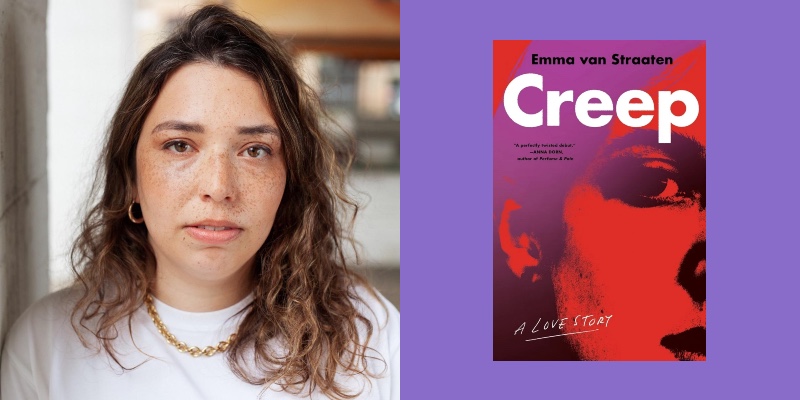

In my debut novel, Creep, the protagonist, Alice, ruminates on the significance of three: “Third time’s a charm, I am told: there are always triples in stories of old: bears, billy goats, blind mice, benevolent fairies – three acts.” It’s appropriate, perhaps that, at thirty-five, I have had three surnames, each for roughly a third of my life. Each iteration of my name has been tightly bound up in my identity as a mixed race woman, which, in turn, is explored in my novel.

I was born to a Mauritian father and English mother as Emma Bundhoo* (to preserve privacy I have changed my birth surname to another common in Mauritius), and, after their divorce when I was one, endured a childhood of mispronunciations and misspellings. Why is your name funny, playmates would ask, and sometimes, after a long look: why are you brown? to which I, bewildered, had no response. I remember emulating the tired way my mother would spell it down the phone: B, U, N for November, D, H, double O. How I wished I was called Emma Lennox, like Mary in The Secret Garden. My mother met our wonderful stepfather when I was six, and thenceforth we grew up in an overwhelmingly white, English environment, and had an entirely typical (privileged) middle class upbringing: ballet lessons and girl scouts, holidays to Spain, going to the cinema, riding bikes, playing board games and reading books. We had English accents, English turns of phrase, English mannerisms, living in our English house, by the English coast – but the fact remained, we were brown, with white parents. Nothing could change this otherness.

My older sister bore the brunt of it. She looked much more like our Mauritian father, with expressive brown eyes, shiny dark brown hair, and skin which tanned readily. I was a more diluted version, watered down: my hair, eyes and skin were all lighter, meaning, I could pass, if not as white, but as western. I had the uneasy privilege of being assumed to be Spanish, Greek or Italian when in holidaying in those countries, of being asked sometimes: so where are you from? in a way that was curious, not aggressive. My sister, on the other hand, was called racial slurs at school.

By the time I was thirteen, she had successfully petitioned our mother to legally change our surnames to her English maiden name: Grimwood. I would never have thought of it myself, but I eagerly, gratefully, followed. It made sense: we didn’t see much of our father, had no links with Mauritius, and, for me, in a childish way, I was keen to not have to explain my name, or feel the familiar rush of embarrassment that it set me apart. Although Grimwood, too, was occasionally misspelt, it was unequivocally and reassuringly English. A layer of otherness was removed, and I leaned into this new name. Before long my schoolfriends had forgotten Bundhoo. I forgot Bundhoo. In making new friends at university, I became merely Emma Grimwood: Grimmy, Grimmers (some still call me this) and it was a thrill to be so assimilated, to pass unnoticed, to ignore my own Asianness even as I struggled to tame some of my body’s revolts against whiteness: seemingly excessive, fast-growing body hair and tendency to store fat on my stomach and thighs, arms that darkened so dramatically in summer that it drew comments. There’s a scene in Creep where Alice remembers an internship where she was asked to make a cup of tea the colour of her skin. That happened.

*

I married my husband in 2017, and, despite it becoming increasingly uncommon to take one’s husband’s name, I wanted to do it, to shift once more. I had been English Emma, and was ready for a more nuanced identity, one where I could cautiously find a middle ground: almost comically European, and delightfully vague, meaning “from the street/road”. It wasn’t a momentous erasure of selfhood as it felt to some friends, but a development of identity, into that of a family unit, whose name our children would have. This, strangely, is where I stopped wilfully identifying as white, and began cautiously, willingly trying on my mixed-racedness, my dual heritage. It is no coincidence that I started writing the manuscript that would become Creep a few years later. As I created the character of Alice, my writing began to make explicit things I had only ever internalised: feelings of self-disgust that came with a 90s upbringing and emphasis on thinness and whiteness, together with the quiet assumption that no one would want me. One of the first changes my editors suggested I make was to tone down Alice’s oppressive self-hatred, to use her vitriolic words about herself more sparingly. It was shocking to realise that there wasn’t one thing I had written in her unhappy, spiteful voice that I hadn’t thought about myself, and deleting them one by one felt cathartic.

Now, my daughters – a quarter Mauritian, a quarter Dutch, half English – are van Straatens and Grimwoods and Bundhoos. One has hazel eyes, one has blue; one’s veins at the crook of her arm are green like mine, the other’s blue like her father’s. I hope they feel rooted in each name, and not at pains to push any part of themselves away. In Creep, Alice never reconciles herself with her racial identity; sees it as something conspiring to alienate her from the life she wants. I, on the other hand, after many years of shame, or trying to ignore it, am at long last, proud to identify as other: as mixed race.