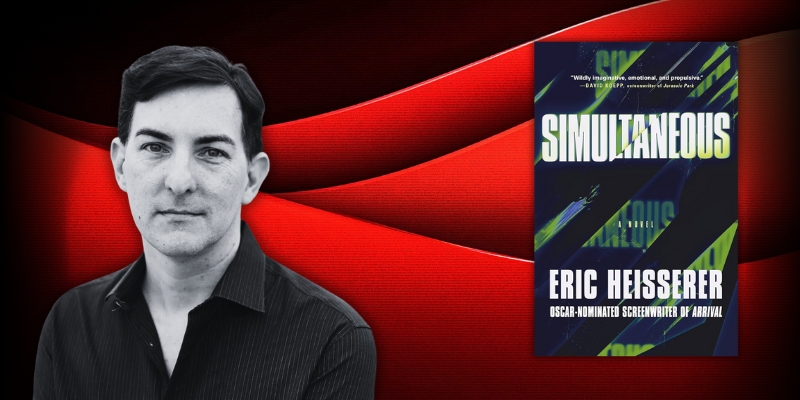

Eric Heisserer is the screenwriter behind many films including Arrival, for which he was nominated for an Academy Award, Bird Box, and The Hours, which he also directed. He also adapted and was the show runner of the series Shadow and Bone. His debut novel is Simultaneous.

The novel features a Homeland Security agent who specializes in Predictive Analytics who comes into contact with a therapist who specializes in past-life hypnosis. One patient leads them into a case that stretches through time, multiple people, a serial killer on death row, a copycat killer, and much more.

I spoke with Heisserer recently about the novel’s influences, his screenwriting philosophy, and his fascination with reincarnation.

*

Alex Dueben: To start with the obvious question, why did you decide to write a novel versus writing a screenplay or TV script?

Eric Heisserer: Well, the novel wasn’t my first swing. When you develop a set of muscles in something, that’s the first answer you have for any new idea. I tried this particular idea out as a screenplay first. Then I thought maybe it worked instead as a series.

I started tinkering with it as a pilot. I came to the conclusion that I just didn’t have the elbow room to fully explore and express this idea in that space. I wound up feeling like I needed to really have my audience on for the full ride so they understood where it was going. Because there’s a lot to digest in it. There’s some pretty big swings there.

My conclusion was, I needed to try it as a novel first and foremost. Then immediately some part of my brain was like, you’re not a novelist, put that down. [laughs]

AD: Had you written fiction before this?

EH: Only short stories. A screenwriter and TV showrunner friend of mine created a short fiction publication webzine called Popcorn Fiction. I had a few things published in that space, but I had not gone for what I would call, long distance running.

AD: At the center of the book are these two ideas, predictive analytics and past life hypnosis. I feel like you could spend two hours just explaining those two concepts. You’re also doing it with these characters who are thoughtful and analytical, who intellectualize everything, including their own feelings. You seemed to go, this is a novel. It can be internal. Let’s lean into all of that.

EH: Right. Outside of creating a whole new imposter syndrome for myself, that felt like the best space to explore these characters and allow them to be who they felt like they needed to be.

AD: Without spoiling too much, talk a little about this idea at the heart of the book about souls and reincarnation and where this came from.

EH: Two different desires or needs fed the core of this novel. The first was, I have a real fascination with reincarnation and past lives in the fiction space. One of my favorite movies is Dead Again. I think I referenced it very briefly in the novel. I felt like that’s the hat tip to make.

I listen to certain artists and progressive metal groups, and there was a big operatic album that focused on past lives. And it was a murder mystery. It was called Scenes from a Memory, which is an album by Dream Theater. I finally acknowledged that I clearly kept coming back to this space and thought, what story could I tell in there that is sort of new and different from that.

That finally intersected with, over the course of the pandemic, I had lost a handful of people in my life. Not necessarily all of them from COVID, but from other things that just wound up colliding. I had a deep sense of grief that I didn’t know what to do with.

My analytical brain started poking at the idea of past lives and reincarnation and happening upon this idea that there is likely a finite number of souls in order for the idea of reincarnation to even happen. Because if you have a new soul with every new baby born, then there’s no space for that idea.

That then led me down the path of, it’s possible that if there’s a finite number that we run out of souls, and we have too many bodies, and therefore you end up reincarnating in the same life cycle as you’ve been before. That became a huge cathartic moment for me emotionally as this idea of the people that I liked or loved in my life and didn’t get a chance to spend as much time with them, maybe that they are still in some Venn diagram involved and living good lives regardless.

AD: The book’s two heroes, or three if we include Marigold, are constantly confused about what’s happening. The villains have this community and this connection, and what the heroes want, in this very twisted way. They’re on their back foot a lot constantly. But also just emotionally, there’s that disconcerting aspect to it.

EH: The Enlightened villain is a very scary opponent.

AD: That’s very true. I was curious about the screenplay format. I’ve read your script for Arrival, and there’s a way that some screenwriters think about the page like a poet in a certain way. In terms of rhythm, using the white space, in ways that affect how people read it. A novel is a very different kind of writing, but I am curious about how thinking in those terms kind of carried over or didn’t.

EH: They did carry over. I would say my early draft felt still too much like I was asking myself where the camera went. My editor, Zach, bless his heart, was very patient with me. The red line first draft had so many instances of “too much screenplay language here.” [laughs] You have time, you have real estate, you have an empty house, Eric. So I began furnishing it.

AD: I also mean in the sense that you can approach a screenplay where it’s about action and dialogue, but there’s another way to approach it. I remember reading Walter Hill’s Alien screenplay.

EH: Oh my God, yes. Talk about a poet.

AD: He writes in a way that clearly influenced you where it’s about tone and mood and conveys so much.

EH: It does. Walter didn’t need to rely on like camera angles or over flowery descriptions and narrative passages. Which you often find specifically in science fiction, when you’re dealing about spacecraft or other kinds of things. You end up feeling like you need more real estate on the page to devote to talking about what it looks like.

Walter managed to do all of that in the space of a haiku. It was incredible the way that he could parse everything down and just be very specific and and careful about his description.

Also at the same time, what I loved about his draft of Alien was that it gave you the quietness of that movie. That I think is something that wouldn’t necessarily have been in Ridley’s final piece had Walter not guided them to that concept. That there was an alone-ness, especially in the first half hour of that movie, before becoming more and more phrenetic.

Also, you’re building essentially a transitory document. You’re creating an instruction manual. So what you want to do is make sure that you’re not, or at least I don’t know if this is everybody’s philosophy, but I so rarely get to talk about my philosophy for screenwriting so that I’m just going to jump on this, Alex.

You want to be evocative for the department heads that are going to take this and run with it. You know, the production designer, the costume designer, obviously your director and the DP.

But you don’t want to be prescriptive. You want to say, here is the, here are a handful of keywords that allow me to see the movie in my head. These are seeds that I’m going to be planting in your brains. And you’re going to take that and turn it into a full production.

But the more time you spend on those, the more words you devote to that or commit to it, sometimes the more cumbersome the story gets. You also can discover that if you get it too novelistic in the script—with certain rare exceptions, I say. Barry Jenkins is an exception. He’s a novelistic screenwriter and he pulls it off. There’s something very elegant about his style that I don’t see in others.

Beyond that, you can end up accidentally committing far more to a page and you’re running beyond the one minute run time per page. So that suddenly you have 110 page screenplay, that’s actually a two and a half hour, three hour movie, just because you put too much into it.

AD: In that sense, did running a TV show as you did help in terms of writing a novel? Because you weren’t just making a transitory document.

EH: I learned a lot of lessons from show running that informed my writing in both features and TV beyond that. And it bled into the novel. It bled into thinking more about how are these other people going to do their jobs well? What can I do now at this stage, on this page, that makes their jobs easier? That expresses something that just can bypass any confusion or issues. The biggest revelation I had was in discovering a very early draft of Tony Gilroy’s script for The Bourne Identity.

In his early drafts, in his studio drafts, he does not use slug lines. For the uninitiated, slug lines are essentially where you have the location and whether it’s an exterior or an interior, if it’s day or night. It’s a very useful piece of information when you get into production. It’s just an accepted norm for writers.

I found it fascinating that he didn’t have it at all. He just had a “cut to” over on the side. I asked him at a Q&A, why don’t you not use slug lines in your early drafts?

He said, because I want to get better at transitions. I want to know the relationship between the last image of one scene and the first image of the next. He said, I’ve discovered that when I build that chain link much stronger and I show the relationship between those two scenes, it protects them from a studio executive or from someone else who decides they maybe want to cut something.

The editor immediately understands that relationship. And so you end up with a first assembly in editorial that is much farther along in the process than otherwise. I found that fascinating.

AD: That is interesting. I guess I just meant as a show runner you were writing something to specifically communicate with a lot of different people with different mindsets. I would imagine that impacted your storytelling and writing this.

EH: I don’t mean to be vague about it, but it’s refining your ability to put yourself in other people’s shoes or other people’s perspective. The more you do that, the better you are at, I think, any kind of storytelling really, because then you can go from various characters, including characters that you would never be able to embody yourself.

Like that’s not something that you’d be comfortable with, but you need to for this exercise. Sometimes it is a case of getting as granular as what car someone drives and what’s in the glove box.

Where is the fuel gauge? Are they somebody who can’t stand when it goes below half a tank or are they constantly riding it? What does it say about them? What’s on their calendar? Do they put a lot of people’s birthdays on their calendar or is it just meetings? What does that say about them?

AD: Talk a little about Grant’s job and predictive analytics.

EH: It is a strange department. It’s based on a real department, but that department didn’t have this name. It was Homeland Security. It was a task force or a team that was just dedicated to tracking down anybody who had been quote unquote “prophetic” about the falling of the towers on 9/11 to make sure that they were not associated with Al-Qaeda. Then it became a catch-all.

Likely it’s been dissolved for years now. However, in my reality, they kept going and they just wound up being a dumping ground for anybody, any sort of like charlatan out there who had their local cable access show and was grifting about this or that routine.

AD: In The X-Files, I think part of the origin was all these random unexplained files got shoved into the X file cabinet because there was nothing else in that drawer. It felt a little like that.

EH: Very much. And The X-Files showed up at a very formative time in my life. That’s a show that stayed with me for a long time. It’s the kind of content that I miss regularly from contemporary series.

Some of that bled into this, including the the two-hander of a true believer and skeptic. So Grant’s job is one that has him constantly disprove the belief in the other, essentially something far beyond the most basic nuts and bolts of reality.

He’s constantly been able to do that. He has, I would say, a quirky boss who’s clearly obsessed with sleight of hand magic in his own right, and came from that background. Grant’s upbringing has really pulled the magic out of magic realism in his world.

And so his first relationship that opened his eyes to something bigger and even slightly supernatural was a real test of faith. I think it’s the thing that was the bridge that allowed him to cross that divide into maybe accepting this new reality once he encountered Sarah and the simultaneous lives.

AD: This might be something of a spoiler, but when I first read the book, I thought, this ends the way the first Back to the Future movie ends.

EH: [laughs] I was thinking more like Edge of Tomorrow.

AD: [laughs] It ends in a way that works, but is also slightly annoying. Is there another book coming soon? I hate asking that question, but you know why I’m asking.

EH: [laughs] If I am fortunate enough to have the privilege to return, I have the next book in me. I would love to continue writing in this space.

I may not have much choice with the weird state of my business in film and TV right now. It’s just a weird time. I’m working on the Pacific Rim prequel series. I’m developing that with Amazon, but their head of scripted just left and somebody new came in, and who knows what will happen.

AD: Simultaneous was a lot of fun. I’m intrigued because I think it was Grant who pointed out, this could mean the end of the world, and you think through the implications and go, wait a minute. It actually could.

EH: It’s very dangerous. [laughs]

AD: I’m curious to see how you will either end or not end the world in the sequel.

EH: I would say my favorite genre right now is hopepunk, and so I would hope that we could pull this out.

***