wi”It’s very satisfying to the human ego to discover the truth; ask Adam Dalgliesh. It’s even more satisfying to human vanity to imagine you can avenge the innocent, restore the past, vindicate the right. But you can’t. The dead stay dead.”

“Life has always been unsatisfactory for most people for most of the time. The world isn’t designed for our satisfaction. That’s no reason for trying to pull it down about our ears.”

“Can we ever break free of the devices and desires of our own hearts?”

–lines from Devices and Desires (1989), by PD James

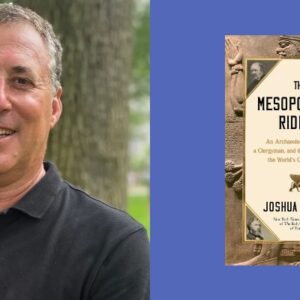

With the Crime Queens of the Golden and Silver Ages of Detective Fiction—Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh, PD James and Ruth Rendell are the most mentioned, although other names pop as well, most commonly Josephine Tey but sometimes Gladys Mitchell or Georgette Heyer or Christianna Brand or Patricia Wentworth, pick your poison—article writers occasionally found the need to ask the question why these “nice British women” felt compelled to write about murder? Perhaps the answer is that they were not so nice! Or maybe nice girls do. Perhaps there were darker undercurrents in the lives of these nice girls which found outlets in the writing of crime fiction.

I’m not sure how “nice” the British crime writing men were either, really, but the question never seemed to get asked why men wrote of bloody murder. Apparently in some quarters it just was not considered ladylike. Some said the same thing about the nineteenth-century sensation novel, though plenty of proper Victorian misses wrote (and read) them.

I do not know how many crime writers of the Golden Age necessarily were “nice,” really. One I feel sure of was pious Freeman Wills Crofts, although even he had an understanding, informed by his devout Christian faith, of the dreadful sin of greed. “For the love of money is the root of all evil,” runs the mantra of many a Freeman Crofts crime novel, “which, while some coveted after, they have erred from the faith, and pierced themselves through with many sorrows.”

The true test of niceness, I suppose, is how it withstands the slings and arrows of those many sorrows. In other words, it is harder to keep the milk of human kindness from curdling when one is miserably unhappy. And certainly the Crime Queens all had travails to deal with in their lives. Agatha Christie might have seemed to have had the perfect Victorian/Edwardian upbringing, but then when the Great War commenced she married an extremely handsome man who a dozen years later with his marital unfaithfulness broke her heart and harmed her mind, leading to her infamous fugue episode, the brief disappearance which in England became a nine days’ wonder (or was it ten).

Some have argued the ingenious mystery writer deliberately staged her own disappearance in a vindictive Gone Girlish act of revenge against her errant spouse. For her part Margery Allingham married a dashingly handsome man, a childhood friend, who turned out to be a compulsive philanderer and is said to have been physically violent with her on occasion. And Dorothy L. Sayers fell desperately in love with free thinking Jewish writer John Cournos, who would not marry her, causing her much anguish. After having had an illegitimate child as a result of a rebound affair with a certain man in the motor trade (really), she ended up wedding yet another man whom she found rather an inadequate substitute for the real thing.

A lot of people were surprised in later years to find that the increasingly girthy and androgynous-looking Sayers had ever married at all. Chatty and not always charmingly indiscreet mystery writer Christianna Brand bluntly pronounced that upon meeting Sayers she had assumed the elder author was, as she indelicately put it, a “butch.” Ashamed of her bourgeois social origins, Ngaio Marsh led a circumspect life of intense privacy (her second biographer speculates that she was a closeted lesbian), as if she was afraid to unbottle strong emotions. Golden Age detective novels, as originally conceived, were well designed for such authors, who wanted to distance themselves from the all-too-real trauma of death and disordered emotions by making light of murder, treating death as a game.

However Sayers, who in 1930 fictionalized some of her romantic travails with Cournos in her detective novel Strong Poison (the one which introduced her alter ego Harriet Vane, who is arrested and put on trial for the murder of her lover), began preaching in the Thirties that death was not just the game she and others had mirthfully played, and that crime fiction should reflect to some degree the emotions of real life. Her detective novels Gaudy Night (1935) and Busman’s Honeymoon (1937) were supposed to reflect this. Both Allingham and Christie also wrote some detective novels that reflected realer, grimmer life more fully. (Marsh not so much in my view.)

So when PD James and Ruth Rendell began publishing putatively “realistic” English detective fiction in the 1960s, it was not as if they were treading entirely new ground. Christie’s non-series detective novel Ordeal by Innocence (1958), actually written right around the same time as James’ debut mystery Cover Her Face, might be a James or Rendell novel, arguably, in terms of its darker subject matter. Allingham’s Hide My Eyes, from the same year, paints a compelling, frightening picture of the deadly consequences of sticking one’s head in the sand rather than facing up to unpleasant truths.

PD James looks out over the sea

PD James looks out over the sea

I believe that the early Crime Queens did, just like the later ones, sometimes draw on darker events in their own lives when writing their crime fiction. Certainly there is no question that PD James did so. Born in 1920, at the very dawn of the Golden Age of detective fiction, James was the product of an unhappy marriage, and her troubled mother was institutionalized when James was but a teenager. Despite being an obviously brilliant person, James had to leave school at age sixteen and take on work. Then she married just five years later, five days past her twenty-first birthday, to a man who would return from the Second World War mentally damaged and himself would be institutionalized, like James’ mother. Before this tragic turn of circumstance, the couple had two daughters together. Her husband would spend the next two decades in and out of institutions, dying by his own hand in 1964.

Having two young children to care for, James entered the civil service bureaucracy after World War Two and achieved considerable distinction in this field. As mentioned she did not start writing her first detective novel until the late 1950s, when she was nearly forty, telling herself that it was now or never. It is no wonder that as a teenager as a form of escape from a uneasy life she was drawn to reading detective fiction, including her idol Dorothy L. Sayers, nor is it a surprise that she was morbidly fascinated with death. Instead of distancing herself from the disturbance of death in her fiction, however, she embraced it. She also put a lot of herself, I am convinced, into her primary series detective, Adam Dalgliesh, as well as other characters.

I have read all but the last couple of PD James mysteries (I started the penultimate one, The Private Patient, twice but have never finished it–not because it was bad, but just because other things came up), and there are definite common qualities to her books, reflective of the author. Let me list some of them:

The primary characters tend to be unhappy high-level bureaucrats or other professionals, reflecting James’ own personal background. They have replaced the landed gentry of the Golden Age. James thought her books much more representative of British society than Golden Age detective novels, but were they, really? Her professionals typically are improbably eloquent, speechifying in long, perfectly composed paragraphs, and quite snobbish and intellectually arrogant. Even with her gentry types and condescension to servants, Agatha Christie still comes off as more of an “everywoman” than James, in terms of her portrayal of characters, especially her village types. Interestingly, James could do “village types” quite well, when she chose to do so. Perhaps she shied away from the Christie comparison.

Religious themes are prominent, especially in the later books. There will be at least one traditionalist Anglican type character, whose faith may be lost or weakening, but who nevertheless stoically Christian soldiers onward through the forms of faith in order to escape from falling into the bottomless pit of abject nihilism. There’s a British stiff upper lipness to it all. I think this was very close to James’ own religious view.

Left Wing radicals are pretty much objectionable nuisances and nutcases who hector inoffensive traditionalists (like James) with their toxic mantras of “political correctness,” today known as “wokeness.” This is in the books from the Eighties onward and it is very similar to the Golden Age stereotype of the Leftists of that day.

Her “better” people are intensely private, despising the conscious airing of emotions and often disdaining even physical contact with others. Certainly Dalgliesh is like this. The stiff upper lip again! I have a lot easier time imagining Lord Peter Wimsey (My Lord!) having sex I do than Adam Dalgliesh.

People’s worth can be identified by the interior decoration of their homes. A worthwhile person will have lots of books and some art, preferably original work by a known artist, in their homes, usually hanging over—to use James’ favorite word—”elegant” (preferably Adam) mantelpieces. They will grind coffee beans to make coffee and never dare be seen with a jar of instant in the house. They will fresh squeeze their orange juice, not pour it out of a carton. Women will frequently bake their own bread. Martha Stewart has nothing on these people. They listen to classical music and hate rock, or pop as they call it. Regrettably, none of these activities will actually make them happy, but still it signifies their worth as human beings.

Middle class people in trade are often looked down upon for their lack of intellectual worth, just like in many Golden Age detective novels, although more humble country people, especially parsons, tend to be admired. Charwomen, aka cleaners, are quirky and colorful comic relief, just like in the Golden Age.

Acne is the stigmata of a weak character. Evidently plucky people do not come out in spots.

Near the end of the novel someone will confront the killer with the truth and the two of them will then sit down for a nice, eloquent philosophical chitchat about the ethics of murder. Earlier in the novel several characters will high-flown rhetoric debate some current issue, like abortion or nuclear power or church reform.

James’ favorite word is “elegant,” while she also loves the words egregious (as in egregiously presumptive), atavistic/atavism, carapace and exophthalmic (i.e., bulging eyes). People in her books “go to bed” with each other or they “make love,” but they never ever “have sex” or, God forbid, “screw” or “fuck.” Fucking is for the coarse and vulgar masses apparently.

Adults drink Ovaltine, cocoa or some milky non-caffeinated drink before going to bed (really going to bed, not having sex). In one book even though it is 1988 a detective inspector still takes these beverage rituals as a given.

James will never split an infinitive to save her life!

Despite James’ insistence that her work was much more “credible” and less snobbish than Golden Age detective fiction, I think that there actually are quite a few similarities between her writing and that of the Golden Age generation, as much of the above wordage indicates. This is one of the things I want to look at in James’ eighth Adam Dalgliesh detective novel, published a little over thirty-five years ago in 1989: Devices and Desires. Coming on the heels of James’ lauded A Taste for Death, Devices and Desires was ecstatically received on both sides of the Atlantic by critics who took their detective fiction very seriously indeed. “P. D. James writes crime stories that deserve the word novels,” pronounced Mark Lawson in the Independent.

PD James and Adam Dalgliesh (actor Roy Marsden)

PD James and Adam Dalgliesh (actor Roy Marsden)

In Devices and Desires Dalgliesh takes leave from Scotland Yard and goes to rural Norfolk to tend to the estate of his recently deceased spinster aunt, Jane Dalgliesh, who appeared earlier as a murder suspect in the third novel in the series, Unnatural Causes (1967). I like this sort of connectivity in mystery series, even if it feels a bit off here, when you think about it.

Jane Dalgliesh lived on the Suffolk coast in Causes, but we are told she moved to Norfolk five years previous to the events in Devices and Desires, after inheriting a converted windmill. We later find that she had a fiancé who died in the Great War, which surely would make Jane in her late eighties when she died. (The novel is explicitly set in 1988.) So when she moved to live alone in a rural Norfolk windmill, she was, what, eighty-three? Hardy lady! Of course the Dalglieshes do so very much value their privacy. James herself lived to the age of ninety-four and remained pretty independent, evidently, to the end. She passed away in her sleep, an easier quietus than her friend Ruth Rendell, a stroke victim, had sadly to bear not long afterward.

Anyway, it just so happens that there is a serial killer, nicknamed The Whistler, who is active in the very same area! The novel opens with the fiend committing his fourth fatal strangling of a woman. This is a very effectively drawn sequence and shows that James could have written an excellent serial killer thriller, had she chosen to do so. But she did not: Rest assured, traditionalists, that this is a traditional detective novel (though see below about the regrettable thriller subplot of another sort).

James limns her setting quite evocatively, I must allow. As usual with James, buildings are important. Here we have an old Victorian rectory (the church is serviced has been pulled down), a ruined Benedictine monastery, Dalgliesh’s windmill (he was sole heir to his aunt’s ample fortune, lucky sod) and, more incongruously, a nuclear power plant. The main characters in the novel are, aside from AD:

1. Terry Rickards, local Detective Inspector, a decent man who respects Adam Dalgliesh but resents how AD dressed him down a dozen years ago when he was in the Yard. Currently Rickards is stressed because his pregnant wife Susie has gone home to be with his meddlesome mother-in-law on account of fear over the depredations of The Whistler.

2. Rickards’ detective sergeant, Stuart Oliphant, who is rather a nasty bully.

3. Alex Mair, head honcho at the nuclear power plant.

4. Alex’s sister, Alice Mair, a noted cookbook author. She and AD, who has recently published a new book of poetry, have the same publisher as James, Faber & Faber!

5. Meg Dennison, a forcibly retired, widowed schoolteacher from London who came to this corner of Norfolk to serve as housekeeper for the elderly Copleys, a retired Anglican minister and his wife.

6. Neil Pascoe, a graduate student on a grant who rather than working on his dissertation or what have you, has formed a local anti-nuclear power group, People Against Nuclear Power, or PANUP, and thrown himself wholesale into leftwing activism.

7. Amy Camm, a mother with an illegitimate baby named Timmy who is living with Neil, though the two are not having, and have never had, sexual relations. What is Amy up to?

8. Ryan Blaney, an artist with four children, the eldest of whom is fifteen-year-old Theresa, whose wife has recently died. Since her mother’s sad demise Theresa, like James after her mother was institutionalized, has been having to take care of her siblings.

9. Hilary Robarts, an official at the nuclear power station and–well, there’s no other way to put it–an absolute stone cold bitch. She’s also Alex’s lover, or mistress as everyone calls her, though Alex has tired of her.

10. Caroline Amphlett, Alex’s beautiful, highly competent and completely impersonal personal assistant.

11. Jonathan Reeves, Caroline’s inadequate, spotty boyfriend, who also works at the power plant.

12. The late Toby Gledhill, a beautiful, brilliant young nuclear scientist at the power station who dramatically and deliberately took a header there to his untimely death. Why?

converted East Anglian windmill

converted East Anglian windmill

So, do you have all that? Of course hateful Hilary is the novel’s main murderee and she spends the novel’s first two hundred pages (!) needlessly provoking a bunch of people to want to kill her, in the manner of her killed-off kind. These are the Blaneys, whom Hilary is threatening to throw out of their cottage, which she owns; Neil Pascoe and Amy Camm, on account of Hilary threatening to sue Neil for libel; Alex, because Hilary is demanding that he marry and give her a child (he made her abort the last one, she claims); Alice, because she is very close to her brother, with whom she lives (he stopped her father from sexually abusing her, for good and all). And there may well be others too. What about Tony Gledhill’s suicide, for example?

As mentioned it takes about two hundred pages actually to get to Hilary’s murder. Many a detective novel would have begun and ended by then, but PD James has lots and lots of backstory to get through. There is also the matter of The Whistler, who kills a fifth woman before finally killing himself, not long before the slaying of Hilary, in the very same manner as The Whistler’s victims.

Yes, it seems that someone with a private agenda killed Hilary and tried to make it look like it was really The Whistler. This limits the list of suspects, seemingly, to people who attended a dinner party at the Mairs where The Whistler’s weird MO was revealed. (He stuffed his victims’ public hair into their mouths and carved an “L” on each woman’s forehead.) These were the Mairs (Alice did the cooking), Meg Dennison and Miles Lessingham, along with Theresa Blaney, who assisted with the cooking. The late Hilary was there as well, along with the great AD himself. AD even discovers the body. Hey, James had to give him something to do in the book, since he is not leading the investigation this time!

So from one perspective all the serial killer stuff is a colossal waste of time—we are even told the killer’s mother was to blame for the murders, which could not possibly get more trite—but on the other hand it is a pretty neat way of limiting the circle of suspects. But does it?

Up till this point I was pretty engaged with the story, which does have beautifully written passages, but then James unleashes this thrillerish whale of a red herring, as it were (concerning the nature of which I will say nothing though I really want to), which to me just felt like a massive waste of time. This takes up much of the novel’s Books V and VI and I would have preferred to have it excised. This sort of action material, more suited to crime thrillers, crops up frequently in James’ later novels. It is like she wrote them with one eye toward their inevitable television adaptations for the Dalgliesh detective series starring Roy Marsden as AD.

Still, there is one of those classic James confrontations between the murderer and the person who knows the truth, as well as a bittersweet ending which lingers in my mind. James may insist that only in the Golden Age mysteries is order restored, but Devices and Desires‘ Finis is pretty optimistic by James’ standards, especially compared with her previous novel, A Taste for Death. The mystery plot of Devices and Desires is far from ingenious, to my mind, but I probably would rate the novel pretty highly were it not for the implausible thrillerish subplot. Also, aspects of the solution are not really fairly clued in my view.

Devices and Desires seems, like many of James’ novels (perhaps all of them), to be about the struggle of rational human beings to get by in a fallen and increasingly faithless world. Intelligent beings may rationalize the outrageous act of murder, but in fact it is really the gravest of sins in James’ eyes and in those of her fictional avatars. There is a deep moral sense to James’ work, a quality she shared with Agatha Christie, although James as far as I am aware never gave Christie credit for this. It lends a measure of gravitas and power to her work.

Even though James’ surrogates, like Dalgliesh, often evince a distaste for humanity on a physical level, they recognize the basic right to life with which each of us is instilled presumably, in James’ eyes, by the Creator. Witnessing the sniveling of Neil Pascoe, AD thinks censoriously “how unattractive it was, the self-absorption of the deeply unhappy.” He reflects how he himself is “good with the words”—he is a published and lauded poet, after all—but “[w]hat he found difficult was what came so spontaneously to the truly generous at heart: the willingness to touch and be touched.” No less an entity than Jesus, we should remember, washed other people’s feet.

But AD values his privacy so highly. Late in her life James discounted the notion that anyone would dare to write a biography of her. (She certainly was not authorizing one.) How egregiously presumptuous an invasion of her privacy that would have been! And more than a decade now after her death no one yet has. Her own autobiographical fragment, Time to be in Earnest, seems to conceal as much as it reveals.

High up in his aunt’s windmill (now his), AD actually incinerates Great War era photos of his aunt and her soldier fiancé, who tragically did not survive the conflict. AD thinks of his gazing at these old mementos of the dead past as “a voyeurism which in [his aunt’s] life would have been repugnant to them both.” For the love of Adam, why?! This does seem to me to represent a hypersensitive desire for privacy. Had I been Dalgliesh I would have saved those photos for posterity. No man is an island. Or even a windmill.

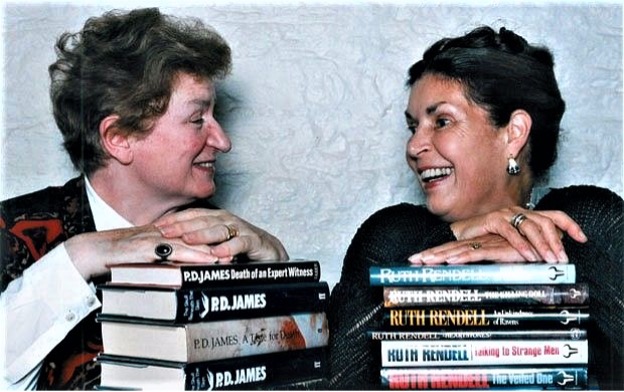

AD, having with Faber & Faber just published a new book of poems, A Case to Answer, to great critical acclaim and sales success (miracle of miracles, he is not just a poet, but a remunerative one!), himself thinks wonderingly how “solitude was essential to him. He couldn’t tolerate twenty-four hours in which the greater part wasn’t spent entirely alone. But some change in himself, the inexorable years, success, the return of his poetry, perhaps the tentative beginnings of love, seemed to be making him sociable.” James herself was achieving great success at this time, of course, and had become fast friends with Ruth Rendell—it was probably one of her greatest friendships in a life that seems to have been for decades singularly devoid of real intimacy.

Gal Pals PD James and Ruth Rendell around the time of the publication of Devices and Desires

Gal Pals PD James and Ruth Rendell around the time of the publication of Devices and Desires

Another James stand-in, the conservative churchgoing widow Meg Dennison, prizes her friendship with Alice Mair and tries to keep to her Christian faith, even though her sufferings have suffused her with doubts. As a teacher in London she lost her post when she outraged racial militants by referring to the “blackboard” as such, rather than calling it a “chalkboard,” and by refusing to take a remedial racial sensitivity course. Did anything like this every really happen? It sounds like something Bill Maher might have complained about on Politically Incorrect. Poor Alice, a victim of PC culture! What would James have said about “wokeness”?

Of her salving friendship with Alice Mair, Meg thinks gratefully of “the comfort of a close, undemanding, asexual companionship with another woman.” After her schoolteacher husband’s tragic death while saving a student from drowning, “she had walked in darkness like an automaton through a deep and narrow canyon of grief in which all her energies, all her physical strength, had been husbanded to get through each day…. Even her Christianity was of little help. She didn’t reject it, but it had become irrelevant, its comfort only a candle which served fitfully to illume the dark.”

It is hard not to see such a character as something of a self-portrait, except that James, rather than modestly retire to housekeep obscurely in Norfolk, remained in London and became one of England’s best-selling novelists. Alice Mair is something of a self-portrait too, I suspect, capturing other aspects of James’ own self. “She’s a successful professional writer,” Dalgleish huffily tells Rickards when he suggests that Alice—a spinster living with her brother who “had no other outlet for her emotions”—might have killed Alex’s mistress Hilary out of overmastering jealousy. “I imagine that success provides its own form of emotional fulfillment, assuming she needs it.”

Indeed! I imagine I would find writing #1 bestselling novels quite fulfilling myself.

When Meg tells of her husband’s death to the unsentimental and atheistic Alice Mair, the latter tartly responds: “It would be perfectly natural to hope that your husband hadn’t died for someone second-rate.” Meg regretfully admits that the boy wasn’t even that, but rather “a bully and rather stupid…. He was spotty, too.” Then she quickly adds: “oh dear, that wasn’t his fault, I don’t why I even mentioned it.” Indeed, Meg: you really should know that spots are not an index of inner worth. As Alice should know that being “second-rate” is not a mortal human failing.

But then throughout the James corpus of crime it seems that acne like stigmata afflicts the weak and (mostly) worthless. Poor pallid, spotty Jonathan Reeves, dominated by his beautiful, confident girlfriend Caroline, comes of banal middle class trade origins: his father is a carpet salesman and naturally the family is Chapel! Jonathan wretchedly thinks to himself: “We can’t be as ordinary, as dull as we seem.” But sadly they are. Hoity-toity Alex Mair sneeringly dismisses Jonathan as “an acned nonentity.” He simply cannot imagine why someone like Caroline would waste her time on him.

People are their environments in James books, seemingly, so that a dully-furnished house signifies dimly-souled people. The Reeves family, Caroline and Hilary herself damningly all live in uninterestingly decorated homes, in contrast with Jane Dalgliesh’s fascinating windmill, where AD has taken up abode for a time. Poor bourgeois DI Rickards, a former Dalgleish acolyte, can’t help enviously contrasting his own banally furnished home (courtesy of Susie, who won school medals for “neatness and needlework”) with that damn windmill: “Dalgliesh’s furniture was old, polished by centuries of use…the paintings were real oils, genuine water-colours….”

High up in his windmill, Dalgliesh, his mind filled with “gentle melancholy,” listens to English composer Edward Elgar’s great mournful cello concerto, thinking how its “plaintive notes” evoke “those long, hot Edwardian summers…the peace, the certainty, the optimism of the England into which his aunt had been born.” This is not at all what I get out of Elgar’s cello concerto (I think of the tragic, atrocious folly and carnage of the First World War which the misplaced confidence engendered by Edwardian pride and pomposity led Europe into); but then I like, and grew up on, Eighties rock music.

Contrarily, when Dalgliesh turns on the tube he is utterly disgusted by a “jerking pop star…wielding his guitar…his parodic gyrations so grotesque that it was difficult to see that even the besotted young could find them erotic.” Take that, you degenerate Morrissey! James was old enough to be my grandmother and obviously did not want her MTV, thank you, which helps explain why her characters under thirty usually are not all that convincing.

When I read James’ crime fiction, I am fascinated by what I see revealed of the author’s own personality, her intrinsic being. I think that her Christian faith blessedly saved her from falling into outer darkness after her myriad personal sufferings, but that, she, like many of us, had a “darker side,” as it were, which she used her writing to explore. No Patricia Highsmith was she, surely, for she was not a sociopathic type like the American crime writer and she did not in the end identify with murderers; but possibly there was some sense of sinister sisterhood under their skins. James understood the fatal temptation to murder. Perhaps this is why her work veers so often toward gloom.

James understood the fatal temptation to murder. Perhaps this is why her work veers so often toward gloom.It is a shame in a way, because there is a lot of evidence that James had a warm and winning aspect to her personality: charm, a sense of humor, kindness, love even. She allows some of this sunlight to filter into Devices and Desires in a long, ingratiating chapter in which Rickards and Sergeant Oliphant interview the middle-class, middle-aged couple who runs the local pub, George and Doris Jago.

The Jagos are refreshingly normal, happy, uncomplicated people—Christiesque village people—and it is ever such a relief to be in their company for a spell and away from all those the haughty, well-educated yet miserable white-collar, Oxbridge professionals. I have no doubt in my mind that PD James could have been a true successor to Agatha Christie, had her life experiences and the era in which she wrote so inclined her in that direction. But James was also responding to the temper of the time; and what many people then wanted were sprawling, nearly 200,000-word mysteries filled with morose murder melodrama.

In the United States Devices and Desires became a #1 bestseller, during one week actually topping books by Dean Koontz, Thomas Pynchon, Jack Higgins, Tom Clancy, Danielle Steel and Gore Vidal. This is all well and good and in its own way a remarkable accomplishment by a proper English Tory utterly out-of-sorts with modernity; but my view of the novel is more in accord with the late Labour politician Gerald Kaufman, who in The Listener wrote rather blisteringly of it: “We have here a brilliant 250-page whodunit. The trouble is what we also have here is a 400-page book. Thirty of these pages are wasted on a silly, melodramatic digression…. Far worse, though, is the mass of irrelevant detail…. James has only to spot for a chance for a digression, and away she goes.” Not to mention Harriet Waugh in the Spectator, who complained that James’ formidable “intellectual energy has been diverted into a fairly pedestrian examination of the moral dilemmas and attitudes of the nuclear industry rather than into the more taxing business of laying a tricky trail and then fooling the reader.”

Hear, hear! To my mind James had done it all much better two decades earlier in her brilliant, economically composed, early detective novel Shroud for a Nightingale, with far more point and something like half the wordage.