I was sixteen when Before Sunrise was released in UK cinemas, the perfect age to watch Ethan Hawke’s Jesse and Julie Delpy’s Céline spend the night together in Vienna, before agreeing in the final scene to meet six months later in the same spot. I was young enough to yearn for such experiences myself, and just about old enough to understand that the characters not meeting again might actually be more romantic than them doing so.

I think I would have happily left the story there, but when I was twenty-six Before Sunset was released, and we learned that Jesse did return to Vienna while Céline did not, instead meeting again in Paris nine years later.

But for me, the most memorable part from the whole trilogy comes in the third film, Before Midnight, which, growing up at the same speed as the characters, I watched at a parent and baby showing, my six month old baby strapped to my chest. In it, Jesse and Céline are now the parents of twin girls as well as Jesse’s teenage son from a previous marriage.

“You know what?” Céline tells Jesse. “The only time I get to think now is when I take a shit at the office. I’m starting to associate thoughts with the smell of shit.”

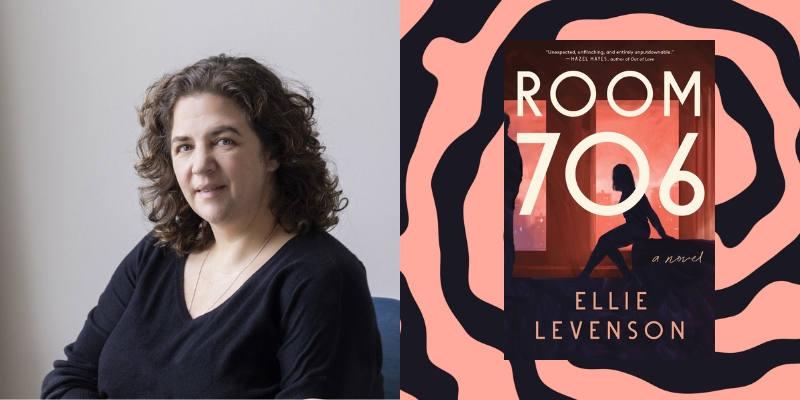

Although I don’t remember thinking about this trilogy while writing Room 706, it’s hard to deny its influence on my work, particularly the will-they-won’t-they ending of the first, and the impact of parenting on a relationship in the third.

However it’s another film that I think may have solidified the lasting impact of an ambiguous ending in my brain. I accidently saw the Dutch original of The Vanishing (Spoorloos) on television as a young teen. I say accidentally, in that had we known how scary it was, I would never have been allowed to watch.

In it, a woman goes missing at a service station, never to be found. Her boyfriend is driven mad by the not knowing, and allows her abductor to take him too, so that he may experience what she experienced, and know what happened. The final scene sees him wake up, buried alive in a coffin.

This scene has haunted me ever since, at times giving me literal nightmares. (In the American remake he is rescued by his new girlfriend, which is a happier ending, though not for the first girlfriend whose grave they also find).

So, I now realize, it is this gap between a happy ending and a sad ending, that interested me when writing my own novel. In Room 706, Kate, a happily married mother of two, meets her lover James in a hotel every few months to have sex. It’s a form of me-time, she reasons, and could just as well be buying a new pair of shoes or having a massage. Except this time, while James showers, she turns on the television and sees that the London hotel in which they are in has been taken over by terrorists. Kate has to grapple with what she should tell her husband about why she is caught up in the news event the whole country is watching unfold.

In Room 706, it is not too big a spoiler to say that, while the book is finished, the ending is somewhat ambiguous. It’s not quite a cliffhanger, a device used to ensure the reader comes back for the next instalment, because I have no intention of writing a sequel. But it does give the reader scope to make their own decision about what happens next.

This isn’t unusual in books. In The Paper Palace by Miranda Cowley Heller, which I read after submitting the near final edit of my own book to my publisher, we see the main character faced with the decision whether to stay with her husband or choose her childhood love. We know that she swims towards one of them, and the author has said subsequently who it is she thinks the main character chooses, but without a sequel we cannot know whether, after the book ends, she completes her swim or not, and whether anyone in fact waits for her on the other side.

For anyone studying the plays of Shakespeare, an often cited rule is that comedies end in marriage (think A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Taming of the Shrew, Twelfth Night) and tragedies begin with them (think Hamlet, Othello, Anthony and Cleopatra). Not only does it help neatly divide and remember the Shakespearian canon, but it allows those of us who have been married some years to lord it over younger readers.

You may have romantic notions now, it seems to say, but just you wait until life has had its way with you. See what happens then. That is, a comedy in part one is likely to be a tragedy were there to be a part two.

This is perhaps an idea that is clearest of all in the end scene of The Graduate, when Duston Hoffman’s Benjamin has run away with Elaine from her own wedding to another man. Their elation turns to terror when, sitting on a bus, Elaine still in her wedding dress, they realise that like everyone else, their future has not been written and could go in any direction. It is up to each member of the audience to decide their own version of the story, and whether they have made the right decision.

Prior to the horror of The Vanishing and the romance of Before Sunrise, I was growing up on a cultural diet that was heavy on Fiddler on the Roof. In the musical, Golde, the wife of Tevye the milkman, has an entire song devoted to her own domestic load. Her husband, confronted with his daughter wanting a love marriage rather than an arranged union, asks his wife whether she loves him.

“For twenty-five years I’ve washed your clothes, Cooked your meals, cleaned your house, Given you children, milked the cow, After twenty-five years, why talk about love right now?” she sings at him in response. It’s starker here, written down, than it is in song, where it is somewhat comedic, and perhaps not really so different to Céline’s experience of motherhood.

Fiddler on the Roof ends with the Jewish residents of Anatevka (in the Russian Empire, modern day Ukraine) leaving their homes due to anti-Jewish pogroms. It is 1905. There is sadness, but there is also hope. And yet we the audience know that for those characters who do not leave mainland Europe, a far worse fate awaits their children in the years to come. Their ending is written by history, even when their existence has not yet been made up.

Perhaps a happier example of the unknown ending should be the Choose Your Own Adventure stories that took off in the 1980s and 1990s, in which children could choose which path the hero took at multiple stages, so that each book could be multiple stories. They remind me now of Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken”: “Yet knowing how way leads on to way, I doubted if I should ever come back.”

Discussing this with a friend recently, she reminded me of The French Lieutenant’s Woman by John Fowles, in which he offers the reader three potential endings to his novel. This was in fact one of the first books that my own book group read, when we formed in the early noughties. To offer three endings may seem daring of the author, when usually we must choose one. But on reflection, three barely seems enough, when there are so many more possibilities that could happen after the last page has been finished.

Of course, as the author, I have my own ideas about what might happen to my characters after the last page. In fact Kate hints at them when she is imagining a future in which she survives and grows old with her husband, Vic.

But my characters have also discussed the idea of the multiverse—the possibility of every permutation of the world existing in parallel. To me, the readers are the multiverse—no book has a final ending, not even fairytales that end “happily ever after,” because every reader could, and should, have their own version of what happens next in their head.

Ends

***