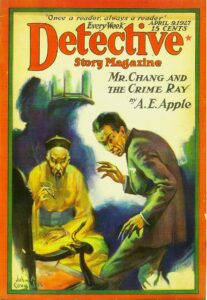

In the waning weeks of the dreary Depression year of 1931, twenty-eight-year-old Yee Gow Suen of the little Mississippi Delta town of Dermott, Arkansas (Pop. 2942 in the 1930 census), an avid young reader of American pulp crime fiction, was moved to compose a letter to Street & Smith’s Detective Story Magazine, one of the premier pulp publishers between the wars. In his missive the Chinese immigrant politely but forcefully registered his complaints about the popular Mr. Chang series of stories by A. E. Apple, a mainstay contributor during the Roaring Twenties to Detective Story Magazine [DSM hereon]. The magazine quickly published Yee Gow Suen’s words in its January 2, 1932 issue. The letter follows below in full:

Dear Editor: There is not any doubt in my mind that Mr. Apple is a great writer. But his imagination is too broad with the facts. The things he describes in his hop-joint [i.e., opium den] story are not true, because no such things exist in this country.

Why does Mr. Apple always place a Chinese in a villain role, with a desire to trap an American girl? Such stories have a tendency to create a bad impression of the Chinese people. His Rafferty stories are clean and great.

Your other authors are grand. Tell them to keep up the good work. Hope you will forward a copy of this letter to Mr. Apple, and also print it in the chat. I am

“A Chinese Who Knows”

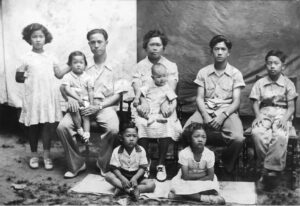

American success story Ye Gow Suen and his family in Dermott, Arkansas, c. 1941

American success story Ye Gow Suen and his family in Dermott, Arkansas, c. 1941

The DSM editor did indeed forward a copy of this letter from “A Chinese Who Knows” to Mr. Apple, and the pulp writer’s reply appeared right below it in the same issue. Apple sought to reassure Mr. Suen of his good intentions by urging that he in fact knew many Chinese people and that he deemed the Chinese “the most honest of races.” The writer noted that he had introduced into his Chang tales the character of Doctor Ling, a Chinese detective whom “honest Chinese merchants” had employed to pursue and “eliminate Mr. Chang as a blot on their race.” The villainous Mr. Chang, Apple avowed—surely somewhat ingenuously, given the noxious history of “Yellow Peril” crime fiction in the United States and United Kingdom during the early twentieth century—merely “happened to be Chinese; no matter what other race he might have been, there would have been objections from that race.”

In fairness to Apple, one gets the impression from his stories that Mr. Chang’s “Chineseness” is rather random; with Chang, Apple seems more like he is indicting a single malign individual rather than, as with Sax Rohmer, an entire civilization or race, this at least in part because Chang, who in contrast with Dr. Fu Manchu, has no grand ambition other than enriching himself, is not a very convincing “Chinaman.” Here, for example, is a sampling of his speech: “Stick around, old boy! In a few minutes we are going to open a can of sardines and make merry.” Not exactly the slitting image, as it were, of the devil doctor, is it, old boy?

Elmer Albert Apple (the initials of the first two names were transposed in his pseudonym) was born in 1891 in the city of Findlay in northern Ohio, about forty miles south of Toledo, and died in 1963 at the age of seventy-one. After a stint as a shipping clerk in his German-American father’s oil well supply company, Apple adventurously struck out on his own in his twenties to write newspaper and pulp magazine fiction. In 1917, not long before American entry into World War One, Apple departed the United States for the Canadian province of Ontario, where two years later he wed Toronto native Beatrice Nixon. Although in 1920 the husband and wife, both of whom were practitioners of Christian Science, were living on the southern shore of Lake Erie in the city of Lakewood, Ohio, they soon returned to Ontario, where Beatrice gave birth to their two sons, Barnabas (“Barney”) and David. From his pulp magazine fiction Apple, who typed the stuff in a small wooden shed he wryly referred to as “the prison,” earned around 3000 Canadian dollars in 1930, or about $36,000 American dollars today. Beatrice supplemented her hard-working penny-a-worder husband’s income by laboring as a waitress. Presumably he contributed to the care of the couple’s two young boys while his wife was out slinging hash.

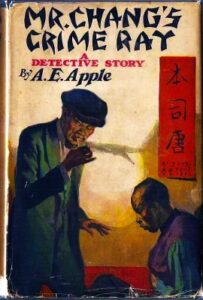

The prolific pulpist published the first of his thirty-three Mr. Chang tales in DSM on September 9, 1919, just a day before his marriage in Toronto to Beatrice. Additionally, the author published a pair of Mr. Chang novels in 1925 and 1928. The Chang crime saga ran for almost a dozen years until May 23, 1931, the same year in which Yee Gow Suen sent his letter to DSM. In June of that year the Canadian census recorded the Apple family residing on holiday at Parry Sound, Ontario. Elmer reported not having done any professional work since December 1930. In his 1931 reply to Yee Gow Suen, he mentions having suffered from a “long illness.” In fact, Apple stopped writing entirely in 1932, publishing only two nonseries tales in April and July of that year, and the next year Beatrice placed him in a mental institution, Hawthornden State Hospital (originally known unsubtly as the Northern Ohio Lunatic Asylum), in Sagamore Hills, located halfway between Cleveland and Akron.

Publicly a columnist declared in 1935 that Elmer Apple had “suicided” in 1933, but in truth the author lived on for another three decades. (Perhaps in 1933 he had attempted to kill himself.) Apple is listed as a patient at Hawthornden in both the 1940 and 1950 U.S. censuses, but whether he remained there until 1963 when he died is unclear. A 2012 post at The Irreverent Psychologist blog notes that during the Twenties and Thirties patient overcrowding ran rampant at the underfunded Hawthornden and that horrifically after World War Two a belated investigation of conditions at the facility found patients had been beaten dead with such objects as “belts, key rings and metal plated shoes.” Certainly this grim setting was amply worthy of any pulp crime fiction writer’s fevered imagination, but sadly in Apple’s case it appears all too likely that there was no miraculous reprieve on the final page, no last-minute storybook ending.

Ruins of Hawthornden State Hospital, an attraction to ghost hunters today

Ruins of Hawthornden State Hospital, an attraction to ghost hunters today

The Mr. Chang series receives no less than four full pages of coverage in Bill Pronzini’s Gun in Cheek, his classic tongue-in-cheek 1982 survey of bad crime fiction (so-called “alternative classics”). Unaware that Mr. Chang’s highly imaginative creator himself wound up institutionalized for two decades or more as a patient in a booby hatch, Pronzini writes that the Mr. Chang stories overflow with “hilarious logic….insane coincidences, incredible situations, a crazy quilt of plot devices, Abbott and Costello characters, and a cathode-ray device ‘resembling a three-circuit nonregenerative radio’ that is capable of killing people at thirty feet, can be strapped on the back and used portably as long as the wearer carries a very long electrical cord with him, and is known among other appellations as the Crime Ray, the Death Ray and the Murder Machine.” Weirdly presaging his own imminent confinement, in one of the late Mr. Chang stories from 1930, the Asian supervillain is captured and exhibited in an iron cage all over China, where he is hated as well, as a prelude to his public beheading. Chang ultimately escapes this terrible fate of course, because you can never keep a bad criminal mastermind down for very long.

The nineteen stories in Elmer Apple’s Rafferty series, which Yee Gow Suen in contrast with the Chang tales enthusiastically praised as “clean and great,” are about a Raffles-style super thief. Or really, one would have to say, a super-duper stupendous thief. These were published between October 1, 1927 and November 1, 1930. Notes Robert Sampson in volume three of his book series Yesterday’s Faces: A Study of Series Characters in the Early Pulp Magazines, Rafferty in the stories deigns to amuse himself by modestly purloining “large items” such as “houses and trains, and museums and towns.” The final solo installment of the Rafferty saga I swear to you is entitled Rafferty Steals 200 Dicks. How could a person top that? In 1931 Apple came up with the brilliant stroke of pitting Rafferty and Chang against each other in a couple of late super-rogue mashup tales. Recalling House of Frankenstein, he might have called the result House of Chang. All he needed was a wolfman.

It may seem absurd to us today that A. E. Apple was ever an in-demand pulp writer, that many a reader eagerly punked down their fifteen cents (twenty cents in Canada) at their local drugstore expressly to read an A. E. Apple story about fiendish Mr. Chang or roguish super crook Rafferty. British crime fiction critic Julian Symons hit upon a certain truth when he pronounced in his genre survey Bloody Murder that comparatively few American pulp fiction writers “had more than the elementary writing skill of describing violent action with some conviction.” Many of them, sadly, had not even that. As Bill Pronzini points out in Gun in Cheek, such writers “lacked the commitment” of someone of a pulp titan like Sax Rohmer, who like a great showman genuinely loved writing his hokum. These imitators “didn’t believe—or if they did, not deeply enough—in their characters and their story lines,” Pronzini notes. “They also lacked Rohmer’s imagination, his sense of place and space, and his ability to portray ‘Satan incarnate’ in a convincing fashion. The best of these imitators produced pallid reproductions of Fu Manchu. The worst of them produced hilarity.” Or, if you happened to be a loyal, pulps-loving Chinese-American like Yee Gow Suen, a certain sense of confused hurt.

Today Dermott, Arkansas, for over six decades the adopted home of Yee Gow Suen, is a declining town of around 2000 people—down from its peak of close to 5000 in 1990—located about a three hours’ drive from the city of Memphis, Tennessee. In the 2020 census all of ten Asians were recorded living there. Yee Gow Suen, a Chinese-American who loved American pulp crime fiction (though clearly not its more egregious racist aspects), was born in China in 1903 and died in 1991 in Dermott, where he and his wife, Mary Chiang Suen, owned and operated a Chinese grocery and takeout restaurant. In the Nineties Dermott was one of the Mississippi delta towns which still had a Chinese grocery. I would love to believe that at this Dermott grocery, or perhaps the local drugstore, paperback crime fiction was still featured for sale on revolving book racks too.

***

Back in 1982 in his book Gun in Cheek in a chapter with a title too indelicate for me actually to give here (I shall simply call it Chapter Seven), Bill Pronzini wrote about the advent of the “wicked Chinaman” archetype in American and British crime fiction. “The evil Oriental villain, as typified by Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu, was a favorite of a small but prolific group of mystery and thriller writers who flourished between the two world wars,” Pronzini observed. “So much was written during that period of fiendish devil doctors and ‘yellow hordes’ bent on world domination, of secret passages and underground lairs, of fearful opium dens and exotic Chinese tortures, that a folkloric belief in these things became widespread—and is still believed in some quarters today. Yet nearly all of it is spurious sensationalism, concocted out of ignorance and racist attitudes of the first half of [the twentieth] century.”

Dashiell Hammett, a Twenties pulpist who was, it should go without saying, an inestimably superior writer to poor, demented Elmer Apple, was able in his crime fiction actually to write about Asians in a far more measured manner. “Yellow Peril” tropes are still present in his work, but they are handled with some semblance of nuance compared to a hack like Apple. Scholar J. K. Van Dover has argued that when it came to the portrayal of Asians in his fictions Hammett “however cleverly or clumsily” played with racial cliches rather than “naively accepting or malignantly employing them” and in so doing helped, in however small a way, to expand his “readership’s cultural horizons”—or, at least, that is what Van Dover believes that Hammett believed he was doing. There are, to be sure, a lot of caveats here, but within those limitations Van Dover makes a positive statement about Hammett’s crime writing in regard to its portrayal of Asian characters. Is it also an accurate statement? I believe so.

We see Hammett’s most wholesale subversion of the “Yellow Peril” trope in a Continental Op short story entitled called “Creeping Siamese,” which first appeared in Black Mask in 1926. In “Creeping Siamese” a man staggers into the office of Continental Detective Agency in San Francisco and promptly collapses, dead. He was stabbed in the chest and he used a red sarong to stanch the fatal wound. From this detail Detective Sergeant O’Gar of the police department Homicide Detail suspects that “brown men” or “Hindus” may have been responsible for the crime. Later a couple seems to connect the murder victim, Moonstone like, to some “brown-skinned” creeping Siamese who were attempting to retrieve a cache of stolen gems from the murder victim. The Op remains skeptical of this theory throughout the story and soon enough he completely demolishes it. While the real culprits are being led out to the police car, O’Gar and the Op notice a trio of jolly, inebriated Malay sailors passing down the street. The Op imagines what a jury whose imagination had been fired by lurid tales of “creeping Siamese” might have done to these innocent men. Innocent non-white men were still being lynched in Twenties America, to say nothing of being wrongly imprisoned.

Hammett’s more hard-boiled fans sometimes express aesthetic distaste for “Creeping Siamese,” finding the tale too cerebral and ratiocinative (which is precisely the reason why puzzle master Ellery Queen loved it). The Paperback Warrior complained at his blog in 2022 that “[Creeping Siamese] could just [as] easily [have] been an Agatha Christie Miss Marple mystery story. The Op is normally a resourceful badass, but in this one, he was more Sherlockian.” This is true enough (and hardly a terrible thing in my view), but happily in “Creeping Siamese” we still get some of our resourceful badass’ patented snark like “Being around movies all the time has poisoned his idea of what sounds plausible” and “Is it your idea that whoever did the carving advertised himself by running around in the streets in a red petticoat?”

Most significantly, however, these Op wisecracks, and indeed the entire thrust of the story, serve to discredit the “Yellow Peril”—or in this case “Brown Peril”—Asian villain trope, so beloved in crime tales from Victorian author Wilkie Collins’ The Moonstone (1868) up to the pulp era’s Fu Manchu saga and even the 1955 children’s animated Disney film Lady and the Tramp (“We are Siamese if you do please/We are Siamese if you don’t please.”) Observes the Library of America website on this matter: “What makes [the race fiction] potent is how groundless stereotypes and racist fears guide not only white law enforcement officials but also the public—or as the Op crossly puts it, ‘God knows what a jury would make of it.’” This is as acute an observation today as it was a century ago.

Especially so, one imagines, if that jury had made a habit of reading an Apple—an A. E. Apple Mr. Chang tale, that is—every day. Or, if not every day, every month in Detective Story Magazine. Yee Gow Suen most definitely was on to something when he wrote the pulp magazine from Demott, Arkansas way back in 1931.