I don’t even remember how I came across Vine Street, British author Dominic Nolan’s third crime novel, because it is published in the UK and not readily available in the U.S., but by the time I finished the first chapter, I was hooked. This was a major talent with an original voice. The story, which jumps between the 1930s, the 1960s, and the early Aughts–spending most of the time in the ‘30s in London’s seedy Soho neighborhood between the wars—follows Leon Geats, a vice cop who likes the criminals he’s supposed to police far more than he does most of the coppers he works with.

Despite the gruesome murders—based on the real-life murders of foreign sex workers during the period—Geats’ passion wears off on the reader and you find yourself wanting to inhabit this shady world and the big and burly and broken hearts that love it. And without giving anything away, I’ll say that the twist at the end is perhaps the best sleight of hand I’ve read in any book. Just masterful plotting.

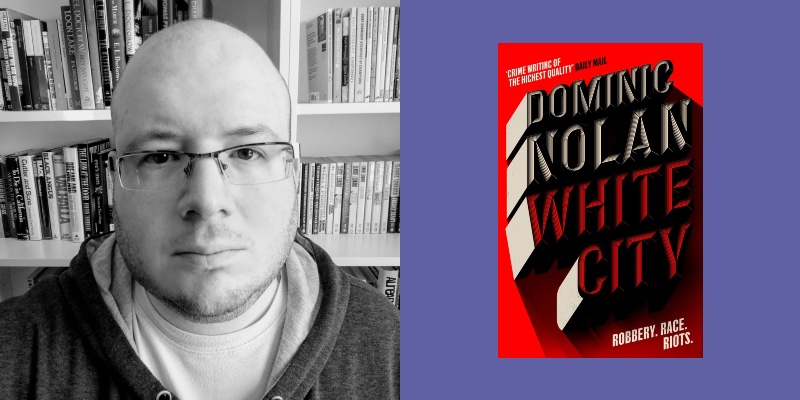

So when I saw that Nolan had a new historically-based crime novel coming out in England in November, I couldn’t wait to read it and I got in touch with Nolan to arrange for a copy. It was again peopled with deeply conflicted, powerfully drawn, tough and tragic characters racing around real historical events and bumping into real people. Think of a British James Ellroy without the ego or the noxious right-wing delight in racist epithets.

But, as one might guess, race is central to White City, which follows several different characters in the long aftermath of a 1952 heist and ends amidst the racist street riots in 1958. So it was shocking when, almost immediately after I finished the book, I saw scenes that could have been lifted from the book playing out in the present—not in London but in various other English cities.

I knew I had to talk to Nolan about what was happening. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity. And, for god’s sake, publishers: Put this guy on your roster and get these books out in America. Vine Street is already a classic and White City will soon be.

Baynard Woods

Both books are historical crime novels set in different periods. Vine Street from 1935 to 2002 and White City from 1952 and moving onward from there. Tell me a little bit about what you’re trying to do with writing historical crime fiction.

Dominic Nolan

I’m always interested in looking backwards. I think you get a more political perspective of what you’re writing about. You’re removed from the immediate context. I think anytime you write period, it becomes political. And I’m usually interested in writing about working class issues, working poor, working criminal, those kinds of areas.

I like filling in the gaps of history. More than 99% of people who existed in the past are lost to history, so I’m interested in joining the dots between the stuff we know, the established historical record, and digging a little bit further into what it was in the streets and what people at that level were doing.

With Vine Street, I was really interested in the way jazz had come into the nocturnal spaces in Britain and changed them, made them more contemporary. London’s always been a city of villages, and a lot of those villages are villages of migrants. So, there’s Soho, which was originally built, like a lot of areas in London, with the intention, the ambition, of it being housing for kind of upper middle class, the new mercantile classes of the Industrial Revolution, which never happened. Those kinds of people never settled there, and almost immediately it became a very French area. There were a lot of Huguenots. It was known as Little Paris originally. Then, you’ve got a very big Italian community. Then a Greek community and an increasingly intra-London migration of the Jewish community from the East End to Soho. Although they lived next to each other in a relatively small space, the nightlife wasn’t very integrated. So you had Italian clubs or restaurants, you had Greek clubs and restaurants, but the groups never really mingled until jazz came. So this was the scene in the ‘30s. These clubs started drawing together much richer crowds, and people were going to them because they weren’t really connected to any one community, because of the West Indian connection. So for the first time, all these little groups of migrants started coming together.

Baynard Woods

Part of what is so great about the book, and so charming, is the depiction of Soho and the underworld and the nightlife, but you also came up with this half-cop/ half criminal character, Geats, to walk us through this world.

Dominic Nolan

Characters are the main thing for me. I have to plan the novels, because an amount of research needs to be done, you know, into the time and the place. But I don’t tend to plan plots that much. I like the story to come from the characters, so I’ll plan incidents, stuff that actually happened in history that I’m going to build the novel around. A lot of the early work I do in any novel is character and tone. And the tone is all about how I’m drawing the place for that vibe.

Baynard Woods

I don’t usually fall for a police officer as a hero in a book, but…

Dominic Nolan

I guess I’m with you. Crime fiction can be particularly guilty of lionizing law enforcement even in the face of stuff happening in the real world. We see in our news time and time again that there’s almost endemic corruption in any major law enforcement department or organization. But Geats is an unusual character. There’s an early scene where he think he can just blend into the background in clubs, but he obviously can’t— everybody there knows who he is and what he is, and the fact that he’s this loner speaks volumes about him, even though he thinks he’s incognito.

Baynard Woods

In White City, to push it even further, one of the main characters, Dave Lander, is a cop, and part of a family of cops, but he is so far undercover he is also actually working as the enforcer for a criminal crew.

Dominic Nolan

White City was different. There was a cop in Vine Street called Lander who was based on a real person. The Lander in White City is entirely fictional but I knew I had this character whose uncle died and had been made to look like a hero but he had to live up to this legacy in his family that wasn’t true but overshadowed everything. That was where I started, before I realized that what I wanted was to follow the kind of character you don’t always see in the crime novels, the characters who get left off, gets left behind when the crimes happen, the wives, the children. How do those families exist when the men have either gone to prison or are dead? What happens to them?

I started thinking about how that would work and how cities exist as an organism almost. Everything’s a network. Everything’s connected, even if it’s several steps removed. So you might not ever realize how you’re connected to things. So the two families in the novel are intimately connected by this crime at the beginning, but really, they never meet in any substantial way other than at the end, in a moment of violence where two of them come together. But even then, they don’t know that they’ve already been connected almost a decade earlier, because there are these networks of crime and of poverty, and these things are inextricably linked to social problems like housing, like gentrification, like corruption of councils and police. So I wanted to get under that corruption to see how it actually festered, how society operated under it. And I had a pretty good idea that I wanted to end with the riots. Because in many ways, that explosion of violence, almost atavistic violence, was the inevitable ending to a lot of social problems. And we see it time and time again, particularly in London. I mean riots almost exist in cycles in London, they’re coming off issues of poverty, relating to jobs and housing and how usually there’s a white riot that’s directed at immigrants when it’s like, why are you angry at them? They’re not the ones that have ruined housing stock. They’re not the ones that have driven inflation up and driven rents up. You know, it’s crazy.

When I was reading about that period, there were so many parallels with today, which became even more apropos, I think, more recently, the riots that have broken out across the United Kingdom, in a very similar situation. So in 1958 you also had multiple riots, not just in Notting Hill, but in Nottingham in the weeks leading up to that, and really all summer across that area of London.

Baynard Woods

So for a couple years, you’d been living in this historical, fictional world, writing the book and then you’re in that weird, awkward period of waiting for your book to come out after it’s done, and then history rhymes again with the world that you’d been writing. And really similar things were playing out on the streets with the racist riots in England this summer. That must have been surreal.

Dominic Nolan

The minute I started really researching into the’ 50s, it was obvious that there were parallels to today. The right wing politician that existed then exists now. The same social problems existed, gentrification, housing; I just didn’t expect it to literally explode. Even if the causes are a little different. In the ‘50s, we were coming off the back of the war, so the country wasn’t rich, the city had been damaged and they’re looking for any kind of hope. And they said they see everything they promised after the war going somewhere else. It was like somebody jumped over them with the promise of the future. And it’s a question of who do you blame for that? And nobody ever really seems to blame the people responsible. They seem to blame new faces that they see, because at the same time, there was an influx of West Indian immigration.

Now, while we haven’t had a war, we’ve had 15 years almost of conservative austerity, which has caused major economic malaise, certainly in the cities of the North. The interesting thing this time was there was very little trouble in London. It was the northern cities across Lancashire and South Yorkshire, and in some other cities down south Plymouth, which is crazy. It’s one of the wealthiest cities in the country.

You hear [from conservatives] about how London is proof that multiculturalism doesn’t work, but for someone who’s lived there their whole life, for me, it is proof that it can work. London is a pretty integrated city. London is one of few major cities in the world where it does work on a regular basis. So, it’s telling that when these problems started, they didn’t really kick off in any substantial way in the capital. It was in smaller cities and cities where ethnic communities are more stuck in one place, as opposed to all over the city. That may be a signpost for how we fix these things. I just think cities that adapt blend themselves better. The right wing will criticize London and say, it’s not the capital of England anymore. It’s the city of the world. Is that not what we want? This isn’t the new thing. People always wanted to come to London because we went to them in the first place. And, I think London’s the way forward in that regard. In fact, the biggest crowds in London showed up to peacefully protest against the riots, supporting the other side, saying that we should all be living together side by side. As I said, that’s what I was interested in in Vine Street, where you get these migrant communities juggling together.

–White City will be released in the U.K. on November 7, by Headline Books.