very few applicants, and the number of pistol permits plummeted. The New York Times praised the law as a timely “warning” to the Italian community. Ironically, the first person to be convicted was an immigrant on his way to a job interview who was carrying a gun because he feared being mugged by gangs.

Le Brun and Sullivan’s vision of a city where fewer guns means fewer people dying by gun violence seems to have been realized. New York has one of the lowest rates of gun ownership and according to Pew Research Center, one of the lowest gun death rates per capita in the country, well below other states with more permissive gun laws. Subway shooter Bernhard Goetz was convicted, not because he shot four young men on the subway—one of whom was curled up on the floor—but because he was carrying an unlicensed gun. The men were probably trying to rob him. But Goetz admitted, “My intention was to murder them, to hurt them, to make them suffer as much as possible,” proving that his purpose went well beyond self-defense and indicating—to some—that imposing some kind of standard on those who wish to carry a gun is not a bad idea.

In the Heller ruling, which decided that the Second Amendment did guarantee the individual right to bear arms, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote,” Like most rights, the Second Amendment right is not unlimited. It is not a right to keep and carry any weapon whatsoever in any manner whatsoever and for whatever purpose: For example, concealed weapons prohibitions have been upheld under the Amendment or state analogues. The Court’s opinion should not be taken to cast doubt on longstanding prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, or laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools and government buildings, or laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms. Miller’s holding that the sorts of weapons protected are those ‘in common use at the time; finds support in the historical tradition of prohibiting the carrying of dangerous and unusual weapons.” Justice Scalia seems to have had a different interpretation of historical tradition than the current court.

The impact of Bruen remains to be seen. But the Phillips murder calls to mind another, more recent assault. Phillips was killed because someone took exception to one of his novels. Two months after the Supreme Court overturned Sullivan, Salman Rushdie was attacked by a man in Chautauqua, New York. His assailant was armed with a knife; Rushdie lost the use of one eye and one hand. But he survived. One wonders if that would be so had his attacker been carrying a gun.

***