For more than three decades, Don Winslow has written bestselling novels about everything from the War on Drugs (with his sweeping Border trilogy) to police corruption (“The Force”) to mafia hitmen (“The Winter of Frankie Machine”). Yet even as he produced these books at an astounding rate, his muse kept directing him back to a sweeping epic set among the gangs of New England in the 1980s and 90s.

That epic eventually manifested as a trilogy, concluding with the imminent release of “City in Ruins.” When this latest book begins, protagonist Danny Ryan has become a major power player in Las Vegas. He’s a long way from the Rhode Island gang war that powered “City on Fire,” the first book, as well as the Hollywood backstabbing and catastrophe that marked “City of Dreams,” the second. But like the heroes of all epic tragedies going back to the Greeks, hard-working, fast-moving Danny can’t achieve the velocity necessary to escape his past—an intense rivalry with another mogul on the Strip devolves into death and destruction, threatening everything he holds dear.

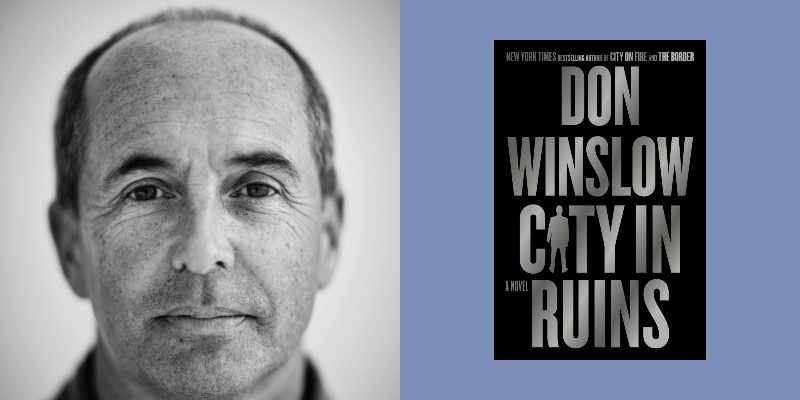

If you’ve followed Winslow’s career, you know that “City in Ruins” is his last book before retirement. For fans, that makes its imminent release bittersweet. To mark the occasion, Winslow chatted about the trilogy, his career… and whether there’s any chance he’ll reverse that decision to retire.

The Danny Ryan trilogy is set in the 1980s and 90s, and bounces between Rhode Island, Hollywood, and Las Vegas. What made you decide on that particular time period as opposed to modern day, or even the 1950s and 60s?

Several reasons.

The 50s and 60s have been done, and done so well, in iconic works such as, obviously, “The Godfather.” There was no point in my retreading that ground.

Second, I wanted the trilogy to end in Las Vegas in the 90s because I wanted to come in after the major power of the mob was over. The 50s and 60s in Las Vegas were obviously fascinating, and rich ground for a writer, they’ve also been done. I wasn’t that interested in covering the era of the Rat Pack, or even of Lefty Rosenthal and Tony Spilotro. I am very interested in transitional eras, such as Las Vegas in the years when corporate money was taking over but when there was still a residual mob influence. That seemed the most interesting time to bring Danny in.

Third, I wanted direct access to the years I was writing about through the whole trilogy. That is, I wanted a time within my own memories and experiences. I knew Rhode Island, Hollywood and Las Vegas in those years. They were evocative for me in a way that made them… not easy, but powerful… to write. Also, that period allowed me to talk to people who were there, which was invaluable.

You’ve been writing this trilogy, on and off, for three decades. When you started out, did you have a detailed idea of the plot and character arcs, or were those things that developed gradually as you worked over the years? In the end, did the final versions of the books differ radically from your initial vision?

Well, in a project that took almost thirty years from conception to completion, things are going to change. Having said that, the overall concept—to create an epic that would be a standalone, modern crime saga while also a retelling of Greek and Roman classics—never changed. What developed gradually were the specifics. While I always knew, for instance, that Danny Ryan would stand in for Aeneas, and that the general arc of his story would track the “Aeneid,” the details of how to make ancient events truly modern were challenging, and the solutions did change over the years as I got better ideas. It took a whole lot of bad ideas to get to the good ones, and I’ll bet I hit ‘delete’ on literally hundreds of pages. Some of the developments were surprising—for instance, I didn’t expect Danny’s mother, Madeleine, to become such a major character, but in researching and writing her I became fascinated. It happens that way sometimes.

I knew that Danny would have to build an empire, but it was a big question as to what that could be in the 1990s. A drug empire was too easy a solution—there had to be something better. I finally hit on Las Vegas and the gambling industry. I’m a little embarrassed that it took me years to hit on that. But once I did, the third book, “City in Ruins,” became possible. And once I hit on the idea that the central conflict would be over a valuable piece of real estate (not a woman, as in the “Aeneid”), the book really took off.

The trilogy is also an extended riff on classical literature. The first book, “City on Fire,” recalls “The Iliad”; the second, “City of Dreams,” echoes a big chunk of “The Aeneid.” With “City in Ruins,” where do we stand in terms of the parallels to epic poetry? (While I was reading the end of your trilogy, I was also listening to the audiobook version of Emily Wilson’s translation of “The Iliad,” and I was really struck by how certain themes—honor, vengeance, carrying your people through hardship—have endured over the centuries.)

“City In Ruins”—which, as in the whole trilogy, can be read with no reference to the classics at all—tracks the last third of the “Aeneid,” the last books of the “Odyssey” and the final play of the “Orestes” trilogy by Aeschylus. My goal was to create an entire world, peopled by modern, approachable characters, from those epics. Initially, I intended to do only the “Aeneid” and Danny, but, again, I found some of the ‘secondary’ characters so interesting that I wanted to tell their whole stories.

Picking up on your comment on enduring themes, that was the impetus for the whole trilogy. When I started to read the classics, I was struck at [how] their themes still remained relevant in not only contemporary crime fiction, but also in real-life crime history. I already knew the Helen of Troy story from things that were happening around me when I was growing up. I felt that I already knew these characters, these people.

When we consider the origins of modern crime fiction, we always—as we should—look to Chandler, Hammett, Christie, Doyle, et al., but I think that we look for our roots in too shallow a soil. We should also look at Dickens, Shakespeare, Cervantes, and yes, Homer, Virgil and Aeschylus, because, as you mentioned, those themes of honor, vengeance, loyalty, revenge, power, lust and love have never changed. If you shot some of their stories in black and white and put a trumpet score behind it, you’d have a noir film.

Much of “City in Ruins” takes place in Las Vegas, which is the setting of many a gangster epic (as well as an incalculable amount of real-life gangster drama). Knowing that, how did you approach Danny’s story in Vegas so that it stands out from all the gangster/business intrigue stories that have come before?

Mostly by setting it in a specific era, that is, when corporate money had taken over from organized crime. I thought there was a seam in there that I could mine without being in the shadow or stepping on the toes of such great works as “Casino.” I know my Las Vegas crime history pretty well—I wrote about it at length in a book called “The Winter of Frankie Machine,” and I didn’t want to repeat that.

I think that empires are at their most interesting at two points—when they’re on their way up and when they’re on their way down, and this period gave me the chance to write about both. I also liked the societal commentary that it provided. To paraphrase Shaw, “Any vice that society can’t control it turns into a virtue,” and that is certainly the case of Las Vegas and the gaming industry as a whole. ‘The numbers’ used to be a crime, now buying a state-run lottery ticket is a civic-minded act. Las Vegas has come to pride itself on being squeaky clean as regards its gambling operation, but it can no more escape its past than can Danny Ryan. There will always be that taint, that, let’s be honest, seductive scent of criminality about it that they even use in their marketing—“What happens in Vegas… .” So I was interested in that transition, how a guy like Danny could navigate both the city’s and his own attempted changes. I think that’s what sets the book apart.

I know any number of crime writers would like to take a shot at writing an epic trilogy. You’ve now done it a few times. Do you have any advice for anyone who’s contemplating spending years of their life on writing a sweeping tale across multiple volumes? I assume your approach for the Danny Ryan trilogy differed from the Border trilogy, for example, just given the sheer amount of research you needed to do for the latter, etc.

Well, I’d tell them to get ready for a marathon. And to understand that it’s life-changing. Other than my wife and son, I have spent more time with Danny Ryan and Art Keller (the protagonist of my other trilogy) than any other real human being in my life. So know that it’s a marriage—you’re going to go to bed and wake up with the same person for decades. I spent 23 years writing about drugs—it changed who I am and how I view the world. I spent close to 30 years wrestling with the Danny Ryan trilogy, it took my going home to Rhode Island and seeing it in a different (more mature?) way to really be able to write the book.

What I would advise above all else is patience. Know that there are going to be good days and bad days on the books, and know that the bad days are absolutely necessary. Those wrong ideas, those crappy pages are an essential part of the process that you just have to go through to get to the good stuff.

I’d also advise flexibility. Don’t get too rigid, too stuck on an outline. Be open to possibilities, go on tangents, because sometimes they’ll open you up things you hadn’t planned or even thought of, and they’re often better than what you had.

You’ve said this will be the last book before you retire. As you look back on your career, if you had to condense your books to a set of themes, what would those be? Throughout your books, your characters inevitably seem to discover there’s a price to whatever they’re doing or desiring. You also tackle everything from the morality of criminality to U.S. policy failures. Is it impossible to condense it down?

Yeah, it’s impossible.

But if you put a gun to my head (I am, after all, a crime writer), I’d say that the central theme that runs through all my work is what I think is the essential question of crime fiction—how do you try to live decently in an indecent world?

When I look back on my career (a relatively recent activity for me) I think that all my main characters have struggled with that issue, whether it was Art Keller trying to reconcile the conflicting morality of the War on Drugs, or Denny Malone navigating the complexities of a cop’s life, Frankie Machine trying to justify his career as a hit man, or Danny Ryan attempting to to raise a family in the midst of a mob war, I think it’s all been about trying to find a morality, or a redemption, in a world that doesn’t care about either. Maybe it’s my Catholic childhood, but those have always been central questions to me, for individuals, societies, even nations. How do we exist decently?

If I find the answer, I’ll let you know.

When you talked to CrimeReads about “City of Dreams,” you seemed pretty adamant about retirement. Is that still the case? As the 2024 election cycle gears up, do you plan on pouring your time into political messaging?

It is still the case.

Look, do I have mixed feelings about it? Of course I do. The readers out there have given me a career and a life that I couldn’t have dreamed of. So I’m grateful. And humbled. And of course I’ll miss it. I already miss that routine of getting up before dawn (okay, I still do that most mornings), making that pot of coffee (ditto) and going to work on a novel (ah, there’s the difference). That was my life.

But we don’t get to choose the times that we live in, and we live in a time in which our democracy is in an existential crisis. That demands our time and energies.

So yeah, watch this space.