You could forgive the New York Times for mistaking Nothing Serious for a “rom-com.” It opens, after all, with a classic rom-com premise: Peter, Edie’s long-time bestie and secret crush, has broken up with his girlfriend, and it seems like he might finally realize that his soulmate has been right in front of him the whole time. But, alas—he quickly starts dating Anaya, a feminist scholar whom Edie can’t help but admire. When the brilliant, beautiful Anaya is found dead, Smith’s canny debut twists from possible rom-com into something darker—a propulsive mystery, a tech industry satire, and an earnest examination of how gender and money shape our fates.

Set in San Francisco in 2017, the novel holds up a funhouse mirror to the culture of girlbossery and “unicorn” start-ups that once seemed to promise utopian living. At 35, Edie is aging out. She is consumed by online dating, corporate ladder climbing, and egg freezing. What emerges in the friction is a one-of-a-kind coming age story wrapped in the trappings of a thriller.

Smith’s genre-bending novel is informed by her own experiences as both a tech industry founder and a dating app survivor. We sat down to discuss everything from fertility treatments to Tana French, as well as Emily’s journey from pragmatist to artist.

KB: So you and I met in a nonfiction workshop almost a decade ago now. I remember the essay you were working on was about tech and dating. I’ve been wondering: was that the germ of this book? Were you trying to write about your lived experiences and then it grew into Nothing Serious? Or were they always sort of two separate projects?

ES: I’ve always written about my own experiences—tech, relationships, dating, self- discovery and identity. And I was writing a lot of essays before I had the idea forNothing Serious. I had also written another book that was very autobiographical, more “literary” you could say, without the mystery element. Between the personal essays and that novel, I was writing very much based on my own life. And so a lot of that work, including that essay I workshopped with you, ended up in Nothing Serious because the book is so much about the hilarity and misery of online dating. Some essays actually ended up word-for-word in Nothing Serious because the excerpts from Anaya’s work are pulled from my actual essays. My tendency in writing is to just pull from my life. I’m not a researcher. What interests me is the real stuff.

KB: Oh, that’s so interesting. I was wondering about Anaya’s scholarship because I found it so clever and organic the way that this more essayistic, philosophical mode gets incorporated into the book. It would feel really preachy to have that kind of voice in fiction, but you were able to introduce it through this epistolary device.

ES: I’m glad that worked, because I was actually very nervous. My agent or editors pushed me to include more of Anaya’s text in the actual work. Edie’s response to that text is so extreme—it’s very life-changing for her—so there was a lot of pressure on the text to be good.

KB: There’s another clever maneuver you do, with a romcom setup in the beginning. You have these longtime friends–Edie and Peter–who feel like they should be together. Peter breaks up with his girlfriend. All of a sudden there’s an opening, but wait—he starts dating Anaya. The next logical step is Edie hates Anaya and tries to sabotage her, a la My Best Friend’s Wedding. Instead you swerve and she becomes infatuated with Anaya—more so than she is with Peter. Was that always the way you envisioned it? That the female bond would kind of overtake the romantic?

ES: The thing I had been interested in exploring, which is very much from my life, is the shift from obsessing over men romantically to obsessing over women platonically. That’s something that I experienced in my thirties. Throughout my twenties, I was surrounded by men in the tech world, chasing men I thought I was inspired by, and didn’t open my eyes to feminism—except in a very “girlboss” way, wanting to beat men at their own games and be in charge. And then in my thirties, I started to meet women and read books by women, which I never had really done, because I didn’t prioritize women’s art. And my world cracked open. Women became this enormous focus for me, and men just got smaller and smaller.

KB: I feel like all the women I know go through some version of that, where you almost can’t recognize your earlier self. I am always saying to my husband, if you die, I’m done. I find your kind so unimpressive.

ES: I’m literally publishing a substack tomorrow: Is the Misery of Heterosexual Dating Worth Heterosexual Partnership? And I think the answer is no, for women. If my partner and I were to break up, I wouldn’t actually go back to the apps. I know how bad it is out there.

KB: I was thinking about Nothing Serious in the context of these time-of-life books that have been in the zeitgeist. Most notably Miranda July’s blockbuster. It feels like we’re in the middle of a boom of menopausal literature. And this book felt similarly specific to a different time of life. For instance, there’s not a ton of egg freezing in most of the literature I read, even though that’s something a lot of my thirtysomething friends are doing.

ES: I very specifically wanted to make the main character 35, largely because there’s a lot of urgency around fertility at that age. Granted, I have friends who have had kids well into their forties, but at 35 the pressure becomes notably more intense. And I’m just continuously astounded by how little the question of whether or not to have children is represented in books and media. I was completely obsessed with Sheila Heti’s Motherhood, which I think is a Bible for this question; she explores it so well and so deeply. I wanted to set my main character in this period of life where she always assumed she’d have kids and be married, but then she’s well into adulthood and couldn’t be further away from any of that. It forces her to ask the question: do I actually want this? Especially after meeting Anaya, Edie recognizes she feels bad for not having a partner or children like all her colleagues, but finally takes the jump of asking herself if she even wants them. I’ve always wanted to write a coming of age story for a woman in her thirties. I didn’t have a lot of self-discovery in college or in my twenties. I was climbing the ladder, wanting to achieve typical milestones of success. And it wasn’t until my thirties that I lifted my head up and thought, what do I actually want?

KB: At thirty-five, you can actually get labeled by doctors as geriatric. (Now they call it “advanced maternal age,” but same thing.) And yet in your mid-thirties, you can also feel very young and clueless. So there’s this tension–I guess I’m supposed to feel like a grownup now, but I don’t.

ES: When I was in my early 30s, it felt like the end of the first chunk of adulthood. I felt a lot of pressure to be married or whatever. And then you enter your mid-30s and realize: I’m just getting started.

KB: The tech industry moves so fast and the publishing industry moves so slowly that the book almost feels like historical fiction. It’s capturing this very specific, very identifiable era that we all lived through that is almost unrecognizable from where we are now with technology.

ES: The book is set in early 2017, which is right after the Trump election, but before MeToo, which hit in the summer of 2017. So there’s a lot of angst and anger in the air, but not a lot of overt female empowerment. It’s a dark time. Pre-Airbnb’s IPO, pre Uber IPO. Tech money is still flowing in San Francisco but people are just starting to wake up to how bad tech can actually be. Post-election, there was a shift, the tech giants met with Trump in Dec 2016 and people started to realize it was getting out of control. I wanted to capture the privilege of tech bros at that time. The ethos of Zuckerberg’s “move fast and break things,” which is so cringe and awful, but that mentality got you money, VCs loved it. It was a very specific period in time.

KB: That moment when the industry is on the precipice of curdling into something darker mirrors the trajectory of Edie’s life, too. It’s like she was living in this tech utopia with perfect, unattainable Peter, thinking she’ll be young forever, and then she wakes up one day and all of a sudden everything sours, everything turns slightly uncanny. Nothing Serious is definitely not a conventional thriller, which I love. Did you conceive of the book as a thriller or did that come later?

ES: I definitely thought of it as a mystery. The challenge I gave myself after my first book went nowhere was to write a book with a murder in it. I started reading a lot of books in the vein of what I wanted to write. A lot of Tana French in particular–everything about detectives in this book I learned from Tana French. I wrote the first draft very quickly in 2019, but then stepped away from the book while I was running my dating app. Three years later, after shutting down my dating app, I came back to it. The distance was a huge help. When I was revising in 2022, I started reading Patricia Highsmith and Daphne de Maurier, who are so excellent at mixing creepiness and death with a literary sensibility.

KB: Can you talk a little about the dating app that you worked on during those three years and how that work influenced the book?

ES: I got venture capital funding for a dating app called Chorus. The idea was that friends swipe for friends. It was very community-based, and our target audience was 30 and above, which is pretty rare for dating apps (most focus on ages 18-25). A lot of our matchmakers were people in relationships who wanted to support their friends on the apps–specifically we had a lot of married friends helping their single friends. It was a way to kind of loop everyone in and make dating more fun. We grew the community to 10,000 people. I wanted to build a tech company that was values-based and had a heart, but sadly I saw firsthand how impossible that is. It comes down to paying Meta hundreds of thousands of dollars in ads and getting free labor. It was depressing. Eventually, we ran out of money, and I did not want to go back and raise more, so I folded the company. RIP. How it informs the book: it really is hard for women to be dating in their thirties. We had so many amazing women on Chorus looking for relationships, and we had to do so many promotions to get single men on the platform who were looking for something serious. I saw my own struggle validated in our numbers, essentially.

KB: That kind of ties into the title of the book. Was that always the title or did that come towards the end?

ES: The original draft that I wrote in 2019 was called Crazy Single. When I came back to the manuscript three years later, with that distanced relationship, I could much more clearly work with it as a piece of art, not just an outlet for my own personal rage. During that revision process I realized it should be calledNothing Serious. Looking at the book with more humor and distance, the name came clearly.

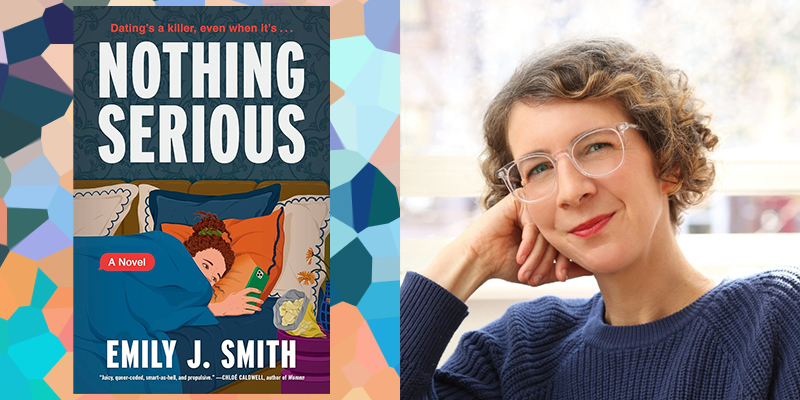

KB: Let’s talk about the cover. It features a woman lying in bed, scrolling on her phone. And I was thinking how it’s funny that on some level this passive image of a person lying in bed–alone, in the fetal position, on her phone–is both representative of modern dating and amateur detective work. How did you imagine the book would look when you were writing it?

ES: When I first got the cover, I thought it was a little too rom-comy. It’s illustrated. It didn’t feel suspenseful enough. But what’s funny is the other option they gave me was super dark. Crazy looking. And I printed them both out and pasted them on books around my house and left them around. And I found that I related to the image so much. I loved that she had curly hair, that the flowers in the picture are wilted. And I thought with the right colors we might add suspense. I look at the book now and I love it. But I’m still worried people are going to think that it’s a romance book. The New York Times called it a rom-com, but it’s super dark.

KB: It is fun though. It’s not a downer.

ES: It’s meant to be kind of funny and playful. There is this satirical component of it. I had a freakout to my agent after we decided on the cover, and just the other day, I had a freakout about the audio book.

KB: Did you listen to a big chunk of it?

ES: I couldn’t. It just wasn’t how I pictured the read.

KB: I listened to maybe one paragraph of Rabbit Hole and then I had to turn it off. It was like listening to my own voice. The narrators were doing a great job, but I just found it unbearable hearing my own words read back to me.

ES: That’s actually great to know. I had visions of me driving on long car rides listening to my book like a psycho. Now, I’m like, I’m never listening to that.

KB: I wanted to talk about money, because money is such a big part of the book at a macro-level in the tech world, but also in Edie’s life. There’s financial tension in the situation with Edie’s mom. She really needs the money. And Peter has a lot of it, which gives him a certain amount of power. How do you approach money in books? Is that part of the characterization early on? It functions here to drive a lot of the plot. It’s relevant to egg freezing and the question of whether or not Edie can leave her job. Certain choices are not totally viable because of money.

ES: I studied engineering, because I grew up poor and I knew I needed to support myself. My parents had no savings, and I figured someone had to. I think a lot of people make decisions about their job based on money. I love seeing money in writing, but it’s not always as common as you’d hope because the choice to be a writer requires a certain amount of financial safety. A lot of writers are poor in the sense that they don’t have money in the bank because writers are paid nothing, but more often than not they didn’t grow up with extreme financial scarcity. Our generation (millennials) can be very judgmental, because I think we’ve been raised to “do what we love” and we forget that some people are working a tech job because they have no other option, or they’ve been poor their whole life. It’s not a game they’re playing; they need to send money to their family. The people I most relate to are my immigrant friends who also grew up with that pressure to support their parents. It creates that delayed coming of age we talked about earlier, with Edie. Until you feel financially stable, you can’t ask yourself, “what do I want to do and read and be interested in?” I didn’t read fiction until I was 29, because it felt like a waste of time. Those considerations were really important to me for the character of Edie, because they explain a lot of why she is the way she is.