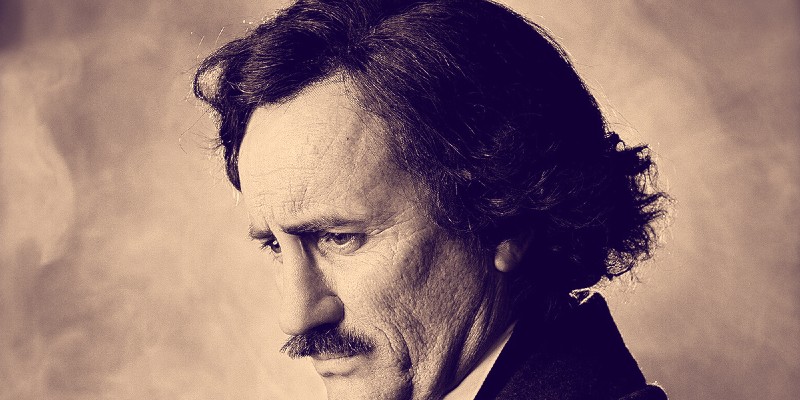

“The trial of Polly Bodine will take place at Richmond, on Monday next, and will, no doubt, excite much interest,” wrote Edgar Allan Poe on June 18, 1844, for the Columbia Spy.

Poe had recently moved to New York where, he declared, “I intend living for the future.” He got a temporary lift when he sold “The Balloon Hoax” story, a fictional account of the first transatlantic balloon crossing to Moses Yale Beach of the Sun. THE ATLANTIC OCEAN CROSSED IN THREE DAYS!! screamed the Sun in April 1844. James Gordon Bennett exposed Poe’s story as a hoax and Beach issued a retraction. Not even the Sun could hold its readers entirely on hoaxes.

Soon, Poe was broke again. He found a city of strangers and ran up debts. Poe lamented that in America “to be poor is to be despised.” In May 1844, he got work as a correspondent for the Columbia Spy for which he wrote epistles on “the Doings of Gotham.” Poe spent that summer “roaming far and wide over this island of Mannahatta” to chronicle the city.

But he kept pitching stories to magazines, always searching for the commercial success that had eluded him. For years, Poe had read with fascination the penny press’s reports on murder investigations, and this sparked a notion in him: perhaps he could solve cases through the newspapers? Indeed, he might even be better at crime-solving than the authorities.

In 1841, Poe wrote “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” his groundbreaking detective story featuring Monsieur C. Auguste Dupin, an amateur sleuth in Paris who unravels crimes through “ratiocination,” the application of deductive logic to the clues. Monsieur Dupin reads in the newspapers about the savage murders of two women. He explains to his sidekick that the police focus too narrowly on the rules of evidence. “This may be the practice in law, but it is not the usage of reason. My ultimate object is only the truth,” he insists. Dupin deduces that the killer was . . . an orangutan that’d escaped from a sailor’s possession. The story concludes with Poe’s defense of amateur crime-solving. “The Chief of police was not happy that the answer to the mystery of the killings had been found by someone who was not a policeman,” says his sidekick. Dupin replies that while the chief is a “good fellow” he often misses “something which is there before his eyes.”

Then a real murder captured Poe and the public’s imagination. On the sweltering morning of July 28, 1841, passersby spotted a woman’s corpse floating on the Hudson River. The victim was Mary Cecilia Rogers, a beautiful, twenty-one-year-old “cigar girl” at John Anderson’s tobacco emporium. The Herald speculated that she was killed by a “gang of negroes.” The Post reported that an Irish gang lured Mary Rogers to the shore where she was, “after the accomplishment of their hellish purposes, brutally murdered.”

Dissatisfied, Poe did something audacious: he set out to publicly solve the Mary Rogers case while the investigation was ongoing. He pitched a new, thinly veiled Monsieur Dupin detective story in which he would reanalyze the Mary Rogers case and reveal the real killer. “I believe not only that I have demonstrated the fallacy of the general idea thinly-veiled—that the girl was the victim of a gang of ruffians—but have indicated the assassin in a manner which will give renewed impetus to the investigation,” he promised his editor.

“The Mystery of Marie Rogêt” was serialized in William Snowden’s Ladies’ Companion. Dupin explains to his sidekick how he intends to solve the crime. “Not the least usual error, in investigations such as this, is the limiting of inquiry to the immediate, with total disregard of the collateral or circumstantial events,” he explains. “It is the malpractice of the courts to confine evidence and discussion to the bounds of apparent relevancy.” While the prevailing theory was that Marie had been the victim of gang, Dupin deduces that the killer was a naval officer.

Developments in the actual Mary Rogers case threatened to destroy Poe’s theory. Two sons of Mrs. Frederica Loss, an innkeeper, were arrested on suspicions that they’d murdered Mary Rogers at the inn. Mrs. Loss confessed on her deathbed that Mary had come to the inn with a physician for an abortion, but she died from the botched abortion. Neither scenario squared with Poe’s theory that it was a naval officer. Faced with public humiliation, Poe drank heavily. By the time of the final installment, he came up with a literary trick. Dupin debunks the gang theory. But just as he’s about to reveal the perpetrator, there is a supposed note from the editor which states that, for legal reasons, “we have taken the liberty of omitting” information about the real killer.

Today, Poe is credited with establishing the modern detective genre in his Monsieur Dupin stories. But his stories celebrating amateur detectives portended something else as well. In trying to publicly “solve” the real Mary Rogers case through dramatic storytelling, Poe was the forerunner to the “true crime” documentarians of our own time. He believed that outsiders could solve cases which have baffled or misled the authorities. When he vowed to “give renewed impetus to the investigation,” we can hear echoes of documentarians of today who seek to reopen moribund cases, or to free those whom they believe were wrongfully convicted. Like Poe, they’ve had mixed success.

By the time of the trial of Polly Bodine that summer of 1844, Poe was in full bloom as a crime writer. His classic short stories “The Tell-Tale Heart” (1843) and “The Black Cat” (1843) imagined killers as unnamed narrators. The morbid details of “The Oblong Box” (1844) were inspired in part by John Colt’s attempt to ship the corpse of Samuel Adams. That summer, he also sold “The Purloined Letter” (1844), his third and final detective story featuring Monsieur Dupin. 8 So it was inevitable that Poe would weigh in on the real case that seized the nation that summer.

“The trial of Polly Bodine will take place at Richmond, on Monday next, and will, no doubt, excite much interest. This woman may, possibly, escape; for they manage these matters wretchedly in New-York,” he wrote. Trial testimony hadn’t even begun. But the initial press reports were enough for him to deduce that Polly was plainly guilty.

The Polly Bodine case had stirred up in him old feelings about the Mary Rogers debacle. “It is difficult to conceive anything more preposterous than the whole conduct, for example, of the Mary Rogers affair,” Poe wrote. “The police seemed blown about, in all directions, by every varying puff of the most unconsidered newspaper opinion,” he said. “The magistracy suffered the murderer to escape, while they amused themselves with playing court, and chopping the technicalities of jurisprudence.” His column also resurrected arguments from “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” that “very much of what is rejected as evidence by a court, is the best of evidence to the intellect.” Poe ended with a tantalizing prediction about how the rules of evidence might affect the pending trial. “I have good reason to believe that it will do public mischief in the coming trial of Polly Bodine,” he wrote. What crucial evidence did Poe think would be excluded? What “mischief” did he think would occur in the coming trial?

___________________________________