I try to be good but fail every day.

My natural state is lazy, self-indulgent, resentful, and dangerously avoidant. The damage I’ve done in life has mainly come from not-getting-around-to something I ought to do. If you’re still waiting for my thank you card or RSVP or post-retirement letter of recommendation or final portfolio grade, you may already realize this. (I’ve chosen not to list some of the most dangerous consequences of my flaws. See? Avoidant.) I’ve got a history of aiming to repress these petty, slothful habits. But I get tired. Sometimes I long to relax into my own worst self with a bowl of ice cream for company and see what happens if I just stop trying. It’s part of what makes me hard sometimes to work with. I’m at heart a malingerer. Yet I’ll resent you for criticizing me about this, because, secretly, I’m also ambitious. My type is difficult.

Maybe that’s why I grew up loving the difficult girls of fiction who just let their uniquely naughty flags fly. Louisa May Alcott’s Jo March burning her sister Meg’s hair in Little Women, Harper Lee’s Scout fighting poor Walter Cunningham in To Kill a Mockingbird, or Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby selfishly biting once into every single apple in Ramona the Pest.

The difficult girls made great protagonists. Their character flaws provoked events. I liked the trouble they caused, especially because they almost always got away with it anyway, without permanent consequence. In schoolgirl fiction, difficult meant challenging, spirited, tomboyish, funny. I expected these qualities to blossom into adult awesomeness. I wanted to be one of the difficult girls.

Then I grew up and the difficult girl characters did too, becoming for me the more troublesome, difficult women of historical crime fiction, which I devour now the way I did those schoolgirl stories. But in adult fiction, when we talk about women, difficult mainly means unlikeable.

So what makes a woman unlikeable?

It’s easiest to like difficult woman characters when their difficulty is a direct result of crimes or other tragedies they’ve survived. They’ve earned their difficulty, like Charles Portis’s Mattie Ross in True Grit. Or when they’re difficult in defense of children.

But what kind of woman is unlikeably difficult?

A selfish, ambitious woman.

We’re mostly in the habit of accepting selfishly ambitious men characters. Just check the best-television-ever lists: Breaking Bad’s Walter White, Mad Men’s Don Draper, The Sopranos’s Tony Soprano, Game of Thrones’s Tyrion Lannister, House of Cards’s Frank Underwood, Peaky Blinders’s Tommy Shelby, Succession’s Logan Roy, or Ozark’s Marty Byrde. I could go on but you get it. Their selfish ambition tends to make them charismatic.

We’re less ready to like the selfishly ambitious women, like Ozark’s Wendy Byrde or Killing Eve’s Villanelle, though we find them all over Netflix and Prime Video. Their ambition almost unsexes them, renders them not recognizably or acceptably female. Can we really even trust Wendy Byrde with her own children, whom she loves, when we learn about her boundless ambition?

Readers tend to push back against the distasteful behavior of such women, even if we know they need to act that way to achieve what they do. Maybe we don’t really want them to have big worldly goals.

I think it gets especially interesting to read the difficult, ambitious ladies of historical crime fiction because their me-me-me drive is thrown into high relief against the female ideals of historical cultures. Today’s tee shirts and mousepads say, “Well-behaved women seldom make history.” They didn’t say that back in the day.

Whether or not I like them, some difficult women of historical crime fiction have nestled into my consciousness. They’re memorable. They suggest something I simultaneously want to reject and honor in myself. Here’s a handful in case you’d like to see what I mean.

Sarah Howard, in Caleb Carr’s The Alienist

(Published in 1994, set in 1896.) Sarah works as a secretary for police commissioner Theodore Roosevelt but also becomes a valuable member of Dr. Laszlo Kreizler’s team as they try to catch a serial killer. She’s undeniably ambitious. Sarah’s decision to work in a male-dominated environment like the police department in 1896 shows her drive to break social norms. The traditional female roles just aren’t enough for her and she seeks opportunities to prove herself. She does good, against a bad man. She’s on the likable side of the spectrum.

Odalie Lazare and Rose Baker, in Suzanne Rindell’s The Other Typist

(Published in 2014, set in 1920s.) Rose is a NYPD typist when a new girl, Odalie, joins the precinct. Rose becomes infatuated with her, leading to a twisted friendship and a series of dark events. Rose isn’t overtly ambitious. She desires stability and seems to adhere to a strict moral code. But as the story unfolds, her infatuation with Odalie causes her to act outside her usual boundaries. Her unreliability as a narrator makes it hard for the reader to understand her. She doesn’t sit easy in the consciousness. Odalie is more explicitly ambitious, her past and motivations unclear for most of the novel. She wants a more luxurious life and is willing to manipulate situations and people to gain that.

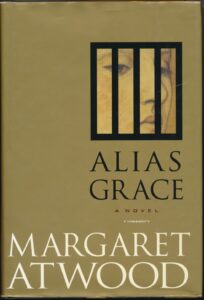

Grace Marks, in Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace

(Published in 1996, set in 1843.) Based on a true story, Grace is a domestic servant and convicted murderer. A young doctor researches her case, trying to figure out whether she’s innocent or guilty. Grace’s life revolves around survival, not conventional goals of power or status. But, again, she’s an unreliable narrator, making the reader second-guess the truth of her motivations and their own empathy.

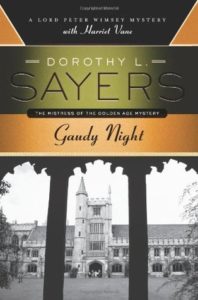

Harriet Vane, in Dorothy Sayers’s Gaudy Night

(Published and set in 1935.) One of Sayers’s most iconic characters, Harriet’s undeniably ambitious, a successful mystery novelist who also attends university at a time when it was uncommon for women to do so. Some readers find Harriet selfish, due to the way she treats beloved Lord Peter Wimsey. She won’t commit to him, despite his obvious love for her. She wants to maintain her independence and not be an appendage to any man, no matter how much she cares for him. She challenges social norms. Her independence and insistence on to making choices on her own terms sometimes seem selfishly contrary to readers loyal to the good Lord Wimsey.

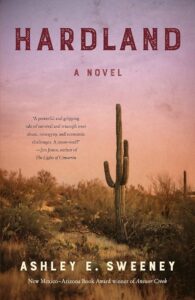

Ruby Fortune in Ashley E. Sweeney’s Hardland

(Published in 2022, set in 1899.) Set in the Arizona Territory, Ruby must either murder her abusive husband or live with bruises that never heal. One bullet decides it. Once the “Girl Wonder” of the Wild West circuit, Ruby becomes a single mother of four boys in her hometown of Jericho, an end-of-the-world mining town. Ruby runs a roadside inn, hosting drifters, grifters, con men, and prostitutes—people she innately understands. She has a love affair that puts her life and livelihood at risk, but she won’t let him go. She does what she figures she needs to, in order to provide for herself and her sons. Ruby’s strong, sexual, skilled with a gun, and unequivocal about her own survival and that of her children, which, for many readers, rescues her from unlikability, since mother-love is a saving grace, maybe the saving grace.

***