The dizzy spells should have been the first warning.

A year after launching my debut novel, I was vaccinated, caffeinated and hard at work on my second book. By age thirty, I’d achieved almost every goal I’d set for myself in my teens: I was self-employed, lived alone, had cash in the bank. Hollywood was (literally) calling. I worked out five days a week. I ate organic. I was doing everything right.

Yet every few weeks I found myself muddled with bouts of dizziness that took minutes, then hours, to clear. More troubling, they were soon joined by bouts of confusion and brain fog that made routine tasks like emptying the dishwasher or folding laundry into endless, labyrinthine time-sinks. Some days I woke up so tired I could barely get out of bed.

But I was too busy to be worried. I wrote six to eight hours a day, seven days a week. I warded off these little hiccups with coffee and tea and caffeine tablets and told myself I would go to a doctor as soon as I finished my second book. I feared that if I didn’t get a move-on, I’d never have the chance to get My Career off the ground. Opportunity withered up fast. Used bookstores are littered with Promising Debut Novelists who never made their mark.

My Career needed me. My Career was everything.

And then one day I was blindsided by a bout of vertigo so severe I nearly fell out of my chair. I told myself I just needed exercise, but a tightness developed in my chest and soon my breathing grew so labored I couldn’t jog a quarter-mile without seeing stars. It was all I could do to drag myself back to my apartment and crawl into bed. I grudgingly gave myself permission to take the day off (but not a minute longer.)

The next day I awoke with a pain in my kidneys that was so severe I was surprised when I didn’t pee blood. My body refused to admit a mouthful of food. When I dragged my manuscript into bed with me—My Career still needed me, after all—I found that my brain fog was so thick I couldn’t recall the way a paragraph had started by the time I reached its end.

I stared at the blinking cursor on my laptop. I’d forgotten how to write a sentence, let alone a book.

***

A week later, in the midst of what I feared was both kidney failure and a nervous breakdown, I was back home on my parent’s couch, racked with shivers and chills and wondering if my health had just ended My Career before it even had the chance to start. I spent the first few days of my convalescence, struggling to read a couple books I’d been asked to blurb but finally gave up: my body and my mind had finally rejected anything at all related to My Career, even forthcoming titles by talented friends. Instead, I puttered around my parent’s apartment, browsing their stuffed bookshelves, digging out volumes on World War II history and English naval warfare and Seventies sci-fi.

Which was when I stumbled over a row of spines that were so familiar from my childhood their colors formed a corner of the wallpaper of my subconscious.

The book’s titles and covers were all more or less interchangeable but their author was legendary. Dick Francis, one of the most successful authors of thrillers in the last fifty years. He was a favorite of my mother’s and I had vague memories of reading one or two of his books when I was younger. I recalled them as clever, nonthreatening, not especially profound (I was a snob in my teens: if something didn’t pull the English language inside out it had clearly failed as a work of art) and a decent way to pass the time. What the hell, I thought, grabbing a few of his books at random. Reading these beats staring at the walls.

A few minutes later, I found myself not only reading Francis’ books, but falling into them, losing myself in their stories with a pleasure I hadn’t experienced since I’d quit my day job and pivoted my entire life to satisfy My Career. Over the coming months—through six weeks of antibiotics, two ER visits, and the long, long waning malaise as my body struggled to rebuild itself—I was kept company by a former racehorse jockey so British he could shame the Queen.

Even at the time, I wondered why.

Like most bestselling authors, Francis’ reputation has waned precipitously since his death in 2008. I have it on good authority that it was once impossible to sit on an airplane (wreathed, presumably, in cigarette smoke) without seeing one of his thrillers in someone’s hands. A decade before he died, Francis estimated that he’d sold more than six-hundred million books worldwide. To his credit, a good many of his thirty-eight novels remain in print.

But why are they so popular? And more personally, how did they get me through the most grueling period of my adult life?

As any decent suspense novelist will tell you, the answer probably lies in the past.

***

Dick was born Richard Stanley Francis in 1920. He was raised around horses. Soon, he dedicated his life to racing them. He enjoyed a successful career as a steeplechase jockey (which is to say, a hurdle racer) that ended when he was thirty-six and his mount, Devon Loch, the Queen Mother’s horse, collapsed forty yards from winning the Grand National. To this day, the horse’s collapse is one of the legends of the British racing world. No one knows why its back legs simply gave out a few moments after it had pulled ahead of the competition. A lazy critic would be tempted to wonder if Francis spent the rest of his life inventing fictional explanations for this permanent enigma.

A year after the Devon Loch disaster, a bad fall finally convinced Francis to quit while he was ahead. He worked at a newspaper for a time, writing racing articles and even a successful memoir, but when the Sixties rolled around “the threadbare state of [his] carpet and a rattle in [his] car” sent him looking for a third, more lucrative career.

Long a fan of crime novels—they helped him pass the time on the long train rides between races in his jockeying days—Francis published Dead Cert in 1962, a book that more or less encapsulated everything his readers could expect of him for the next thirty-eight years. It stars an amateur jockey, Alan York, whose friend, another jockey, is killed when his horse suffers a mysterious fall during a race (sound familiar?). Alan proves himself to be an inherently decent, savvy man who refuses to stop digging into the supposed accident even when a similar attempt is made on his own life. A gambling racket is unmasked. A daring escape is made, cross-country and on horseback, before justice can be done.

In book after book, Francis would revisit these same themes endlessly: brave young men thrust into dangerous mysteries that always involve some aspect of the racing industry. The horse world is, in fact, an inspired setting for skullduggery. At every race course there are the old money aristocrats who own most of the horses, the new money swells with dubious pasts trying to buy their way into society, the working class men in the stables and, winding through it all, a league of battered jockeys and a few million pounds of seedy gambling money.

But Francis had more than just racing on his mind. In almost every one of his future books, his reader is taken on tours of industries and hobbies (mostly) unrelated to the ponies. Sometimes it’s airplanes (Flying Finish), sometimes it’s wine and spirits (Proof), sometimes it’s trains (The Edge.) In Come to Grief, we’re sent on crash courses of the tabloid industry, high-end TV advertisement production companies, agricultural grain processing, children’s leukemia, custom fabric weaving (really) and—in stomach-churning detail—the most efficient way to lop off a live horse’s hoof. The amount of research that went into each book is impressive. The fact that Francis wrote a book a year in which all of that research is built perfectly into a suspenseful plot is nothing short of awe-inspiring.

This is where we talk about the fact he had more than a little help from his wife, Mary. Francis was always up-front about the immense role she played in researching, brainstorming and editing his books, but there have been allegations through the years that the collaboration was perhaps more lopsided, with Mr. Francis serving as nothing but a figurehead for his wife’s novels. We’ll never know for certain, but Francis’ own explanation seems just as likely: “I am Richard, Mary is Mary and Dick Francis was the two of us together.”

When Mary died, literally, in Richard’s arms in 2000, he more or less retired from the game. A few years later he published the final novel under his own name and collaborated with his son, Felix, on a few more, but the later books lack the panache of the earlier fare. The last book Richard and Mary wrote was entitled Shattered. Fitting, really.

***

Between Dead Cert and Shattered there stretches a succession of stone cold hits of such consistent quality you’re almost—almost—tempted to think they might have been easy to write. Of these hits, there are a few standouts. Whip Hand and Come to Grief (both of which won the Edgar, along with Forfeit) deftly juggle something like three major plots and a half-dozen subplots, all in a little over three-hundred pages apiece. Trial Run, Francis’ brilliant take on the espionage novel, accomplishes the neat trick of taking four hard turns in its plot without ever becoming too clever by half. Proof has one of the most satisfying final pages of any novel I’ve read in any genre.

But it’s his novel from 1989, Straight, that swallowed me up when I was too sick to think about anything else. Its hero, Derek Franklin, begins the novel marooned on a couch (sound familiar?) laid up after a racing accident that might signal the end of his jockeying career (“If you’ve never felt your ankle explode, don’t try it.”) His phone rings, and Derek learns that his much-older brother, Greville, has been mortally injured in an accident of his own. A mound of fallen building scaffolding will do that to you.

Greville ran a tidy business wholesaling gemstones, a business he has now left to our hero. No one is as shocked by this as Derek, who knows nothing about running a company and even less about rocks. The problems soon mount. Someone has burgled the office. Greville has secretly borrowed one-and-a-half million dollars to purchase a fistful of raw diamonds that no one, now, seems able to locate. Over at the racetrack, there’s dirty business afoot with Greville’s horses. Derek (and the book’s villains) keep finding creative ways to re-shatter his mending ankle. And drifting through it all is a beautiful, wealthy, very married woman with a few secrets of her own.

Francis employs a couple tricks in each of his books to get his readers hooked, one of which is a dynamite first paragraph. Straight’s might be the best of the best: “I inherited my brother’s life. Inherited his desk, his gadgets, his enemies, his horses and his mistress. I inherited my brother’s life, and it nearly killed me.”

This is excellent, but Straight has more treats in store. Even by the standards of Francis’ goodhearted heroes, Derek is especially likable. He and Greville were separated in age by almost twenty years. “By the time I was six, he was married, by the time I was ten, he’d divorced. For years he was a semi-stranger whom I met briefly at family gatherings, celebrations which grew less and less frequent as our parents aged and died.” (Note, here, another of Francis’ secret weapons: a style that Philip Larkin called “laconically gripping.” It uses a careful, compounding rhythm and a precise array of ironies to keep us satisfied and curious about every new dollop of information while never allowing itself to be rushed.)

Although Derek and Greville reconnected as adults, Derek spends the majority of Straight recognizing how little he actually knew his brother. Somehow, with a bonanza of mysteries unfolding, Francis still finds time to fill the book with subtle, trenchant moments of nostalgia. “I borrowed one of [Greville’s] shirts and a navy silk tie and shaved with his electric razor…and brushed my hair with his brushes.” These objects bring him closer to the man he’s lost, but in the end, “I put on my own suit, because his anyway were too long.” Like the missing diamonds that haunt Derek for much of the book, Greville was both impossibly valuable and irreplaceable. That suit will never be worn again.

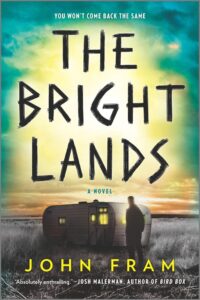

I realized, in reading Straight, that I was actually re-reading it. Years back, at some point in my teens, I’d plucked it off my mother’s bookshelf (had I been ill then too? I wouldn’t be surprised) and in the weird subconscious alchemy we optimistically call “the writing process,” it exerted a powerful influence, years later, on my first novel, The Bright Lands. In that book, a man must investigate the life of a much-younger brother he never really understood. The parallels run deeper. At one point in Straight, as Derek combs through Greville’s calendar, he discovers that his brother never missed the chance to watch each and every one of his, Derek’s, races. “‘Derek won!'” is written next to the jockey’s proudest achievement. Derek, like the hero of my own novel, realizes that through all the years he spent never thinking about his brother, his brother was thinking about him.

It was profound to reread Straight almost twenty years later. I might have barely remembered the book, but it had clearly made a powerful impression on me in the days when I was laying out all those bold plans for My Career. Back then, it hadn’t struck me as crazy to devote my entire life—and livelihood—to writing novels. Success was surely the inevitable result of diligent hard work. The thought I might one day require months without work would have been so terrifying I’d have had to laugh.

“Decisions are easier to make when you’re young,” Derek muses near the end of Straight, when he’s faced with a painful moral quandary that seems fated to hurt him and everyone he knows. When he was younger, he would have known exactly what to do. Now, in the wake of his life’s first true, painful derailment, he is all too aware that pain and failure are not only potential hazards, but likely ones.

Sometimes, with no warning, life just runs you over at a gallop.

***

I picked up another Francis novel the same night I finished Straight, followed by another and another and another. Whenever I had the energy to care about much of anything, I wondered what about these books kept calling to me. After all, Francis isn’t without his faults: his prose can drown in adverbs when he’s not careful, and a subtle snobbishness ensures that his upper-class characters are seldom evil and his new-money hustlers, with their cologne and loud ties, are behind most of the problems of the modern world.

But now that the dust is settling and my life is resuming, it’s easy to connect a few dots. Why did I keep reading Francis’ novels? It’s simple. They were never about inventing fictional explanations for Devon Loch’s mysterious collapse. They’re about solving the harder problem: how does a person keep going after everything falls apart? In Proof, our protagonist Tony Beach begins the novel almost paralyzed with grief by the death of his young wife. Sid Halley, hero of Odds Against, Whip Hand, Come to Grief and Under Orders, still dreams of the races he used to win before a horse’s hoof destroyed his left hand. In Straight, Derek doubts he’ll ever have half of his bother’s decency and intelligence.

But in every novel, these men find the courage to keep going. They do the right thing. They survive.

What kind of stories could be better for a fit, ambitious young man who was doing everything right and still got knocked off his horse? When your stuffed bank account starts running thin after batteries of tests and doctor’s visits and the means of replenishing the pot are beyond you and all your adolescent plans are dragged to a bone-shaking stop—is there anything more comforting than seeing evidence that a jockey at the top of his career lost everything and yet still found a way to survive, year in and year out, with stories that have outlived him? For weeks and weeks I spent in bed, the last line of Straight was like a promise from the future:

“I’d inherited [my brother’s] life and laid him to rest. And at that moment, though I might hurt and I might throb, I didn’t think I’d ever been happier.”

***

In the end, I was on antibiotics for six weeks to fight what appeared to be a mysterious and stubborn kidney infection but the exact cause of my collapse was never pinned down. In the end the likely culprits were overexertion, over-stress, over-caffeination. Coming off of all those antibiotics and all that coffee was almost as hellish as the illness itself. If you’ve never had a migraine and diarrhea for five days straight, don’t try it.

In all, I was in bed for a little over two months. For most of that time, I doubted I would ever be able to write again. Between the antibiotics and the coffee withdrawals and the compounding anxiety, I couldn’t even remember what it felt like to exist in the state of mind good writing depends on. It’s an intense state of concentration coupled with a sort of ebullient, freewheeling ease, not unlike Francis’ many descriptions of how it feels to race a horse.

For the first time in my life, I had run out of ideas: for stories, for the future, for myself.

There’s a scene in Whip Hand where Sid Halley is invited to ride a horse that looks ready to sweep the racing world. Sid is understandably nervous. With his prosthetic hand, “It would be easy…to upset the lie of the bit and the whole balance of the horse…I could lose him the Dante and Derby and any other race you cared to mention.” Climbing aboard, Sid prays, “Let me not make a mess of it. Let me just be able to do what I’d done thousands of times in the past; let the old skill be there.”

Yesterday, as the deadline for this article loomed and not one word of it was written, I approached my desk like I was afraid it would kick me. I sat down. I picked up a fresh pen. And like Sid on his horse, “It suddenly came right, as natural as if there had been no interval.”

___________________________________

Read John Fram on Barbara Vine and growing up queer in Texas.

Read Neil Nyren on Dick Francis: A Crime Reader’s Guide to the Classics.

___________________________________