Dorothy L Sayers was my gateway author to the world of crime fiction. I’d read the Sherlock Holmes stories earlier on, but that superlatively singular creation of Arthur Conan Doyle did not lead me any further. Holmes was unique, existing in his own universe, and there he remained. Not so with Sayers and Lord Peter Wimsey. The Wimsey family motto is “As my Whimsy takes me,” and Sayers’ whimsy took me right through her books and then onto Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, Josephine Tey, and other authors writing in that great tradition.

My Billy Boyle World War II mystery novels are often set in Great Britian, but it is not the Great Britian of the Golden Age of crime fiction. That Golden Age held sway in the interwar years, 1920 – 1939. But even then, characters like Lord Peter and Harriet Vane represented the values and way of life already shattered by the experience of the Great War. Wimsey has his roots firmly in the nineteenth century. He is graceful upon the page, but it is a grace disguising the transcendental impact of the horror in the trenches and the dreadful thinning of the population of men in so many towns and villages across the country. This is exemplified by Lord Peter’s shellshock, on full display in the first book in the series, Whose Body? where we find him firmly in the grip of vivid nightmares. His world has changed, and all the fine manners and proper deportment he can summon will never bring back the bright, golden days before 1914. In one of her short stories, Sayers has Wimsey declare his own epitaph: “Here lies an anachronism in the vague expectation of eternity.”

Even given this divide between the universe of Lord Peter Wimsey as created by Sayers and the mid-1940s of Billy Boyle and the Second World War, I’d never given up on the notion of finding some sort of intersection between these two worlds. If not a direct connection, then one at least fueled by elements common to both. A homage that, perhaps, only I would recognize.

As I developed the plot for the eighteenth novel in my series, I decided it was time for a change of pace. This entry would be removed from the battlefield and the more exotic locales of the recent books. Since Billy Boyle and friends had never enjoyed any time off, I was overdue to grant them leave. This takes place in the quiet (fictional) village of Slewford in Norfolk, at Seaton Manor, the home of Sir Richard Seaton, father to Billy’s lover, the English spy Diana Seaton.

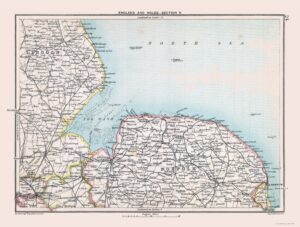

I had to revisit the first book in the series, Billy Boyle, to see where I had originally placed Seaton Manor. For no special reason, I had selected the county of Norfolk, on the east coast of England. Seaton Manor sits near the Wash, a bay and estuary marking a large indentation on the coastline. Tidal forces and shifting sands make the Wash treacherous for those who are unprepared for how fast and swift the tide can come in.

As I studied the countryside around the Wash, it seemed oddly familiar. Then it hit me. This is the Fens, or Fenland, the setting for one of Dorothy L Sayers’ finest works—The Nine Tailors. Her fictional village of Fenchurch Saint Paul is located in Cambridgeshire, just over the border from Norfolk and close to the edge of the Wash. The Fens, a huge expanse of reeds and shallow, freshwater lakes, borders the Wash. Beginning in the seventeenth century, landowners began to drain the Fens in order to turn it into fertile farmland. By Lord Peter’s time, long drainage ditches drew water away from the fields and into the Wash. At the beginning of The Nine Tailors, such a ditch—known as the Thirty-Foot Drain—is exactly where we find Lord Peter Wimsey and his sturdy manservant Bunter.

“That’s torn it!” said Lord Peter Wimsey.

The car lay, helpless and ridiculous, her nose deep in the ditch, her back wheels cocked absurdly up on the bank, as though she were doing her best to bolt to earth, and were scraping herself a burrow beneath the drifted snow . . . right and left, before and behind, the fen lay shrouded. It was past four o’clock and New Year’s Eve; the snow that had fallen all day gave back a glimmering greyness to a sky like lead.

Now I had an intersection. My story of interrupted leave at Seaton Manor also hinged upon treacherous waters. My (first) murder victim was also found in a totally unexpected location, as was the dead gent in The Nine Tailors. Also, I was but a short distance not only from the setting of The Nine Tailors but the home turf of Dorothy L Sayers herself.

Sayers grew up in Bluntisham, Cambridgeshire, right on the edge of the Fens. From 1917 to 1928, her father was the rector at Christchurch, a tiny Fenland village with a notable Victorian church. Here, she would have become familiar with bell ringing, which forms such an important part of the plot for The Nine Tailors. She also would have understood the danger to people living in the Fens from the power of water and tides. The area is kept dry by a series of sluices and floodgates which, on the occasion of heavy rains and high tide, can overflow and wreak havoc.

I already had my own story to tell about treacherous waters and shifting tides. I’d long been fascinated by the Maid of Harlech, which is how locals in Wales refer to an American P-38 Lightning fighter plane that crash-landed just off the coast in 1942. It was only in 2007 that shifting sands and changing tides revealed it, half-buried in the mud. But the sea routinely reclaims it, only to have it appear months later.

With Seaton Manor already established on the east coast, using the Maid of Harlech was out. But I did construct a plot about a German bomber that crash-landed in Norfolk and skidded off a cliff into the Wash, only to have the intense tides reveal it two years later, during Billy’s leave, along with its mysterious cargo. Just as the Thirty-Foot Drain played a key role in The Nine Tailors, so do the tides in Proud Sorrows. I could not resist inserting mention of that drain in reference to a local man brought in to hoist the wreckage out of the water. He comes to the task fresh from dredging the Thirty-Foot Drain.

It’s near impossible to nail down the locations in The Nine Tailors with any certainty. Sayers establishes a firm sense of place without undue worry over precise locations. When Wimsey and Bunter cross the humpbacked bridge and careen off the road, they are in the vicinity of the Sixteen-Foot Drain (the names refer to the width of the canal). We know this mainly from Sayers’ inclusion of actual pubs in the vicinity such as the Dun Cow and the Red Cow. But she transforms the smaller drain into the Thirty-Foot Drain, a much more seriously dangerous waterway.

St. Marys Church, Bluntisham, Cambridgeshire where Dorothy L Sayers spent her early years. The names on some of the gravestones in the churchyard were used in The Nine Tailors. The Reverend Sayers was responsible for beginning a restoration of the church bells at St. Mary’s, which would account for his daughter’s firsthand knowledge of the subject.

St. Marys Church, Bluntisham, Cambridgeshire where Dorothy L Sayers spent her early years. The names on some of the gravestones in the churchyard were used in The Nine Tailors. The Reverend Sayers was responsible for beginning a restoration of the church bells at St. Mary’s, which would account for his daughter’s firsthand knowledge of the subject.

So, I had my intersection with Dorothy L Sayers. Thin, but enough for me. The Fens, the Wash, high waters, and a dead body in the same general vicinity as the corpse in The Nine Tailors. Subtle, but satisfying. What more could I ask for?

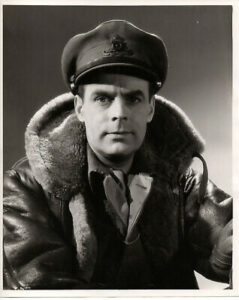

As it happens, one Ian Carmichael. My research turned up the fact that the actor who would portray Lord Peter Wimsey on the BBC from 1972 to 1975 had been an officer in the Royal Armoured Corps during WWII. Carmichael served with the 22nd Dragoons, landing on Juno Beach on D-Day and serving in battles across France, Holland, and Germany.

The 22nd Dragoons was no ordinary unit. They were equipped with specialized Sherman Crab flail tanks. These tanks were modified with heavy chains ending in fist-size steel balls, or flails, attached to a horizontal rotating rotor mounted on two arms in front of the vehicle. They would clear a path through a minefield by slowly driving and flogging the ground ahead of them, exploding the mines. To be effective, the tanks had to drive at no more than one and a half miles per hour, often in the face of enemy fire. That was how Captain Ian Carmichael spent his war.

With that intriguing bit of history tucked up my sleeve, I bring Carmichael onstage. Since the village of Slewford played host to an exclusive POW compound for high-ranking German officers, Captain Carmichael is brought in from the Continent to interrogate a prisoner about German defenses the Dragoons is facing in Holland. He encounters Billy and assists with his investigation, providing yet another Lord Peter intersection.

It would be thirty more years before Carmichael would play Lord Peter, on both radio and television programs. But in 1944, he was close to the age Wimsey is at the time of the novels. I had to work at not letting him slip into the aristocratic patter of Lord Peter, reminding myself that Carmichael was an aspiring actor from northern England, the son of an optician, not the Duke of Denver.

Still, I did let a bit of Wimsey slip through. After reading Carmichael’s delightfully witty autobiography, Will the Real Ian Carmichael, I tried to adapt his breezy tone. Perhaps it was an affectation he developed over the years, but it fit him so well, I did my best to be true to it. He was great fun to write.

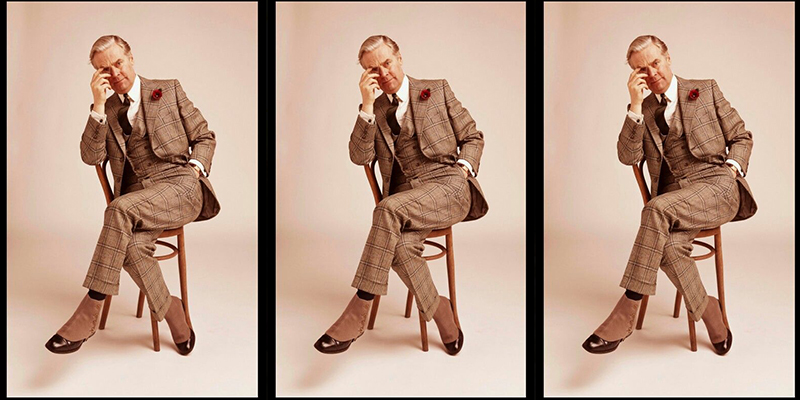

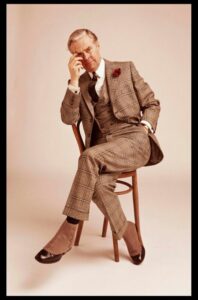

Ian Carmichael as Lord Peter Wimsey. He was often photographed with his left hand in a pocket, having lost the tip of one finger in an encounter with a heavy tank hatch.

Ian Carmichael as Lord Peter Wimsey. He was often photographed with his left hand in a pocket, having lost the tip of one finger in an encounter with a heavy tank hatch.

For those fans of Dorothy L Sayers who prefer Edward Petherbridge as their Wimsey (he starred in several BBC productions during the 1980s), I can only report that he was a mere eight years old in 1944, far too young to have any role in investigating the murders in Slewford.

***