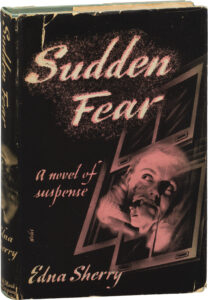

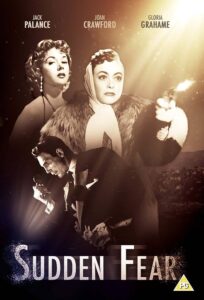

For decades American novelist and playwright Edna Sherry, author between 1948 and 1965 of nine crime novels, has essentially been viewed as a one-work writer, based on the terrific success of her nail-biting 1948 crime novel Sudden Fear, or more truly its hair-raising 1952 film adaptation, which starred Joan Crawford, Jack Palance and Gloria Grahame and, unusually for a crime drama, netted four Oscar nominations, including in the leading and supporting acting categories, respectively, for Crawford and Palance. (Grahame that year was nominated—and won—in the supporting actress category for the satirical drama The Bad and the Beautiful.) Although the film lives in a spiffy 2016 Blu-ray DVD edition, the novel, oddly, has remained out-of-print for over six decades, and the rest of Edna Sherry’s crime legacy has, until recently, been forgotten. It seems a surprising state of affairs, but then Edna Sherry herself was largely a mystery woman, rigorously avoiding publicity for herself and her family. In this endeavor she was largely successful, with a notable exception, as we shall see, involving her only son, Ernie.

First, let us take a look at the life and crime writing career of Edna Sherry. She was born Edna Solomon in Cincinnati, Ohio on November 28, 1885, one of four children of Michael and Sally Solomon, native Prussian Jews. After the Civil War Michael Solomon had moved to Cincinnati, Ohio from New York City, where his father had been a tailor, and there had set himself up as a dealer in gentlemen’s neckwear. Having married Louisville, Kentucky native Sally Levy and prospered substantially in the Cincy haberdashery trade during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Michael Solomon at the century’s turn moved with his family to Manhattan, where he lucratively took up real estate brokerage.

First, let us take a look at the life and crime writing career of Edna Sherry. She was born Edna Solomon in Cincinnati, Ohio on November 28, 1885, one of four children of Michael and Sally Solomon, native Prussian Jews. After the Civil War Michael Solomon had moved to Cincinnati, Ohio from New York City, where his father had been a tailor, and there had set himself up as a dealer in gentlemen’s neckwear. Having married Louisville, Kentucky native Sally Levy and prospered substantially in the Cincy haberdashery trade during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Michael Solomon at the century’s turn moved with his family to Manhattan, where he lucratively took up real estate brokerage.

Edna attended Hunter College (then a women’s college) in Manhattan and was awarded a degree in English from that institution in 1906. For three years after her graduation she was employed as an English teacher, but she left the teaching profession in 1909 after wedding Ernest Thomas Sherry, a dentist a decade older than she who came originally from Eydtkuhnen, East Prussia (today Chernyshevskoye, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia). Ernest Sherry—a German native and presumably an ethnic Jew like Edna—was stated in newspapers to have been an elder brother of famed restauranteur, hotelier, caterer and confectioner Louis Sherry, whose renowned luxury chocolates still are sold today, although ostensibly the latter Sherry was not of German but rather French-Canadian descent. Had Louis Sherry, who grew rich from literally catering to the pleasures of New York’s Gilded Age millionaires, attempted to obscure German-Jewish origins? The surname Sherry belongs to multiple nationalities and ethnicities, including the Hebraic. For example, the late 1959 baseball World Series MVP Larry Sherry, a pitcher for the LA Dodgers, was a Jew, like his better-remembered teammate Sandy Koufax. Whether or not Ernest and Louis Sherry indeed were Jewish that the two men were siblings was deemed a fact in the press.

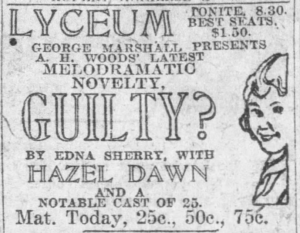

After their marriage Ernest and Edna took up residence in Manhattan at a swanky apartment building on 54 Riverside Drive. The couple had two children, Ernest and Phyllis, and, completing the composition of the household, there was as well a live-in, native Hungarian cook. After more than a decade of marriage and motherhood, Edna, doubtlessly inspired by the massive stage success of The Bat (1920) and The Cat and the Canary (1922), made a stab at literary fame with her own mystery play, which she entitled Guilty? The play was purchased in 1923 by prominent Jewish native Hungarian theatrical producer Albert Herman Woods (formerly Aladore Herman), who had recently produced the hit sex farces Ladies’ Night (1920) and The Demi-Virgin (1921) and would go on to produce the hit courtroom mysteries The Trial of Mary Dugan (1927) and Night of January 16th(1935), the latter of which was written by mystery devouring philosopher Ayn Rand. Edna seemingly was in good hands with A. H. Woods.

Guilty? was tried out on March 5, 1923 at Baltimore’s Lyceum Theater by the George Marshall Players in a production starring lovely silent film actress Hazel Dawn and dashing English actor Henry Daniell, the latter of whom went on to a distinguished film career of over three decades’ duration, which for mystery fans included a definitive turn as wicked Professor Moriarty in the Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes film The Woman in Green (1945). A review of Guilty? in the Baltimore Sun deemed the play’s dialogue “stilted and unconvincing” but pronounced Sherry’s plot “remarkably good” and concluded that the play held considerable promise if revisions were made. While headliner Hazel Dawn was panned, Henry Daniell drolly was singled out for praise for acting his part of the “neurotic artist” with “grace and finesse” despite “being killed three times during the performance.” Sadly for Edna Sherry, however, the production’s electrician turned the play into something of a comedy by repeatedly turning on the lights while the hands were still on stage shifting scenes, inducing from the audience “roars of laughter” as startled men rushed “for elusive exits.” The play died a quick death in Baltimore.

Undaunted, Edna Sherry kept writing. She published a couple of short stories, “The Crimson Girl” (1937) and “Strange Cargo” (1928), in the pulps in collaboration with Charles Kassel Harris, the popular Jewish sentimental songwriter (“After that Ball,” etc.) who with the rise of silent films moonlighted as a movie scenarist. However, Edna scored her first real literary successes in 1929 in collaboration with Milton Herbert Gropper, a once-noted, handsome playwright and screenwriter of Rumanian Jewish derivation who, though a decade younger than Edna, had already had a half-dozen plays performed on Broadway, including the provocatively-titled hit Ladies of the Evening (1924), which was adapted by director Frank Capra as the hit 1930 film Ladies of Leisure, starring a youthful Barbara Stanwyck.

The first of Milton’s and Edna’s collaborative successes—Milton is credited with dialogue and Edna with the story—was Through Different Eyes, a courtroom murder melodrama innovatively told in a series of flashbacks from multiple perspectives, in anticipation of the great 1951 Japanese film Rashomon. Milton’s and Edna’s Eyes, which was originally available in both silent and newfangled talking versions (regrettably the “talkie” version since has been lost) and marked the first significant film appearance of actress Sylvia Sidney, was well-received by critics. In a long, laudatory notice in the New York Times, film critic Mordaunt Hall praised Eyes as an “ingeniously conceived murder trial story, one that lends itself to three different shadings of the leading characters.”

Later that year Milton’s and Edna’s locked room mystery play Inspector Kennedy (also known as Homicide) premiered on Broadway at the Bijou Theater. Although the play, which was packed to its melodramatic rafters with “a police inspector and a number of detectives, a leader of a dope ring, secret panels, a couple of mysterious murders and [several] men and women with motives that might have prompted them to commit the crimes,” ran at the Bijou for only forty-three performances between December 20, 1929 and January 25, 1930, it was successfully taken on the road, with productions staged in Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Wilmington, Boston, and Windsor, Ontario, among other locales. The title role of Inspector Kennedy was played, in his penultimate performance before his retirement, by hugely popular “road” actor William Hodge, who also directed the play. Of Hodge the New York Times noted, at his death in 1932: “‘The William Hodge public’ was a Broadway phrase meaning that whether or not the Hodge plays were successful in New York…he could be sure of a keen response almost anywhere in the country.” Striking while the bloody poker was hot, Milton and Edna novelized the play in 1930 under the catchy title Is No One Innocent?, altering the stage play’s solution to the murder.

Oddly, eighteen years elapsed before Edna Sherry, who was now sixty-three years old, published her first solo crime novel, Sudden Fear, to nearly universal acclaim. “I unhesitatingly pronounce Sudden Fear…the best mystery novel which has come forth from a publishing house in the past year or more,” gushed E. D. Lambright, editor of the Tampa Tribune, adding that the novel was “a one-sitting book—one that you will not put down until you have finished the last chapter, the last paragraph.” Dorothy B. Hughes, herself a crime writer of great critical repute, affirmed (in the Albuquerque Tribune), “You’ll race through the pages [of Sudden Fear], the suspense is that terrific,” as did the Boston Globe’s Avis De Voto, who avowed: “[Sudden Fear] packs a wallop that will haunt you.”

Oddly, eighteen years elapsed before Edna Sherry, who was now sixty-three years old, published her first solo crime novel, Sudden Fear, to nearly universal acclaim. “I unhesitatingly pronounce Sudden Fear…the best mystery novel which has come forth from a publishing house in the past year or more,” gushed E. D. Lambright, editor of the Tampa Tribune, adding that the novel was “a one-sitting book—one that you will not put down until you have finished the last chapter, the last paragraph.” Dorothy B. Hughes, herself a crime writer of great critical repute, affirmed (in the Albuquerque Tribune), “You’ll race through the pages [of Sudden Fear], the suspense is that terrific,” as did the Boston Globe’s Avis De Voto, who avowed: “[Sudden Fear] packs a wallop that will haunt you.”

One of the entranced readers of Sudden Fear, so the story goes (this came straight from the horse’s mouth, as it were: entertainment columnist Louella Parsons), was Oscar-winning actress Joan Crawford, who upon reading Edna Sherry’s debut solo novel in 1950 saw in the story of an accomplished middle-aged woman playwright who rashly marries a much younger—and much scheming—actor, a fine vehicle for her histrionic talents, which had been honed since the silent film era. Crawford also served as the film’s executive producer, and the result was a creative triumph both for the actress and the novelist.

The well-acted, smartly scripted, beautifully shot, evocatively scored and superbly suspenseful film was directed by David Miller, who would later helm another popular woman-in-peril thriller, Midnight Lace (1960), starring Doris Day and Rex Harrison; photographed by Oscar-winning cinematographer Charles Lang, who shot such thriller classics as The Cat and the Canary (1939), The Ghost Breakers (1940), The Uninvited (1944), Charade (1963) and Wait Until Dark (1967); co-scripted by Oscar-nominated screenwriter Lenore Coffee, who back in 1929 had written the talking film adaptation of S. S. Van Dine’s bestselling Philo Vance mystery The Bishop Murder Case, starring Basil Rathbone; and scored, in just his third filmic outing, by a young Elmer Bernstein, himself a future Oscar winner.

The well-acted, smartly scripted, beautifully shot, evocatively scored and superbly suspenseful film was directed by David Miller, who would later helm another popular woman-in-peril thriller, Midnight Lace (1960), starring Doris Day and Rex Harrison; photographed by Oscar-winning cinematographer Charles Lang, who shot such thriller classics as The Cat and the Canary (1939), The Ghost Breakers (1940), The Uninvited (1944), Charade (1963) and Wait Until Dark (1967); co-scripted by Oscar-nominated screenwriter Lenore Coffee, who back in 1929 had written the talking film adaptation of S. S. Van Dine’s bestselling Philo Vance mystery The Bishop Murder Case, starring Basil Rathbone; and scored, in just his third filmic outing, by a young Elmer Bernstein, himself a future Oscar winner.

Rarely has a mystery writer enjoyed such a felicitous translation of her work onto film as did Edna Sherry with Sudden Fear—though it was not in fact the author’s first time at the cinematic rodeo, recalling Through Different Eyes from nearly a quarter-century earlier. Perhaps as a result of her financial independence (her husband was very well off and she had inherited $10,000, or $200,000 in modern worth, from her late father in 1934), Edna was slow, however, to follow up on the film’s success. In 1949, she had published another crime novel, No Questions Asked, but it was not until 1956, four years after Sudden Fear’s cinematic debut, that she produced a third crime novel, Backfire.

Afterward, however, her crime novels (all of which were published, like her other solo novels, by Dodd, Mead in the United States and Hodder & Stoughton in the United Kingdom) came at a rapid clip: Tears for Jessie Hewitt (1958), The Defense Does Not Rest! (1959), The Survival of the Fittest (1960), Call the Witness (1961), Girl Missing (1962) and, lastly, Strictly a Loser (1965). This final novel appeared a year after the death of Edna’s husband Ernest at the age of ninety and less than two years before her own death in New York City on February 4, 1967, as the age of eighty-one. While she never replicated the success of Sudden Fear, Edna Sherry produced a worthy body of crime fiction, largely in the “inverted” mystery form, that now is being belatedly rediscovered.

No less a judge—and a cranky, hanging one at that—than British crime writer Francis Iles (aka Anthony Berkeley Cox), author of the classic inverted mystery Malice Aforethought (1931) and suspense novel Before the Fact (1932), praised Edna Sherry’s valedictory essay in the form, Strictly a Loser, as something that was rather the opposite of its title. Although a product of the United States, the intensely nationalistic Iles noted, Edna’s novel was composed “in blessedly straight-forward English” and was “a good, uncomplicated story about a ruthless young woman who does not shrink from murder to further her own interests.” At the end of his review Iles fearfully wondered: “Are there any real Susan Caldwells in this world? One hopes not. But Miss Sherry makes us feel there could be.” Ultimately it is this frisson of fear which Edna Sherry induces in the reader—this apprehension of murder—that is the signal quality of her crime fiction, from Sudden Fear through the rest of its killing company.

*******

Given her success in the field of a crime fiction, Edna Sherry seems to have been remarkably publicity-averse. It is as if having gotten away with her fictional crimes, as it were, she did not want to risk any personal exposure. In the course of my researches on the author, I have discovered not one single photo of her or any newspaper interview. Why this vanishing act, this deafening silence? Why around 1930 did she stop writing for almost two decades? Let me offer my theory.

However much Edna Sherry may have led a hole and corner existence in the heart of Manhattan, her only son, Ernest Thomas Sherry, Jr., managed once, to the great regret of his parents, to make the national news in a big way. This was in 1930, not long before Edna’s fellow New York crime writer Cornell Woolrich was similarly embroiled, like young Ernest, in a marriage annulment scandal; and perhaps this affair contributed to Edna’s pronounced case of wallflowerism, a rare malady indeed among self-seeking crime writers.

During the summer of 1930 the story spread around the country like a rumor of war, via salacious newspaper daily headlines and Sunday pictorial supplements: eighteen-year-old Ernest Sherry, Jr., the “playboy” nephew of the late millionaire Louis Sherry and son of a wealthy dental surgeon on Riverside Drive, had gotten himself embroiled in a novel matrimonial pickle, one that was unique even in a sexually jaded metropolis that had been routinely diverted by the madcap social tumults of the Roaring Twenties. There were, you see, these two pretty young sisters, Audrey and Nedra Baker, aged respectively twenty and nineteen in January 1930, when they made the acquaintance of Ernie Sherry, as he was familiarly known. Like characters in a Cornell Woolrich story, the Baker sisters had come to New York from the small factory city of New Castle, Pennsylvania, the so-called “tin plate capital of the world,” hopefully seeking their fame and fortunes, despite their modest circumstances. Their father, Harry Baker, worked as a roller in New Castle’s tin mill.

During the summer of 1930 the story spread around the country like a rumor of war, via salacious newspaper daily headlines and Sunday pictorial supplements: eighteen-year-old Ernest Sherry, Jr., the “playboy” nephew of the late millionaire Louis Sherry and son of a wealthy dental surgeon on Riverside Drive, had gotten himself embroiled in a novel matrimonial pickle, one that was unique even in a sexually jaded metropolis that had been routinely diverted by the madcap social tumults of the Roaring Twenties. There were, you see, these two pretty young sisters, Audrey and Nedra Baker, aged respectively twenty and nineteen in January 1930, when they made the acquaintance of Ernie Sherry, as he was familiarly known. Like characters in a Cornell Woolrich story, the Baker sisters had come to New York from the small factory city of New Castle, Pennsylvania, the so-called “tin plate capital of the world,” hopefully seeking their fame and fortunes, despite their modest circumstances. Their father, Harry Baker, worked as a roller in New Castle’s tin mill.

In New York Nedra became an industrious mannequin, or model, at a dress factory, while her more voluptuous, butterfly elder sister Audrey, after graduating from the dancing school of Ned Wayburn, choreographer of the Ziegfeld Follies, was hired as one of the “little girls” (i.e., a chorine) at one of the speakeasies run by the notorious Mary Louise “Texas” Guinan, the Prohibition Era’s so-called “Queen of the Nightclubs.” Certainly Audrey’s classmates at New Castle High School had known that the girl had “it” (whatever “it” was), rhymingly declaring of her, next to her glamorous photo (complete with corsage and spit curl) in the senior annual:

She never misplaces her lipstick;

Her eyes often work overtime.

As a dancer and leader of fashion,

This maiden is simply sublime.

At Texas Guinan’s place Audrey was a bright flapper flame who attracted many a persistent male moth, including young Ernie Sherry. Soon tiring of his attentions, as she later told the newspapers, she palmed Ernie off on her shyer, accomodating sibling Nedra, with whom she shared an apartment. Poor, overworked Nedra, it seems had had “little opportunity to meet gentlemen” since moving to the big city. Impressionable Ernie quickly proposed marriage to Nedra and she accepted.

Yet when the day arrived on January 22 for the couple to pay a visit to the city clerk’s office and be lawfully wed, Nedra found that that her heartless employers would not grant her time off to do the deed. Happily, or so it seemed at the time, Audrey obligingly offered to act as a stand-in for her sister at the city clerk’s office, giving her name as Nedra, saving her younger sister the trouble of actually appearing herself as Ernie’s chosen bride. Ernie deemed this a topping idea and together he and Audrey persuaded the more skeptical Nedra to go along with the scheme. The ceremony thereupon took place as planned and afterward Audrey delivered the marriage certificate and Nedra’s new “husband” to her. Ernie and Nedra honeymooned in Montreal, Canada and lived together for several months as man and wife before the bloom came off the matrimonial rose and the disenchanted young couple decided to sever their union.

Ernie went home to his parents, incidentally explaining the actual circumstances of his “marriage” to them. His dismayed father promptly consulted a lawyer and after said consultation placed a phone call to Audrey explaining that she, not Nedra, was his son’s legal wife. Now the fat was in the fire and sizzle it surely did, to the anticipatory salivations of New York’s sensation-hungry press corps, to whom Audrey, evidently loathe to miss a good piece of publicity when she saw it, gave extensive interviews, accompanied by numerous glamor photos of herself.

Questions rattled in the newspapers like skeletons in drafty closets. Would young Ernest, who though the scion of a wealthy father who himself was employed in a twenty dollar a week clerking job (in today’s dollars about $16,000 a year), owe alimony to Audrey, who had no intention of staying married to him? Could Nedra actually now be deemed the common law wife of Ernest? Had Ernest in fact committed bigamy? Would he owe both of the sisters alimony? The demoralized Ernie exasperatedly confided to the press his blunt view of the perplexing affair, avowing: “The quicker this thing is finished, the better. I’m sick and tired of the pair of them. I guess I was a fool, all right.”

As would happen in the case of Cornell Woolwich, Ernie’s official wife (Audrey) brought a successful annulment suit against her legal husband, asserting that the union had never actually been consummated. What further arrangements, if any, were made among the parties was not divulged in the newspapers. The sparks of the story, which had exploded in newspapers like a firecracker on the Fourth of July, faded fast with the summer season, although the next year a newspaper dramatically reported that “[b]lackmailers are trying to make things real mean for young Ernest T. Sherry, scion of the wealthy Sherry family of New York City, the man who married Audrey Baker…when he had every intention of marrying her sister, Nedra.” It seems that $10,000—the same amount as Edna’s future inheritance from her father—was being demanded from the impetuous youth if he desired to avoid further embarrassing “love publicity.” However, Ernie—or, presumably, his parents—decided that, rather than fork over the dough, he would put a team of private detectives on his would-be extortionists’ trails. Apparently this action frightened away further predators.

Audrey had another publicized encounter of an amatory kind, admittedly an occupational hazard of an attractive Thirties chorus girl. In September 1930, just after the dust had settled in the Sherry affair, Audrey was back in the news, having accused thirty-year-old “Broadway playboy” Rudolph Carl Bergstrom, a native Swedish Long Island real estate broker and president of Queens Garden Homes, Inc., of blacking her eye when she resisted the passionate advances he made upon comely person in an automobile. Recalling the Sherry imbroglio, two other unnamed women came forth soon afterward with similar claims against Bergstrom, who had also recently figured as the co-respondent in a husband’s divorce suit. The outraged broker decried the assault accusations as “shakedown attempts” on the part of a trio of designing women.

The outcome of all this back and forth recrimination went unreported, but the New York Daily News left its readers with a truly memorable newspaper headline: Police Quiz Guinan Girl in Whoopee Ride Attack Charges. (This surely is something that you do not read every day.) Five years later, Bergstrom committed suicide by shotgun blast in a locked room at a cheap hotel, inadvertently nearly slaying a hapless workman in the hallway in the process. Bergstrom left a much depleted “fortune” of $150 in bills which he had sealed in an envelope cryptically addressed to an “Anna Smith.” Fittingly, two different women came forward to claim the money. Nedra Baker died in 1988, apparently never having married (legitimately), while Audrey survived until 1999, expiring a day after her ninetieth birthday, by which time her surname had become Insley.

Unlike Rudolph Bergstrom, Ernest Thomas Sherry, Jr. managed, with the exception of his affair with the fabulous Baker girls, to stay out of the newspapers, but doubtlessly the embarrassment, while admittedly not nearly as mortifying as that which afflicted Cornell Woolrich—his wife had accused him of being a pallid, wan aesthete incapable of consummating their marriage—was enough to last a lifetime. Ernest II married unsuccessfully once again, in Broward County, Florida in 1939, to a Louise Stanford Hensley, the union lasting less than a year. The third time proved the charm for earnest Ernie, however. He died in Seminole, Florida in 1979 at the age of sixty-eight, his third wife Elsa having predeceased him by eight years.

Ernie’s son from this third marriage, Ernest Thomas Sherry III, who was born in Manhattan in 1942, died just three years ago in Sarasota, Florida at the seventy-seven, unmarried and unattached, leaving no known family member to make the final disposition of his mortal remains. It is surprising that the family of someone as wealthy and successful as Edna Sherry faded so fully in this fashion, but it is in keeping with what seems to have been Edna’s secretive nature. The mystery author remained a mystery woman to the end.

Note: Four Edna Sherry crime novels—Sudden Fear (1948), No Questions Asked (1949), Tears for Jessie Hewitt (1958) and the Defense Does Not Rest! (1959)—have been reprinted by Stark House.

The Criminous Fiction of Edna Solomon Sherry

Guilty? (1923) (play)

Through Different Eyes (1929) (film) (with Milton Herbert Gropper)

Inspector Kennedy/Homicide (1929) (play) (with Milton Herbert Gropper)

Is No One Innocent? (1930) (novel) (with Milton Herbert Gropper)

Sudden Fear (1948) (novel)

No Questions Asked (1949) (novel)

Backfire (1956) (novel)

Tears for Jessie Hewitt (1958) (novel)

The Defense Does Not Rest! (1959) (novel)

The Survival of the Fittest (1960) (novel)

Call the Witness (1961) (novel)

Girl Missing (1962) (novel)

Strictly a Loser (1965) (novel)