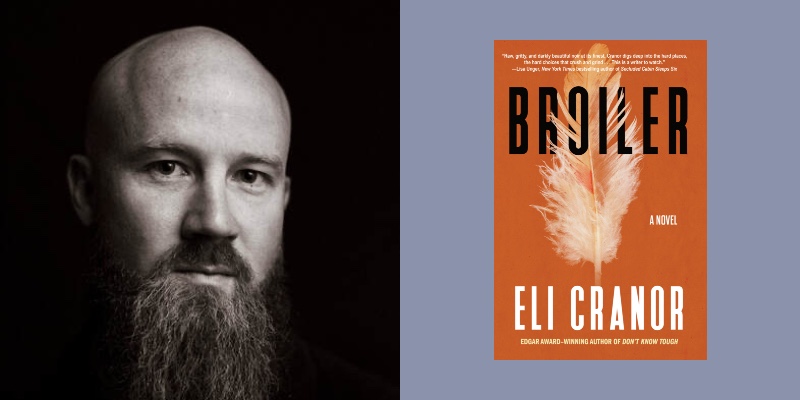

If the reading and writing world(s) of Eli Cranor could be distilled into one word, it would probably be: empathy.

The “beautiful simplicity of a single word”—albeit laden with subtext—is evidenced by the title Broiler (July 2, 2024; Soho Press). The nationally bestselling author and educator’s third novel is ostensibly about the chicken processing industry but really about the American Dream, the pursuit of which can become a nightmare when tainted by ambition and greed. Inevitably, there is a power struggle between those who’ve attained it and those who aspire to.

It’s a story that Cranor—the Edgar Award-winning author of Don’t Know Tough and Ozark Dogs—is uniquely qualified to tell. Having both grown up and taught in Arkansas, he has witnessed firsthand the sacrifice that feeds sustainability. While industry is imperative for economic survival, it’s also a lifeblood built on labor. And it’s often the most hardened hands that are left the emptiest, sometimes seeking to take what was never given.

Now, Cranor reflects on how the dual empathy machines of reading and writing allow us to feel experiences other than our own …

John B. Valeri: There’s this notion in poetry to let a title do heavy lifting. Using Broiler (a deceptively simple title, if ever there was one!) as a touchpoint, introduce us to the story’s layers.

Eli Cranor: I love that you mention poetry in reference to the title. A good friend and mentor of mine, Greg Brownderville, once talked to me about the power of one-word titles. He’d just released a poetry collection called “Gust.” I can’t remember what he said, exactly, but it had something to do with the beautiful simplicity of a single word. It was one of those conversations that simmered forever. Then, when I heard the word “Broiler,” I thought, Damn. That would make a great title for a thriller set around the chicken processing industry.

JBV: The book is dedicated, in part, to your “first-block students who couldn’t stay awake; now I know why.” How did researching this story, and the realities of a labor job, provide insight into the lives of your students – and in what ways has this understanding enhanced your ability to relate to them?

EC: Those students were working night shifts at the local chicken processing plant. I talked to them about their jobs. They told me about the frigid temperatures, the metal-mesh gloves, the dull knives. But it wasn’t until I started to try and write this story that I began to realize all that they were up against. Reading is an empathy machine, but writing takes that experience to a completely different level. Or at least that’s how it worked for me. This book was a stretch. It’s different from my first two novels, and because of that stretch, I learned more from this manuscript than any other.

JBV: To expand on that: Fiction allows us to embody lives other than our own. For instance, in Broiler, you write from the perspective of immigrants, mothers, the privileged, the impoverished. How did you endeavor to capture their experiences with authenticity and nuance – and in what ways can doing so serve as a catalyst for building empathy?

EC: Henry James once said, “A writer is someone on whom nothing is lost.” I’ve always taken that to mean a writer is someone who is always watching, always listening. Which goes back to empathy, right? In order to write authentically, you have to feel for people. You have to have spent time watching and listening. This, of course, doesn’t mean you’ll get everything right. My first two books didn’t have such challenging gaps for me to write across, but there were still things I wrote (mainly about Arkansas) that didn’t ring true for every reader. That’s the deal, I think. You can take a chance, but if you get something wrong be ready to listen, to learn.

JBV: It can be said that this book is about the American Dream, and how our pursuit of it can lead us astray (no matter how noble our intentions). How do aspirations influence your core characters’ (Gabriela, Edwin, Luke & Mimi) actions and motivations? In what ways does the crime genre elevate such a story?

EC: My favorite line in the book comes in the penultimate chapter: “For every American Dream there is a corresponding nightmare.” It took me almost eighty-thousand words to boil the whole novel down to that one sentence. People have said they’ve had trouble eating chicken after reading Broiler. And that’s fine, but that’s not the point. The point is how much is enough? And what is the cost of wanting more?

JBV: You make your home in Arkansas, where your books are set. In what ways do you find that place informs plot – and how does your intimate knowledge of the region strengthen your rendering of it on the page?

EC: I was born and bred in Arkansas, but I’ve lived in other places. South Florida. Sweden. Those years away from the Natural State helped me see my home through new eyes. There’s so much I love about Arkansas—the landscape, the people, the space—but there’s also a lot I’d like to see change. That’s something I’ve started thinking about more the farther I get into my career. What change can my stories bring about? I don’t know the answer to that. No novelist does. My books will impact each reader differently. My only hope is that my words leave a mark.

JBV: Your editor is the great Juliet Grames, who is also a celebrated author in her own right. What is your collaborative process like? Please share a few examples of how her feedback strengthened this particular book.

EC: Juliet is the best. Period. She’s the smartest person I know. She speaks a dozen languages (that’s a guess, but I’m probably not too far off). She’s an editor, an author, a wife, a mom, a daughter, a sister. She brings all of that to every book. She sees things I can’t see, and she never takes a shortcut. She always gives me “The Full Grames Treatment.” Spoiler alert: there is no “Half Grames Treatment.” For Broiler, specifically, we went through about six revisions before we reached a publishable manuscript. A lot of this had to do with the inherent challenges this novel presented, which we’ve already mentioned. I’m very thankful to her and the whole Soho team for giving me the freedom to write this book, for believing that I could do it. The best advice Juliet gave me before I launched off into revisions was, “Meet the challenge with love.”

JBV: You share generously of your writing life, both on CrimeReads and elsewhere. In what ways does reflecting on the craft influence your relationship to it – and what do you believe are the benefits of offering that wisdom to others, whether they’re actively writing, contemplating writing, or simply curious?

EC: I always try to remember how it felt coming up. I was so damn tenacious. I think that was the athletic part of my brain kicking in. I wanted to know how other people wrote books. The word counts. The hours. The tools of the trade. I teach a couple of creative writing courses at Arkansas Tech University now. This experience keeps me fully grounded in the world of young writers. I’m very lucky because the result is a perpetual beginner’s mind. There’s freedom when you’re just starting out. Anything is possible. No idea is too big or too challenging. In the end, though, the only thing that really matters is the work. The process of it. That’s the thing I try to get my students to understand. When in doubt, just write.

JBV: Leave us with a teaser: What comes next?

EC: Through sheer luck—or pure madness—I had drafts of Ozark Dogs and Broiler ready to submit by the time Don’t Know Tough came out. That was in 2022. Since then, I’ve been working on my next novel, Mississippi Blue 42. Long story short, MB42 is a screwball noir set in the big-money world of college football. In terms of style, I leaned heavily on my love of Elmore Leonard. I also think there are elements of Carl Hiaasen in the zany but believable turns of the fanatic plot. Mississippi Blue 42 is scheduled to release in August of 2025, right around the same time the NCAA delivers its first-ever payments to “student athletes.”