‘The play’s the thing,’ says Hamlet, ‘wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king.’ Hamlet famously stages a play called The Mousetrap, showing a fratricide, hoping that it will tweak his murderous uncle’s conscience. Later, watching an actor perform, he says,

What would he do

Had he the motive and the cue for passion

That I have?

It’s all there: conscience, motive, murder, passion. The old joke describes Hamlet as a play full of quotations but perhaps it’s more accurate to say that it’s full of book titles, specifically murder mysteries. Murder Most Foul, A Killing Kindness, No Wind of Blame, The Cue for Passion. Macbeth is not far behind. In The Postscript Murders, I invented a crime series with Shakespeare quotations as titles. I was able to use some of my favourites, which my publisher always unaccountably rejects, such as The Sleeping and the Dead, Thank Heaven Fasting and The Prince of Darkness is a Gentlemen.

And then, of course, there’s The Mousetrap. Agatha Christie named her play, which has just resumed performances in London after a run of 68 years broken only by Covid, after Hamlet’s conscience-tweaking production. Christie loved Shakespearean titles. By the Pricking of my Thumbs. Taken at the Flood. Sad Cypress. Although it should be noted that her original title for The Mousetrap was Three Blind Mice.

Why is there such a link between crime fiction and the stage? Why are so many mysteries set in the theatrical world? Even the language of the theatre is the language of murder. Bad acts die on stage. Actors who laugh in the wrong place are said to have corpsed. Good acts make a killing, they’re a hit, they smash it. Theatrical backers are angels and the highest (and cheapest) seats are known as The Gods. It’s no wonder that so many writers have had someone fall to their death on stage.

British author Simon Brett writes a much-loved crime series featuring actor Charles Paris. I asked Simon why he chose a theatrical setting for the books. He replied that, for him, the play really was the thing. ‘Each production is a new environment, with a new cast of characters, each bringing his or her ambitions and anxieties to the mix.’ For me, this gets to the heart of the matter. A theatre is a mini-world, each production a mini-life. And, in a cast, you often have a microcosm of society: young and old, rich and poor, leading ladies and voiceless extras.

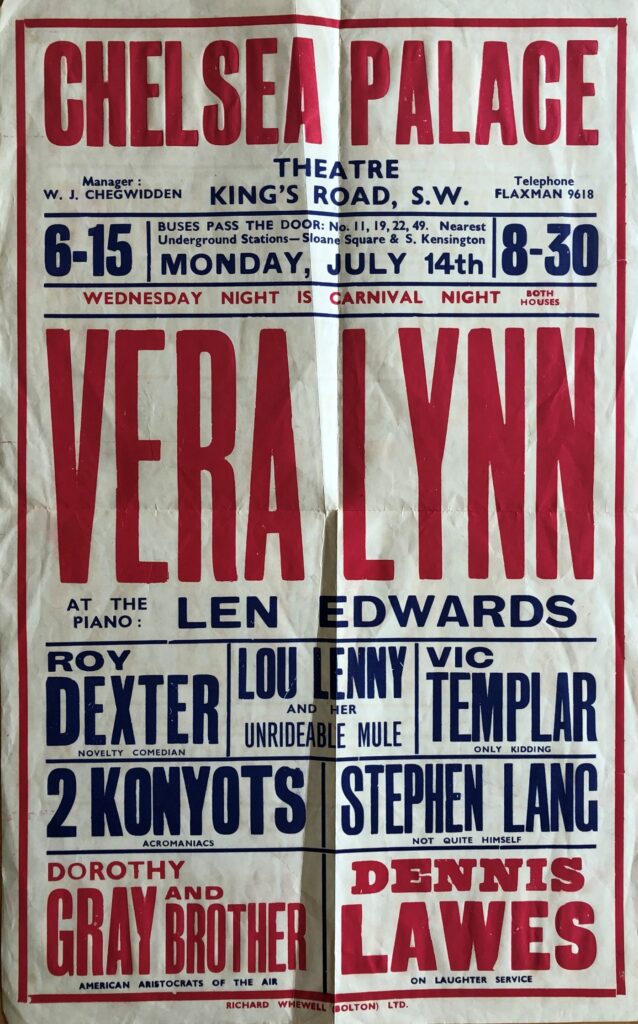

I have to declare an interest here. My grandfather, Dennis Lawes, was an actor and his life as a touring Vaudeville entertainer is the basis for my Brighton mysteries. Grandad was on a different playbill every week, moving from town to town, staying in dubious digs. The peripatetic nature of actors makes them ideal sleuths – or villains. This is particularly true if you set your action in the past. Rory Clements writes an excellent historical series about John Shakespeare, William’s fictional actor brother. William was an actor too, of course, and one of the parts we know he played was the ghost in Hamlet. Charles Paris gets this part too in A Decent Interval. Shakespeare knew all about acting. I love Hamlet’s injunction to the clowns to ‘speak no more than is set down for them.’ Obviously Will Kemp and co got sick of Shakespeare’s frankly terrible jokes and started adding gags of their own.

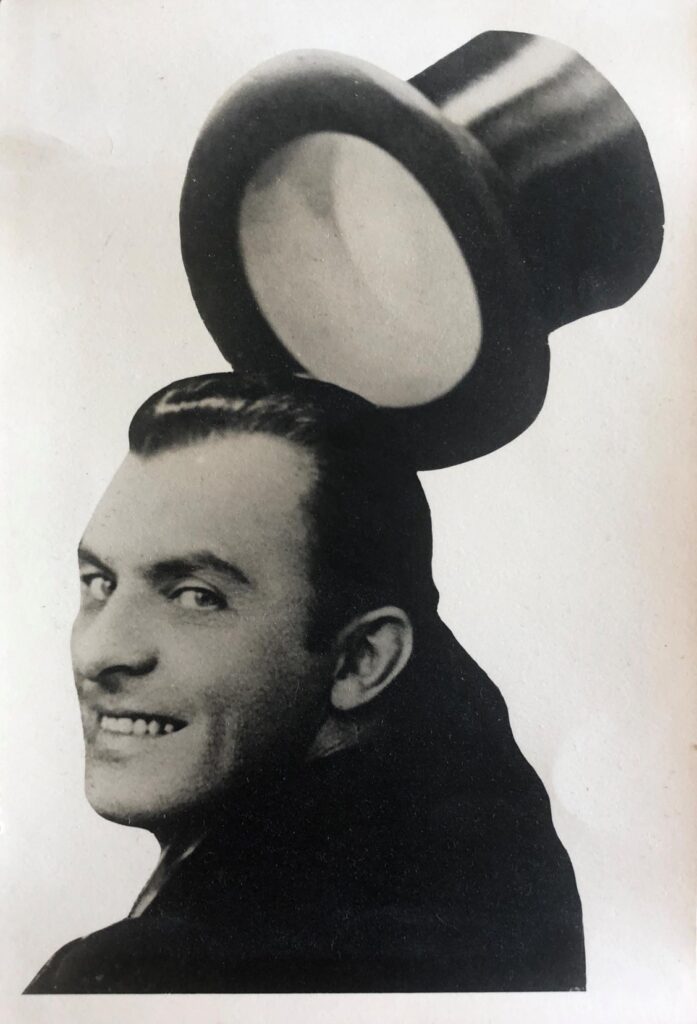

Actor Dennis Lawes and playbill, provided by Elly Griffiths

Actors are mobile, both geographically and socially. My grandfather made my mother have elocution lessons at school, not because her accent was ‘lower class’ but because he worried it was too posh. He wanted her to be classless and socially neutral, able to play any part. Theatricals are experts at deceit and, so the theory goes, good at spotting it in others. On a side note, actors also make pretty good crime writers; for example, Mark Billingham, Robert Daws and Hugh Fraser (who plays Hastings opposite David Suchet’s Poirot).

My grandfather was a comedian and also played both the Dame and the Demon King in pantomime. There is something inherently sinister about this peculiarly British form of Christmas entertainment. The villain always enters stage left which, apparently, goes back to the days of medieval mystery plays where the right of the rudimentary stage represented heaven and the left, hell. Pantomime has its origins in Italian commedia dell’arte and left in Italian is ‘sinistra’. It’s no surprise, then, that crime writers were quick to grasp its murderous possibilities. Nancy Spain, famous in the 1940s and 50s and now thankfully back in print, wrote a splendid novel called Cinderella Goes to the Morgue. Simon Brett follows in the tradition with The Cinderella Killer.

One of my favourite theatrical mysteries is Opening Night by Ngaio Marsh. Almost all the action takes place in the Vulcan Theatre. The cast – as they are always described – frequently gather on the stage, including for the final ‘summing up’ by Inspector Alleyn. When Alleyn appears, very late in the story, Marsh says that he ‘made his appearance up-stage and centre.’ The Vulcan is a leading character and is even, due to faulty gas pipes, briefly a suspect in the murder. Before the titular opening night, Marsh describes the silent auditorium, the ‘dead lamps’, the empty seats staring at the curtain. Everything bided its time in the dark theatre. It’s the perfect locked room scenario.

This is a very spooky description and theatres are famously haunted places. Perhaps because they are so full of tears, laughter and passion – so full of words – it’s impossible to imagine them ever being completely empty. Many theatres have a ‘ghost light’ which burns day and night to keep the spectres company. The Theatre Royal Drury Lane is haunted by the ghosts of Joseph Grimaldi, the famous clown, and Dan Leno, the celebrated pantomime Dame. Grimaldi appears as a disembodied head or sits quietly in the stalls, a sign that the show is due for a long run. Leno’s spirit makes itself known with the scent of lavender perfume which, less pleasantly, the actor wore to mask the smell of urine.

Actors make great sleuths and theatres good settings. But I think it goes deeper than that. Reading crime fiction is an active experience and, as in every theatrical performance, the audience makes a difference. Grandad used to say that Mondays were always difficult because the landladies were given free tickets and, allegedly, it takes a lot to make a theatrical landlady laugh. A book needs an author and a reader just as a play needs actors and an audience.

As Shakespeare says in As You Like It:

All the world’s a stage

And all the men and women merely players

They have their exits and their entrances

And one man in his time plays many parts.

Article continues after advertisement

There are definitely a few titles in there.

***