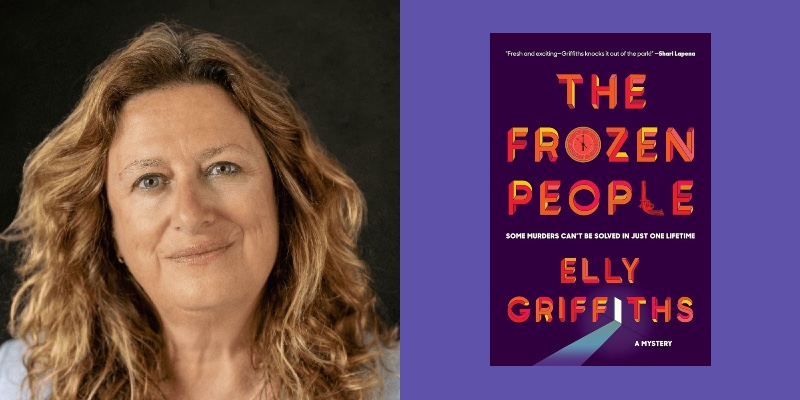

Elly Griffiths is the author of more than two dozen mystery novels, including The Great Deceiver, The Last Word, and the short story collection The Man in Black. She remains perhaps best known for the Ruth Galloway series where over fifteen books the forensic archeologist solved a number of crimes, and for the Brighton mystery series about a stage magician set in 1950s and 60s.

Her new novel The Frozen People is the beginning of a new series. The main character Ali Dawson is an unusual kind of detective who was recruited to join a unit where she gets sent into the past. A government minister, who happens to be her son’s boss, makes a request for her to be sent to 1850 to look into an ancestor. Things go awry as cases in the past and present dovetail. The book is less interested in the how of time travel than it is in looking at the Victorian era and these characters and their relationship to the present. Plotting such a mystery is a complex task, as Griffiths detailed, but she’s always been a writer focused on character and atmosphere, and the scenes in both the present and past offer her the chance to demonstrate how she’s so good at crafting both. We spoke recently about the magpie-like nature of writers, plotting, and the comforting escape of a time travel book.

You mentioned in the book’s afterword that the idea for the story came to you in a flash and you plotted this out one day with your husband in a pub.

In a way, the idea for The Frozen People has been in my head for a really long time. It was really just ‘time-traveling detective’. I just had it in my head for a long, long time. But it wasn’t until this day, which I mentioned in the back of the book. Andy and I had been to see some Neolithic flint mines, which doesn’t sound very romantic and wonderful, but Andy’s an archaeologist. I’ve been invited to lots of lovely places. Should we go to New York? No. Should we go to San Diego? No. Should we go down a mine? Yeah, I’d love to do that. [laughs] So we went down this Neolithic flood mine and it was amazing because they’re made with a flint axe or an antler.

Andy, as I said, is an archaeologist, but he had worked as a curator at a museum. He was saying about how museums have these odd little collections that are often not on show. Partly because the provenance is really dodgy. It’s often these British Victorian archaeologists. 19th century amateur archaeologists wandering around, picking up stuff that they fancied. Brighton Museum, where he was working, had this odd Egyptology collection. That was, funny enough, collected by a man called Griffiths. That conversation made me see a way in which I could take my time-traveling detective and take her to the 19th century to investigate one of these strange little collections. And a rather sinister group of people called The Collectors.

It’s interesting that that was your way in. The people who assembled these collections had this strange magpie-like nature, which I think writers have to have also.

I think that’s really true. Writers are the same, really. We take things from all over the place. I’ve got a notebook, as so many writers have. With this book, I had the idea of a time-traveling detective, then I had the collectors, and then I had the character of Ali. I think I needed those three things, really, to make the book.

I think everyone who’s read Ruth will love Ali. She’s such a great character, which is probably not surprising for people who have read you.

I so hope so. And I do hope that people who like Ruth will like Ali. Ali has had this background. She’s been married several times. She’s been a single mother. She has one grown-up son who she adores, but with whom she disagrees politically. I hope she’s a character people enjoy being with. She also has a rather irreverent attitude to things. And I hope is sometimes quite funny.

You’re also clearly fascinated with the Victorian era, which you get into in depth in the book.

I’ve always been fascinated by the Victorians. You hope other people are as fascinated as you. Years and years ago, when I was at university, I did a Master’s in Victorian Fiction. I became really fascinated by that mid-Victorian period, when all their certainties have been shaken. There was this book called Life of Christ, which said– I don’t think very controversially now, but was controversial then– that the Gospels weren’t contemporary accounts of Christ’s life. They were written afterwards. Then you’ve got Darwin’s Origin of Species, telling them they’re not descended from the angels, they’re descended from apes. Then you get the Communist Manifesto about the same time. I think they all were just a bit sort of shaken and wondering what to believe. This is the world that I wanted to take Ali to. And great clothes as well. I really enjoyed that.

Ali is this very irreverent, unconventional character in the present. You send her back to the 19th century, where of course, it would be easy for her to fit in and blend in. [laughs]

[laughs] Yes, I did want her to be a kind of very modern woman in lots of ways and attitudes, but also in her appearance. Because as you wander around streets, you see people who would be very at home in Victorian times. There’s a certain look that would be at home. But Ali, I gave her bright that sort of fire engine red hair. She’s got a nose ring. She’s very modern. I wanted to have somebody like that where it would be a big shock. She has to dye her hair back to her original brown, to take out the nose ring, to put on all these uncomfortable clothes. I did enjoy writing about the 19th century from a very modern viewpoint.

You treat time travel as something that happened, we did it. Let’s not get bogged down in these details.

A reviewer said that I was “elegantly vague,” which I thought was very nice of them. I liked the elegant, I have to say. I didn’t really want to go into too much detail. I wanted to give just enough to imply that somebody understood it, even if it wasn’t me. There’s a brilliant Italian physicist called Serafina Pellegrini, known as Jones, who has perfected this technique. I kept thinking of, I don’t know if you got it in the States, a TV series called Life on Mars. It’s about this modern day detective who goes back to the 1970s. And I don’t think they ever really explained why. I think they did at the end, but I honestly don’t remember the explanation. What do I remember about that series? I remember the characters. I kept thinking, I hope my readers will remember the characters and not the not the specifics of how you time travel. When you start the book, they’ve already time traveled, it’s already given, they know how to do it. They accept it, so I just hoped the readers accept it.

Because it’s not really about the how they travel. It’s about these two periods. It’s about these things that connect us and tie together and sort of how each period thinks about the other.

That’s a really interesting way to look at it. I think it’s not so much about the time travel, but about things that link us. It raises questions because there’s a murder in the in the present day– in our day– and a murder in the past, and and how they’re linked. Also about how women are treated in today’s world and how they were treated in 1850. I think there are lots of links. As I said before, it’s a human story. It’s about Ali and her son and the people she meets. And her team. I quite like writing about a tight knit team. I enjoyed that in the Ruth books. I enjoyed I enjoyed writing about their team and how they coped. I’m not trying not to do spoilers, but Ali gets stuck there. So then what happens?

We could just say, “things go awry.”

Things go awry. That’s a very good way of putting it. Things don’t quite go to plan.

When you first came up with the idea and the shape of it, did you originally think, this is going to be a series, and how it would work?

I did hope it would be a series. When I started the Ruth books, I think I had a two book deal at the very beginning. I knew there would be a long story there, but I wasn’t sure that I would get to write it, because it’s a privilege to get to write a series. Eventually there were fifteen Ruth books. So with this, I hadn’t really thought about how many there would be, but I did hope there’d be a series just because there’s so much scope. I wrote this first book hoping there’d be a series and I’ve just finished writing Book Two called The Killing Time. So there is at least two. I think there will be at least four to start with. That’s how far I’ve thought ahead.

I don’t want to say that things aren’t concluded, because the murder is solved, but there are dangling elements.

The central murder is tied up. I don’t like it when an author doesn’t tell you who did it and why. But you’re absolutely right, there are certain plot lines left open. In Book Two, Ali goes back to 1851 and picks up some of her life there. While also investigating a case that’s linked to mesmerist, which was another really interesting Victorian obsession.

There’s a way in which this is an odd book, because science fiction readers might go, there’s not enough science fiction, and mystery readers might go, oh, there’s science fiction. How do you balance that? How do you say, look, there’s something for everyone to read and enjoy?

I think you have to go back to what we were saying about character. If you like the characters, you’ll go on this journey with them and try not to think too much about whether it’s a science fiction or a mystery. In a sense, it is an old fashioned mystery story. There’s a crime committed. There’s nothing supernatural about why or how it’s committed. I just hope that people will you’d go along for the ride because they like the characters. I’m sure you’ve noticed that crime fiction has been doing this quite a bit recently. Gillian McAllister’s Wrong Place Wrong Time. Stuart Turton’s The Seven Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle. I think those books are so readable because the characters are so good. In a way, we’re asked to believe odd things in any crime novel, aren’t we? I mean, we’re asked to believe that one detective solves a really complicated crime every year. To be honest, there are not many archaeologists who solve as many murders as Ruth.

People always joke, we live in a science fiction world now.

We really do. And if you’re writing a novel looking at AI, or some of the things that are happening, the change is happening so quickly, I would doubt that you could keep up with those changes. Maybe we just need to escape into a time travel book. [laughs]

I wanted to ask about plotting a book like this. Beyond the research, which is a lot more in depth. This feels like a much more complicated book to plot.

It was really hard, because I’m not a great plotter. You know the old thing about being a plotter or pantser. I’m probably in the middle, in that I plot a little bit. Less as I’ve gone on, actually. I’m sort of quite happy to start a book where I don’t know quite what happens.

I’ve actually always found timelines quite hard to follow ordinarily. A timeline that involves going back in time to 1850 was quite hard to follow and quite hard to track. When I realized that it actually wouldn’t be the same day of the week in 1850, I almost gave up my will to live. [laughs] My editors Jane in the UK and Jeremy in the US were having to be very helpful about what happened when and where. It was a challenge plotting things. And of course, the huge challenge right out there straight away is if you write a time travel crime novel, and somebody goes back in time to solve a crime and they solve it, well then it never happened, which does make your head want to explode. So I had to avoid that happening. There are many, many traps there for the time travel author. But when it does fit into place, it feels very neat, which is lovely. There were a few moments like that that were very good fun.

That’s interesting that you like to figure out the story as you write because having read your books, I would say that they’re deliberately and carefully structured, but not tightly plotted.

I think that’s a good way of looking at it. I quite like to have many possibilities as I go through the books. I quite enjoy doing misdirection. I quite like to have many options, and then at the end to tie it all up. One of the things that my editor Jane often says to me is, slow down a bit, we need to explain this a little. I really do enjoy books that have clever plots though. Sometimes as a writer you think to yourself, I’ve found the greatest plot twist, but then you realize Agatha Christie’s already done it. [laughs] So in some ways there’s nothing new, but I do like a plot point that maybe twists on a name or something very simple that could just be not quite how you’re seeing it.

Christie famously would write to the end, figure out who the murderer was in the process of writing it, and then go back and throw in red herrings and make that character seem least likely to be the killer.

I was quite shocked when I found that out! I think it was when I read her diaries. She’s an absolute master of plotting. And atmosphere, I think. It’s very interesting that that’s what she did. Sometimes I think that does work, because if you know from the beginning who did it, you risk either making them too sinister, but I think more likely making them too nice. So I think sometimes if you don’t quite know yourself as a writer, you can surprise yourself, which is quite fun.

I know sometimes people say they don’t change very much in the editing process, but really, it is key. I think particularly with a crime novel, because you do have to go back to the beginning and tighten it up a bit. Maybe put in some early clues to that person that you’ve just decided did it.

Talk a little about writing London, because so many of your books have been set elsewhere but you really seemed to enjoy writing about the city.

I was born in London. I went to King’s College London, and I lived there for ten years, so it’s probably the place I know best, apart from Brighton. I love writing about it. It is those layers of history that are so fascinating. I remember going on one of those walking tours of London, and we’re looking at this old wall, and the guide pointed at this layer of charred bricks. She said, that’s the Boudiccan destruction layer. In Roman times, Queen Boudica, from the Assini tribe, she came into Londinium, as it was then, and basically burnt it down. And you can still see where that happened. I love that. The east end of London, which is where Ali lives and works, is really interesting because you can see Roman remains there, lots from the plague years, and then you’ve got Victorian London. It was really interesting to think of the shape of London. Ali lives and works there in, in 2023 in this book, and then she goes back to 1850, and there were some bits she recognized and then some bits she doesn’t. It’s a kind of palimpsest, layers and layers of things. I suppose that’s any big city in a way, but London’s the one I know best.

It’s a great city. A wonderful, diverse, liberal, nice place to live. It has its problems, like any city has. Both my grown-up children live in London, and they really love the life there. It’s a really interesting place to write about. I hope I’ve shown some of my affection for it as well. I think sometimes it’s tempting to write about a city as if it’s like Gotham City or some very dark place, but actually, there are really lovely and forgotten bits. The University in the book, Queen Mary’s, where my daughter went, is a real example of that. Suddenly, in the East End of London, there’s this beautiful university, with a canal going through it, and this really strange, old graveyard in the middle of this modern university.

So much crime fiction will take that darker view, and you’re writing about two different periods, and going, neither are perfect, it’s changed, but lots of things remain the same.

Exactly! The thing about Ali’s London– in present day and in the past– is that it’s her friends, the people she meets there, that make it bearable. She has good friends in the present day, and to her surprise, she does kind of make friends, even though she’s desperate to escape, in Victorian times. I quite enjoyed writing about that.

You clearly had a lot of fun writing the Victorian scenes. I mean, it may have been agony, but on at least some level, you seemed to really enjoy that.

I really enjoyed it. As I say, it’s one of my favorite periods to read about. I love Victorian fiction. I love artists’ London. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and those sort of movements. I loved writing about all the strange, rather dissolute artists who live in this house. So yes, it might have driven me really mad, trying to add up when they were born, and when they died, and to work out how old they were at any given time– but I did really enjoy writing about that.

So you finished the second book, you said, with more to come.

That’ll be out in the UK in February next year, and probably the US, I imagine in June or July next year. With more to come. And more to come in the other series as well, so.

I like having different characters in your head at different times. There’ll be at least one more Brighton mystery. I might go back to Ruth one day. I’m just giving them a bit of a break. Ruth and Nelson need some peace, need some privacy. I might well go back to them one day. I’m just waiting for their daughter to grow up.

With a child, characters can’t have as many hijinks and adventures.

So true. One of the interesting things– but also problems if you decide to let your characters age in real time, which I did– is that fifteen years on, their lives are very different. I think you maybe have to approach it in a different way. But I loved writing the Ruth books. I loved pulling all the loose ends together in Book 15, but equally it was really fun, and a bit scary, but also very exciting to start a new series. And to meet a new team. That was one of the things I learned from the Ruth books. I really love writing about a team. I really enjoyed writing the people in The Frozen People who are a slightly ill-assorted, but basically affectionate team.