Sometimes the crimes for which we’re most harshly judged and punished are the ones that break no laws. And for young women, pushing back against tradition, expected codes of behavior, and the social contract can provoke the severest of reactions.

In my debut novel, The Nobodies, two girls discover they have the ability to swap bodies, a power they use to intervene in each other’s lives—sometimes to disastrous effect–over twenty years of friendship. As they literally step into each other’s worlds, Nina and Jess form judgments about what they find and act upon them, unearthing and divulging secrets, disrupting relationships, and making life-altering changes. Their power, though invisible to others, is like a crime against nature, one that allows them to enter and violate the inner sanctum of someone else’s self.

While writing the novel, I sought out other tales of young women overstepping boundaries, not only committing crimes in the traditional sense, but also transgressing against expectations in other ways, as well. Included among the books that have inspired me are stories of murderous teenagers seeking vengeance, daughters defying their families, pupils betraying mentors, friends betraying each other, and young women turning against themselves. What unifies these works of fiction is that their authors give female characters full personhood, by allowing the darkness within them free reign on the page.

The Power, by Naomi Alderman

Who hasn’t heard the (dubious) claim that if women were in charge, the world would be a more peaceful place? This novel delivers a jolting refutation to that idea in its depiction of a world in which the power is suddenly awakened in nearly every girl to deliver fatal electric shocks through touch. Soon all the familiar scripts are flipped: it is boys, not girls, who must be wary of walking home alone at night; it is women who form rebel groups and violently overthrow governments; it is women who maraud, assault, and silence men. Through these reversals of fortune Alderman suggests that whoever holds the power will be twisted and rendered sadistic by it, whether male or female. A fascinating framing device hints at how far-ranging such upheaval could be.

My Sister, the Serial Killer, by Oyinkan Braithwaite

With a title like that, readers’ expectations will be high for bloody thrills. They’ll get them from the opening pages, when Korede is summoned by her beautiful, charismatic, and possibly sociopathic sister, Ayoola, to help clean up the murder of her boyfriend—her third such crime. Readers will also get a sharply funny take on middle-class life in Lagos, Nigeria, the frustrations of dwelling in the shadow of a more alluring sibling, and the angst of being torn between loyalty to one’s family and one’s own standards of morality. This latter dilemma kicks into high gear when Ayoola catches the eye of a handsome doctor at the hospital where Korede works (and pines after him). Korede must find a way to warn him of the danger he’s in without endangering her sister’s freedom. Along with the grisly details of Ayoola’s attacks are witty insights into what men want from women, and how women wield their sexual power.

Sorority, by Genevieve Sly Crane

“Girls are cruelest to themselves,” the poet Anne Carson wrote. There’s plenty of cruelty in these linked stories about the women of one sorority house, directed both at each other and themselves, particularly after the death of one of their sisters. And each sister has her say about the incident in a series of first-person narratives, presenting a kaleidoscopic and nuanced view that goes well beyond the stereotypes of Greek life. There’s hazing, to be sure, but Crane also takes us inside the inner lives of the sisters, from the house’s founders who warded off marauding men during the Civil War with mysterious rituals, to the present-day members who cope with fractured relationships, clandestine romances, dark compulsions, and all the complexities and dangers of young womanhood.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle, by Shirley Jackson

When we first meet Merricat, the singular protagonist of Jackson’s final novel, she’s making her beleaguered way through a village of people who respond to her with suspicion, mockery, and loathing. And as we follow her home to where she lives with her dutiful, fearful older sister Constance and her enfeebled Uncle Julian, we begin to understand why: these three belong to the wealthy Blackwood family, who live in a grand house perched on the edge of town, and the rest of their former, imperious clan are gone, poisoned at dinner six years prior. Constance was the suspect, as she prepared the meal; despite being exonerated the villagers still see her as a killer. There’s little mystery as to who really diminished this family—the source of intrigue lies instead in how the survivors exist in the crime’s aftermath, and in how Merricat manages to win your allegiance, even as she fantasizes about the gruesome deaths of all outside her castle.

The Vegetarian, by Han Kang

Following nightmares of the violent, bloody deaths of animals, Yeong-hye decides to give up meat. This seemingly simple act unleashes chaos within her family, whose resulting dissolution is revealed in three parts, from three different perspectives. To her husband, Yeong-hye was, prior to her conversion to vegetarianism, “unremarkable in every way”; to her brother-in-law, she has since transformed into something not quite human; to her sister, Yeong-hye is “soaring alone over a boundary she herself could never bring herself to cross.” Yeong-hye, whose vegetarianism begins as a disruption and soon metamorphoses into a graver transgression of social norms, does not speak for herself in this novel; the reader, too, must strive to interpret, as her relatives do, what is happening inside her as her body and behavior undergo alarming changes.

Carrie, by Stephen King

The Brian De Palma film adaption looms large enough that when you think of Stephen King’s first novel, what probably comes to mind is Sissy Spacek’s eerie, bug-eyed glare through a veil of pig’s blood, as she unleashes hell on her bullying classmates. But the novel is worth revisiting for its unusual framing. The story not only brings us inside Carrie’s tortured school and home life, and the development of her telekinetic powers, but also presents a range of perspectives on that climactic prom night, from reporters to scholars to eyewitnesses. This structure suggests that Carrie’s act of vengeance is not merely a matter of cause-and-effect, but a crime that resists explanation. King himself, in his memoir On Writing, reflects that he never quite came to like Carrie White, nor did he trust Sue Snell’s motives in sending Carrie to prom with her boyfriend. Proof that a novel’s characters need not be readers’ friends, or even especially likable, in order to feel compelling and real.

Sula, by Toni Morrison

Like the “plague of doves” that presages her return to her hometown, the title character of Morrison’s second novel is powerful, mysterious, and relentlessly challenging, not least to her best friend, Nel. Despite their differences, the two are deeply enmeshed, at least until their involvement in an accident results in the death of a child and the effective end of their own childhoods. As an adult, Sula pursues an independent life. “I don’t want to make somebody else. I want to make myself,” she says, a crime in and of itself for a Black woman of her time and place. Her freedom includes what looks like a betrayal of Nel, but our notions of which girl is the noble one, which the deceitful are complicated by the book’s ending.

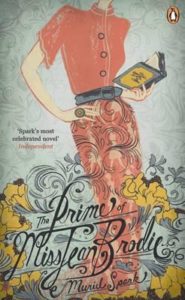

The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, by Muriel Spark

An influential educator with fascist sympathies who tries to manipulate one student into an affair with an older man, and persuades another to join the effort to support Franco in the Spanish Civil War—clearly the criminal here, no? But over 60 years after the publication of this classic short novel, Miss Brodie remains impossible to pin down, as does the star member of her “set” who eventually betrays her. Undoubtedly a singular and independent woman, Miss Brodie casts a long shadow over her favored group of girl pupils, and her impact on their lives is revealed through the book’s frequent and striking use of flash forward, in a way that is devastating and hilarious at once.

***