If you’ve read any self-help before, then you know that most of it reads like a 90-percent redacted NSA document obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request—all the most salient details blacked out, unavailable. Exactly how many nannies, for instance, did it take for Sheryl Sandberg to Lean In? If the Rich Dad, Poor Dad guy is such a financial genius, how come he shills real-estate seminars? And if Rachel Hollis really knows how to have a successful, sexy marriage, why’d she get divorced? Their books promise answers to life’s biggest questions, only to leave us with bigger questions.

Yet why we buy and read such books is no mystery. Shit’s hard. Life can be a relentless grind. We go through tough moments, individually and collectively, and we need encouragement, some clue about “how to stand up,” in John Berryman’s phrase. Where demand meets supply, however, is where a brackish river of hope and greed flows into an ocean of bullshit. The problem isn’t self-help as a genre—few genres make more natural sense than how-to—or even with individual self-help gurus, some of whom mint millions from their shiny slogans and toothy smiles.

No, the real problem is that no one can tell the whole truth about their life, at least not while they’re breathing. If an author’s still alive, then they themselves don’t know whether they’re living a success story about the triumph of the human spirit, or a dark cautionary tale about comparing yourself to Harriet Tubman on Tiktok, bringing the larger girlboss industry down with you (so perhaps doing some good after all?).

Literary biography serves our need for wisdom much better. Inside its thick, carefully researched and diplomatically worded volumes, you get the dirt—the horrifying marriages, the drinking, the grandiosity even at breakfast. You witness, in other words, how those who achieve literary greatness tend to be huge messes. Think of Jean Rhys or Anne Sexton, Malcolm X or James Dickey: messes, all. Often, you also glimpse a legit redemptive arc, free from the toxic positivity that shapes most narratives, self-help or otherwise. It follows that the saddest literary lives present the most arresting hope, the most powerful examples of how to transcend one’s circumstances. Of how to stand up, as a writer and a maybe as a person, too.

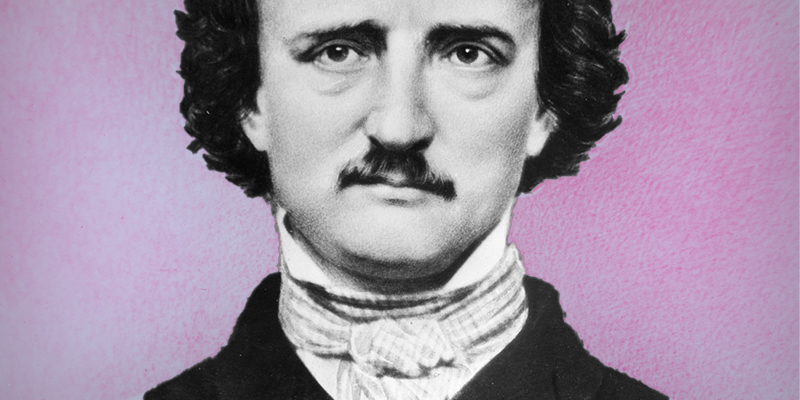

And if there was a sadder literary life than Edgar Allan Poe’s, well, you tell me. His career of poverty, loss, disappointment, and unmerciful disaster could rival any wretch’s in history. A writer of modest achievement would stand out against this biographical backdrop; Poe’s achievement is the opposite of modest. No other American writer has an NFL team named after one of their poems, or ever did as much to inspire the novel Lolita, which reads like a 300-page burlesque of “Annabel Lee” and a grotesque in Poe’s own vein. Ask the average layperson to name three writers, and chances run about 100% that one of those three writers will be Poe, probably alongside Mark Twain and J.K. Rowling or John Grisham. Tens of millions of people could identify Poe in a police line-up. The scale of his success strains credulity, begging the question of whether human misery might, despite everything, have meaning.

This is why, in American culture and beyond, Poe’s life story has pretty much risen to the level of myth, so that only an anthropologist, not a biographer, could ever properly explain his impact. Take a step back and squint, and Poe can seem an invented personality like Santa Claus, an egregore standing in for our widespread conviction that artists may be existential saints. If he hadn’t existed, we’d have had to invent him.

In a way, we did invent him. Poe biography is a haunted palace echoing with endless disputes. It’s not just that the historical record is patchy, either. As most fans know, he was first the subject of an absolute hit job of an obit, written by Rufus W. Griswold, his great frenemy and a jealous, credential-faking sleaze par excellence. Griswold would up the ante with a longer, even more slanderous biography. Yet somehow even this slander served Poe, providing irresistible PR that’s persisted well into our own time, and drawing no less than Charles Baudelaire into the sinner-or-saint debate. He’d become Poe’s most articulate champion, and we could all do a lot worse than be celebrated by a writer of Baudelaire’s stature.

“There are fatal destinies—there exist in the literature of each country some men who bear the words bad luck written in mysterious characters in the sinuous folds of their foreheads,” wrote Baudelaire, whose sinuous defenses of Poe would be collected and published in English as Fatal Destinies. The tortures these souls endure exists for the “edification of others,” Baudelaire argues, and “if you carefully follow their lives, you will discover their talents, their virtues, their grace.” With Poe, even the heavy drinking was “a method of work.”

But like anyone who veers into Poe hagiography, I had the experience of the epiphany—that Poe was a hero—before I discovered the longer tradition. A few years ago, midway through my life’s journey, I found myself in a dark wood, and I started rereading Poe for the first time since I was a kid. What was it that made me reach for The Complete Tales of Mystery and Imagination at a moment when I could see no way forward, so that I cracked the volume and read the first phrases of “The Pit and the Pendulum,” namely, “I was sick—sick unto death with that long agony,” suddenly understanding the story as metaphor? I don’t know. A benevolent nudge from the universe, or something.

It was late 2016, and it felt like the lights were going out all over. Looking back now, I see how I was groping for something to read that would be dark enough to match my mood but that wasn’t just more depressing news. It was a relief to fall under Poe’s spell, to spend time with someone whose life also took place in an absurdly depressing era. The angel of the odd, against all odds, bucked me up. His poetry and fiction had an effect akin to what Bruno Bettelheim, in The Uses of Enchantment, says about fairy tales—imparting a sense that, while existence may present us with all manner of problems and danger, we have it in us to respond.

I’d worry about extrapolating too much, evangelizing about a personal experience that might not be applicable to other lives, but I know now I’m not the only person who’s had this experience. My sense, after spending so long in Facebook fan groups dedicated to Poe, watching members endlessly share how they’ve been inspired by him, is that many others have had the same experience. It’s just that the view hasn’t really been articulated in this country.

The evidence of our response is everywhere: the internet teems with fan art, showing Poe’s effect on countless tattooists, plus amateur poets, painters, and playwrights. William Carlos Williams did mount a deeply idiosyncratic defense with In the American Grain; no wonder it hasn’t been much read. So Poe’s effect on us is plain enough, but try to account for it, and you’ll encounter a strange gap, at least in English. Where’s the pop self-help book based on Poe’s life and work, showing us how to emulate his perverse success?

I would say this, having written that book, but the moment has come. A spate of news stories since early 2020 have used Poe to interpret our own era. We might go one step further and see him as an antidote to toxic positivity, offering more grounded hope than the conventional self-help fare. There’s no better time to reread him than now, or let him reassure you, via his biography, that art and beauty may grow out of your personal hell. You may have one of those duck/rabbit experiences in which you can actually feel your perspective change, like I did.

How can one person inspire so much, boast this kind of range and influence? What’s his secret? Don’t you want to know?And boy, are the details of his life messy, enough to make you feel better about whatever you’re going through. Poe is often considered a creature “out of SPACE—out of TIME.” But he was very much a man of his era, identifiably antebellum, down to the profound racism and sexism. That Poe still feels so contemporary is because of the bizarre historical rhyme in which his Jacksonian experience overlaps with millennial experience—coming of age amidst a dire recession, in a chaotic information age, with crippling student debt, limited access to healthcare, and a whiff in the air of civil war.

Poe also feels contemporary because of the epic, ongoing story of his interpretation, the way every new generation reconstitutes him in their own image. Even this is moving, a strangely beautiful spectacle. The guy, with his sometimes-unspeakable politics, is said to have influenced Spanish-language literature more than any other American author, and filmmakers from George A. Romero to Jordan Peele have brilliantly reimagined his work for fresh audiences. Poe is a cottage industry now in the literal sense, with four different houses and museums dedicated to his memory, as well as festivals, conferences, t-shirts, coffee mugs, home-office décor, and an entire academic discipline known as Poe Studies. I’ve been researching Poe for over four years, and I’m still coming across new allusions, references, presences: Poe’s cameo on Gumby. An original 90210 episode named for “The Pit and the Pendulum.” His outsize status in Romanian literature.

How can one person inspire so much, boast this kind of range and influence? What’s his secret? Don’t you want to know?

Even so, I keep getting the journalistic equivalent of weird looks as I launch my book and work the podcast circuit, and this when I’m not the first person to make the case for Poe as an existential hero, a suffering saint of the arts. Arguably a whole country got there first.

According to Joan Fiedler Mele, who translated Fatal Destinies, French schoolchildren grow up reading Baudelaire’s Poe essays. It’s more widely known that Poe enjoys French popularity along the lines of Jerry Lewis. Which means that a self-help reading of Poe is not only arguably overdue, but comes with some handy French imprimatur, a la Pamela Druckerman’s Bringing Up Bébé or Mireille Guiliano’s more controversial French Women Don’t Get Fat.

Baudelaire, in fact, went so far as to pray to Poe, and he suggested we do the same. “All of you who have eagerly sought to discover the laws of your being, who have aspired to the infinite, and whose repressed emotions have had to seek frightful relief in wine and debauchery, pray for him,” he wrote. “Now his purified, corporeal being swims among those whose existence he foresaw, pray for him who sees and who knows, he will intercede for you.”

It worked for Baudelaire, too. He died in his 40s, syphilitic and destitute, but he’d done his work. Poe worship is, in other words, a proven formula. A tried and tested Poe-gram. I recommend it. You should try it. It could change your life.

***