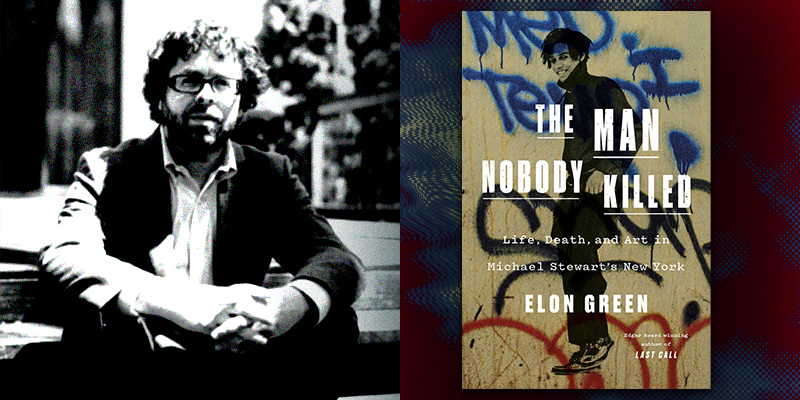

Elon Green’s first book, Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York, won the Mystery Writers’ of American Best Fact Crime Award. The book brings together a deeply researched police investigation into the serial killings of gay men in Manhattan in the early 1990s, with a deep concern for the lives of the men killed and their families. The book was later turned into a four-part documentary for HBO. As a journalist, Green’s writing about crime is marked by an acutely felt empathy for the victims, exemplifying the new true crime genre with its focus on the stories of victims and the larger social injustices surrounding them.

His newest book, The Man Nobody Killed: Life, Death, and Art in Michael Stewart’s New York, details a forgotten case of police brutality in 1983, which, though shocking at the time, feels familiar today. I recently spoke to Green about the book, and his work of researching and writing about crime.

James Polchin: Who was Michael Stewart?

Elon Green: Michael Stewart was a young black man, twenty-five-years old. He lived with his parents in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. Like a lot of people his age in the early 1980s in New York, he was getting by with sort of a hodgepodge of jobs. He was incredibly handsome, so he was doing modeling. He had an incredible interest in music, so he was doing djing. He worked at the Pyramid Club [in the East Village] and he appeared in Madonna’s first music video. He was surrounded by some of the great artists of the era, and he had his own interests in the art world. In fact, he and Jean-Michel Basquiat were dating the same woman on and off. But it’s always hard to say who a twenty-five-year-old is, because at that age you’re still mostly promise, and you’re still mostly unformed. But he was someone who had done a lot of interesting things and surrounded himself with a lot of fascinating people. He had a lot of promise.

JP: So what happened to Michael after midnight September 15th, 1983.

EG: Michael is hanging out among other places at the Pyramid Club. He calls up a woman that he had hung out with one other time before named Patricia. She meets him at the club and they have a really nice time together. Not terribly romantic, but they’re getting along pretty well. And then it gets to be pretty late, so they head out, and they’re walking around the Village a bit. Michael decides he has to go home. They share a cab uptown and Patricia leaves him at the 14th Street and 1st Avenue subway, the L. Or, as it was called back then, the LL. She kisses him. They say they’ll keep in touch. And she watches him go down the subway steps.

EG: Michael is hanging out among other places at the Pyramid Club. He calls up a woman that he had hung out with one other time before named Patricia. She meets him at the club and they have a really nice time together. Not terribly romantic, but they’re getting along pretty well. And then it gets to be pretty late, so they head out, and they’re walking around the Village a bit. Michael decides he has to go home. They share a cab uptown and Patricia leaves him at the 14th Street and 1st Avenue subway, the L. Or, as it was called back then, the LL. She kisses him. They say they’ll keep in touch. And she watches him go down the subway steps.

A fairly short time after that, a transit police officer who has just gotten on shift allegedly sees Michael deface the wall of the subway and puts him under arrest. A series of events leads him to be transported to Union Square, which is where the District 4 precinct was located. Before he has a chance to be booked, he was on the ground near Union Square, surrounded by, eventually, eleven officers, and in full view of more than 30 freshmen at Parsons School of Design, whose dorm was on the west side of Union Square. Michael was beaten into a coma. Subsequently, thirteen days later, he dies at Bellevue Hospital.

JP: One of the compelling parts of the book is this mystery of what actually caused that coma, and what then caused the subsequent death. You give a really detailed accounting of the eyewitnesses, many of whom you interviewed for the book. Some of the former Parsons students and other folks who were around Union Square that night who also witnessed part of what happened.

EG: There was the subway toll clerk who saw them go upstairs. There was an auxiliary police officer named Robert Rodriguez, who was working at a sandwich shop by the 1st Avenue subway. He saw Michael being taken up the stairs, and then among the other non-student witnesses there was an academic named Annemarie Crocetti who was on the 11th floor of a building, and she also was a witness.

JP: In the book you focus on Michael’s body and what it could tell the doctors and the investigators about what happened to him, and what it couldn’t tell them.

EG: Because of the thirteen days of being in a coma, what would have been unambiguous signs of certain types of trauma were made even more ambiguous. And it made it almost impossible, eventually, to determine the cause of death because, of course, they couldn’t do an autopsy until he was dead. That meant that there were wounds that were healing up. There were bruises that would disappear. And it meant that, by the time he died, his body was not accurately representing the trauma he had endured.

JP: One figure who stands out in this story is Dr. Elliot Gross, the medical examiner, who at the time was thought to have covered up evidence in the case.

EG: He had been the chief medical examiner in New York City for a couple of years. In that capacity, he was essentially the last word on any kind of death that was suspicious. There were many, many autopsies in New York per year, and generally he would not handle them personally. But sometimes he would. When John Lennon was shot in 1980, he would do that autopsy, or when Tennessee Williams died in February of 1983, he was overseeing that autopsy. And so, you know, if there was a high-profile death in New York City there was a good chance that Gross would have some involvement. This was not, in my opinion, a matter of ego. This was, for him, a matter of accountability. If something is going to be in the spotlight, then he felt he should be the one to shoulder that burden.

Going into the book, I took it for granted that what had been reported about Gross, and assumed about him, was true. Which is to say, that he had engineered a cover-up on behalf of the police and that he had disposed of evidence. But it was really interesting to find that, not only was that not true, but that Gross had actually been fairly conscientious about taking steps to do the opposite, to go out of his way to preserve evidence and to document it, exhaustively. Which is not to say that he didn’t make mistakes or exhibit poor judgment. I think he did. They were honest, understandable errors.

JP: And as you point out, he wasn’t that good as a communicator, but that’s all they had. Gross had to go out there and make the statements and engage with the press.

EG: There are two aspects to being a chief medical examiner. There’s the science, the medical side of it. But there’s also the communications side of it. The medical examiner’s office didn’t have a communications department. I don’t know if this is still true, but it was back then. There was no junior person designated to talk to the press. Elliot Gross was it. And so, if there was a press conference that needed to happen, he was the one pushed out there in time for the six o’clock news.

I don’t think he particularly liked the press. He didn’t enjoy it. And that meant that he wasn’t very smooth. So he turned out to be a far more interesting character than I ever would have expected. To my knowledge, I’m the only journalist he has talked to since retirement. It took some effort to get him to talk. It was an utterly fascinating experience to talk to him and find out that he didn’t even really want to be a doctor. His initial ambition was to be a journalist.

JP: There’s also a story here about the East Village and the downtown art and music scene of the early 1980s. Stewart had ambitions to be an artist, and he was both part of that scene, but was also on the fringe of it, yes?

EG: I wouldn’t so much say fringe, because I feel like that has a certain connotation. But I would say he was on the periphery of it, trying to work himself towards the center. He was someone who really wanted in and had designs to do so.

JP: As you capture so well in the book, many of these artists where on the verge of becoming well known. We are talking about artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, David Wojnarowicz, and Madonna among others who were just about to become big.

EG: To an almost ridiculous degree, frankly, because it really is that last moment before they explode. When Madonna makes that video with Michael, she’s still big in New York. But when Michael is beaten and then dies, her first album, I believe, has already come out.

JP: What drew you to this story?

EG: So that’s a question that’s hard to answer, because the answer is different, depending on when in the project I’m thinking about it. Initially looking at the Wikipedia entry, which is how I found it, the case just seemed almost preposterously interesting, whether you know Basquiat and Haring and Madonna. I just assumed there would have been a book about this case, but in fact there had never been. I think the thing that really solidified it for me was when I began talking to the witnesses and I realized how unambiguous this all was. Sometimes there’s no gray area. I also just found Michael to be a really interesting person, and I found a lot of complexity to someone who is only twenty-five. I found the people he surrounded himself with were utterly fascinating and lovely. The whole story to me was just so compelling. And a lot of it was very much unprecedented. The East Village was not prepared for something like this. The community had never dealt so closely with an issue of police brutality.

JP: But they found ways to respond, as you detail in the book. They rallied and they protested. You relate how David Wojnarowicz made fliers for the first Union Square rally in support of Stewart while he was still in the hospital. They organized quite quickly.

EG: Particularly thanks to Hauoi Montaug, famous doorman who worked at the dance clubs Palladium and Studio 54 and Danceteria. In another lifetime, he would have been a union organizer.

JP: How they came together to create some public attention for this case, one of the first high-profile police killings in the country, is a fascinating part of the book. It also struck me that this organizing anticipated the kinds of protests around the AIDS crisis that this community would engage in the coming years.

EG: The case came at an extraordinary moment in the city’s history. One of the reasons why so many people remembered Michael’s funeral was that, in their minds, it was the last time they went to one that wasn’t for someone who had died of AIDS. That neighborhood was on the precipice, and they didn’t know it.

JP: In that light, there’s also a larger political context for Stewart’s killing—those early years of Reagan’s America. Can you talk about how that played a role in this case?

EG: Although the problems in the city begin pre-Reagan, they basically typified Reagan’s project, which is to defund public goods. What we’re seeing today is like a speedrun of something Reagan could only have dreamed of. But New York in 1983 was recovering from its near-bankruptcy fiscal crisis of the 1970s, where everything was underfunded, the city was falling apart at basically every level down to the parks and the subways. They were not even hiring cops. I mean, that was one of the things that I read that utterly blew my mind—the city being so underfunded that they were actually not hiring cops. And to me everything that I write about in the book is downstream of that fiscal situation in the city. One of the tragedies of the Stewart case, and there are many, is that I think it was inevitable, if not for Michael, then for somebody else. You’re talking about transit police that were underfunded, had terrible equipment, and patrolled solo, which made the job terrifying. And then they often have a chip on their shoulder because they weren’t given the respect of the city cops. And, of course, the training was also poor. So violence was just an everyday part of the job.

JP: And accountability of the transit cops. That was also an issue here in terms of how they were held accountable for what happened to Stewart.

EG: Internal affairs refused to investigate for reasons that I’ve never gotten to the bottom of—the man who could have answered that question died. Later on, the New York County district attorney would actually do a fairly thorough job, and then later, the MTA would also do a great job with a commission. But yes, legally, the accountability was poor.

JP: I want to talk a little about craft here because we don’t tend to talk about craft when we talk about these nonfiction crime books. You interviewed many of the eyewitnesses including some of those former Parsons students, along with a raft of other research. What is the process for you of going from all this research to story?

EG: It’s so easy, because the research is the story. The interviews I got from the witnesses, for example, are nothing but story, nothing but visceral tales. They were just telling me incredible things. That was not a difficult transition. Unlike with Last Call, the narrative in this book was fairly clear to me from the beginning. I knew what details I wanted, and it was mostly just a question of where to find them, and who to talk to. Whether it was getting commission reports from the municipal archives on Chambers Street, or some obscure file at the New York Public Library, or some file that one of my sources just kept in his attic, I knew the stuff was there. It was figuring out where it would be. That was a challenge, and maybe the greatest challenge, I faced writing the book.

Also, when I’m writing—and nobody believes me on this—but I don’t think about the reader at all.

JP: Who are you thinking about?

EG: I’m thinking about the people I’m writing about. In the case of Last Call, and to some extent with The Man Nobody Killed, I’m thinking about the loved ones, the victims. I’m absolutely not thinking about the reader. You just do what’s best for the story.

JP: One of the earliest things I read from you was an article you wrote about race and true crime stories. You describe how the genre of the true crime is predominantly about white victims, written by white writers, and read by white audiences. And at the end of that piece, you write that true crime “should expand to the point where it’s unrecognizable.” What did you mean?

EG: It’s funny that you mention it because The Man Nobody Killed is, I hope, an example of that. I don’t think it’s getting classified as true crime. It doesn’t have the classic tropes that even Last Call had, which is to say, a procedural and the hunt for the perpetrator. But if The Man Nobody Killed is looked at through a certain lens, it is nothing but crime. There are examples of police beating black New Yorkers pretty much throughout the book.

JP: Right. You write about Eleanor Bumpurs who suffered mental health issues and was killed in her apartment by the police. Her death amplified the protests over Stewart’s killing. You also write about the infamous Bernhard Goetz vigilante subway shooting of four Bronx youths, all happening within those early years of the 1980s.

EG: I think that the book is as much true crime as anything else. And I hope it’s an example of what I had wanted when I wrote the essay years ago. I’m not optimistic about the genre. And it hasn’t changed to the degree I hoped that it would. But I’m trying to do my own little part.

JP: One last question, and it has to do with New York in the 1980s. Last Call took place in the early 1990s but had echoes of the 1980s. Is there something about that era that compels you, that interests you in the research?

EG: I was born in the late seventies. I went to the city with my parents and my grandparents, and I still have memories of that New York. It was always interesting to find out more about stuff that I always had hazy recollections of, like the Goetz case and Bumpurs killing. My grandparents subscribed to Newsday and the tabloids were all over those stories. Though it isn’t so much that the era compelled me, because, as with Last Call, it wasn’t that the early nineties compelled me, either. It’s always about the people. It doesn’t really matter to me when a story takes place. I have to care about the people, because I have a very hard time doing a lot of reporting about someone I don’t care for.

_______

James Polchin is an Edgar Award nominated writer, professor, and cultural historian. He is the author of Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall, and Shadow Men: A Tangled Story of Murder, Media and Privilege that Scandalized Jazz Age America.

Elon Green is the author of The Man Nobody Killed and Last Call, and was a producer of the HBO documentary series based on the latter book.