The despairing silence was broken.

There was someone at the front door, knocking loudly. Helgi got to his feet.

He had been sitting on the sofa with a detective novel, trying to calm himself down before bed by losing himself in a fictional world, but now the peace was over.

He and Bergthóra rented a basement flat in an old house not far from Reykjavík’s Laugardalur area. The whole house was rented out, the flat upstairs occupied by a couple with two children. Apparently the landlord lived overseas. Helgi didn’t get on particularly well with the other tenants, who had a tendency to be rude and interfering, as if their rights took precedence just because they lived in the larger half of the house. As a result, relations between the basement and upstairs were strictly limited and frosty at best.

Helgi was afraid it was the neighbour at the door now, sticking his nose in yet again. But there was another, worse possibility.

He moved reluctantly towards the hall. The sitting room was cosy, the walls lined from floor to ceiling with books—his books; a comfy armchair by the shelves and a decent-sized sofa in front of the television. There were scented candles on the coffee table, but Helgi hadn’t lit them. Not this time. He’d put a record on the stereo, though; a real vinyl one. The stereo was new and connected up to the home cinema, but the records he played were old jazz LPs that had belonged to his father. The heavy banging on the front door broke through the soothing music, wrecking the tranquil atmosphere that had settled over the flat.

Hell, Helgi thought.

He had reached the hall when there was another round of hammering, even louder this time. He drew a sharp breath, then took hold of the handle, pausing briefly to collect himself before he turned the latch and opened the door.

Outside stood a uniformed police officer, a broad-shouldered young man in his mid-twenties, with strong features. He was standing in the glow of the outside light, brightly illuminated in the evening darkness, wearing a look of grim determination, as if he were anticipating a fight. Helgi didn’t recognize him. In the shadows, a little behind him, stood another officer. He seemed more at his ease, judging by his stance, though Helgi couldn’t make out his face.

‘Good evening,’ said the illuminated officer. His voice wasn’t as authoritative as Helgi had been expecting; in fact he thought he detected a faint tremor. Perhaps the determined set of the man’s features was just a ploy to disguise his nerves. Perhaps it was his first shift. ‘Helgi? Helgi Reykdal?’

Although Helgi, now in his early thirties, wasn’t that much older than the man asking his name, he sensed he had the advantage over this young officer.

‘Helgi Reykdal, yes, that’s right. Why, what’s up?’ he asked smoothly, shifting the balance of power slightly.

‘We’ve received—that’s to say . . .’ The young policeman hesitated, as Helgi had guessed he might. ‘A complaint has been received . . .’

Helgi interrupted. ‘A complaint? Who from?’ He wasn’t going to let himself appear flustered.

‘Well, we . . . er, we can’t reveal that.’

‘There’s a bloke upstairs,’ Helgi said, smiling. ‘He’s a bloody nuisance, always complaining. I reckon he must be unhappily married or something. You can’t so much as raise your voice, or, I don’t know, you can’t even turn up the TV, without him banging on the floor with a broom handle. And now I see he’s called the police.’

‘He heard a loud altercation . . .’ The young officer broke off mid-sentence, clearly realizing that he had said too much. ‘That’s to say, we received a complaint . . .’

‘You already mentioned that,’ Helgi said, unfazed.

‘A complaint about a loud disturbance at this address—a quarrel and screaming. More serious than your average row.’

At that moment the other police officer emerged from the shadows, looked Helgi straight in the eye, then took a step closer. ‘You know, I thought the name sounded familiar,’ he said to Helgi.

The moment he got a good look at the man, Helgi recognized him. They had sometimes worked the same shifts in the Reykjavík police last year, though they didn’t actually know each other that well.

‘The name’s Reimar,’ the officer said. ‘Were you just temping with us over the summer or were you with us for longer?’

‘That’s right, I temped for a bit after finishing my police training,’ Helgi replied. ‘Then I went on to do a post-grad degree in criminology.’

‘Oh, yes, that was it,’ Reimar said. ‘I seem to remember someone telling me. In the UK, wasn’t it? I’ve often thought about it myself, you know—continuing my education.’

Helgi nodded. He was still standing at his ease in the doorway, as if he were the one in charge. ‘Strictly speaking, I’m still a student. I just need to finish my dissertation, but it made more sense for us to move back to Iceland. My partner got offered a good job, you see.’ Helgi smiled. ‘Nice to run into you again,’ Reimar said. ‘Well, not in the most desirable circumstances, obviously. So you’re having problems with your neighbour, are you?’

‘Yes, you can say that again. The man’s a bloody idiot. It’s only a rented flat, though, so we’ll be moving sooner or later.’

‘He heard a disturbance,’ the younger officer said slowly. ‘That’s right, my partner and I had a bit of a disagreement, but nothing to call the police about. Like I said, youcan hardly turn up the TV without the neighbour appearing on our doorstep. Sound carries terribly easily in these old houses.’

‘Tell me about it,’ Reimar said. ‘I live in a place like that in the west end.’

‘I’m sorry you were put to the trouble of coming out here,’ Helgi went on, adding, after a short pause: ‘Would you like to speak to my partner? To check that everything’s OK? She’s asleep, as a matter of fact, but I can always wake her.’

Reimar smiled. ‘That won’t be necessary.’

His colleague seemed on the point of saying something. Helgi looked at him, and it was as if his silence stifled the young man’s words.

After a moment, Reimar spoke up again. ‘Well, sorry to disturb you, Helgi. I hope we didn’t wake you.’

‘That’s absolutely fine. I was just reading.’

‘Will you be joining us in the police again after you finish your studies?’

‘That’s currently being worked out. I’m in talks with Reykjavík CID about maybe joining them later this year. It would be my dream job, actually.’

‘Great, then hopefully we’ll see you again soon.’ Reimar held out his hand and Helgi shook it before closing the door.

He drew a deep breath. That had gone as well as he could have hoped. He hadn’t expected the prick upstairs to call the police, but he supposed it was understandable, given the amount of noise they’d been making.

He could feel his heart thudding uncomfortably fast but was pleased at how unruffled he had managed to appear in his conversation with the two officers. His police training had come in useful, ironically enough.

It was probably pointless having another go at getting into the detective story he had been reading, but he decided to try. He didn’t want the bloody neighbour to ruin the rest of his evening. Although he was working flat out on his dissertation, he had to take time off sometimes, and there was nowhere he relaxed better than on the sofa with a good whodunnit.

His late father, who had run an antiquarian bookshop up north, had been a keen collector of translated detective novels and had encouraged his son to read them from an early age. After he died, Helgi had inherited his fine old library, and it meant a lot to him. He had read many though not all of the books before and was now working his way through the lot, bit by bit, enjoying the chance to reacquaint himself with stories he had first read in his teens.

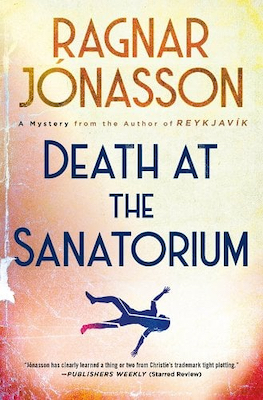

Resuming his seat on the sofa, he opened the book, a worn copy of A Puzzle for Fools by Patrick Quentin. He could remember listening to a play based on the novel, broadcast on Icelandic National Radio when he was a teenager. It had been quite well done, as far as he could recall. The book centred on a series of murders at a hospital—or sanatorium— where the protagonist, Peter Duluth, had been admitted for alcoholism. Quite an unusual topic for a book that had been published in the golden age of the detective novel, on the eve of the Second World War. The story had been on Helgi’s mind recently in connection with his dissertation. Deaths at a sanatorium . . .

He read a few more pages but couldn’t focus. Perhaps the book just wasn’t very good, but he thought it more likely that the police, or rather his upstairs neighbour, had unsettled him. Maybe it would be better to put the book aside for now, to finish at the weekend, and try to get some sleep instead. He would bed down on the sofa, as usual after one of their rows. It was always him who had to make the sacrifice.

He laid the book gently on the coffee table; he always took great care of the collection. They were his treasures, these old detective novels, even though they might not fetch much of a price if sold.

Helgi was eager to get to sleep; as a rule, he had no problems dropping off and he really needed to gather his strength for the job of finishing his dissertation. The subject was so unusual that he had been rather surprised when his tutor in the UK had agreed to it.

A blanket and a cushion would have to take the place of a pillow and duvet tonight, but that didn’t matter; he was used to it and the flat was perfectly warm.

Helgi took off his white shirt and hung it over the back of a chair.

His heart missed a beat.

Just as well his colleagues in the police hadn’t noticed the small red bloodstain on the sleeve.

__________________________________