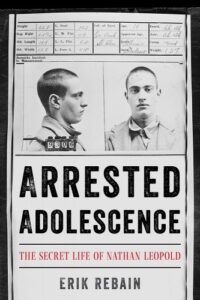

In Chicago, on May 21st, 1924 Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb murdered 11 year-old Bobby Franks, in what was termed at the time a thrill-killing. Leopold and Loeb were both academic geniuses, sons of millionaires, and lovers. Renowned attorney and foe of capitol punishment, Clarence Darrow was able to get them “life plus 99 years” instead of the death penalty. Loeb was murdered in prison in 1936 and Leopold took charge of his own publicity and was released from prison in 1958. He lived out his years quietly in Puerto Rico until his death in 1971. Little has been written about his post-prison life. Erik Rebain , an archivist who works for the Chicago Tribune and Chicago History Museum has spent a decade researching Nathan Leopold’s life. In Arrested Adolescence: The Secret Life of Nathan Leopold he uncovers sides of Leopold we’ve never seen before.

JD: What first drew you to the Leopold and Loeb case?

JD: What first drew you to the Leopold and Loeb case?

ER: I first heard about the case when I watched a documentary about it in class during my senior year of high school. Back then I kept mixing up which was Loeb and which was Leopold, but I was so curious about the motive for the murder and what the relationship between them had really been like. Later, after I had read a couple books, my interest shifted to trying to discover what their childhoods were like, to hopefully get a better understanding of how they developed. Then as my archival research began, I wanted to understand who they became after the crime, and how it changed, or didn’t change them.

JD: I definitely think of you as the go-to scholar of this case. What was your experience like researching and writing this book? How did you keep it fresh for yourself?

ER: Well, thank you! I researched this case casually for a while. It started when I was in community college in Michigan, and a couple of times a year I would come to Chicago to spend a week in the archives, taking pictures of box after box of letters, then I would go home and read and take notes on them all until I ran out and had to come back for more.

At that point I didn’t have a book in mind, I just wanted to know more. But as I delved into Leopold’s later life, I couldn’t believe no one had written a book about it yet. And as the years went by and new books still only explored the crime, I finally realized that if I wanted a book like that to exist, I would have to write it myself.

As for keeping things fresh, there’s so much material that it’s hard to get bored! If I get tired of looking into the 1924 crime I can research Stateville prison, or Great Lakes shipping in the 1800s, or Puerto Rican gay bars from the 1960s and it’s all still relevant. It’s a never-ending rabbit hole.

JD: When I was writing my gender-swapped Leopold and Loeb novel, Jazzed, I felt a real need to look at the outside forces that oppressed queers in the 1920s up through the 2020s. But in Arrested Adolescence, I definitely got the idea that Leopold himself would not be interested in those matters. It makes me think of Patricia Highsmith, who wrote brilliantly about amoral protagonists and was pretty openly amoral herself. What do you think Leopold would make of your portrayal in this book?

ER: Leopold may not have been an activist for the queer community, but he did keep an eye on things. He and a gay friend would send each other newspaper clippings of hate crimes committed in their area. And Leopold celebrated when he found out a state had changed its laws to decriminalize homosexuality.

As for my book, I’m sure Leopold wouldn’t be pleased that some of his secrets and less socially acceptable activities are discussed. I’d love to get his reactions to it though, to get his side of the story I tried to tell.

JD: I know we’ve discussed the evidence that makes it pretty clear that Dickie Loeb actually killed Bobby Franks, and your book only underscores that point. What do you make of those who still say it was Leopold?

ER: Nothing is certain, there’s evidence on both sides, so I don’t think it’s wrong to speculate on who was driving the car and who was in the back seat and physically killed Bobby. I just think there’s a lot more evidence that it was Loeb, not Leopold. On Leopold’s side there’s the psychiatrists who said under oath that Loeb told them he did it. There’s the fact that Loeb is the one who in previous crimes always carried a taped chisel with the idea that he could use it to knock someone out, and a taped chisel was used to knock Bobby unconscious. There’s the fact that Leopold almost always drove when participating in their other crimes. He was the one to rent the car they used in the Franks murder and it was the same make as his own car. And Loeb couldn’t remember the streets that he supposedly drove down during and shortly after the murder while Leopold could.

The big piece of evidence on Loeb’s side is an eyewitness, who are notoriously unreliable, and a study actually showed that about half of wrongful convictions were because of the faulty memory of eyewitnesses. In this case, a chauffeur said he saw Loeb driving at 4:30 that day, a time when Leopold and Loeb claimed they weren’t driving. The chauffeur drove that route to and from a school in the neighborhood at least twice a day, and it was only a couple of blocks from Loeb’s home, so I think it’s definitely possible that he could be misremembering the day he saw Loeb. This memory was also reconstructed when the man was told of Loeb’s confession 10 days after the crime, and the prompting makes it even less reliable to me. So I feel that the other evidence outweighs the possible eyewitness.

JD: The budding friendship between Leopold and Roy Cohn really made me sit up and take notice as I read your book. Narcissist is such an over-used word, but it certainly seems like Leopold, Cohn, and Donald J. Trump are all cut from the same self-serving cloth. Why do you think Meyer Levin painted a much more sympathetic picture of Judd Steiner, whom he based entirely on Leopold?

ER: Levin was reintroduced to the case while Leopold was in the middle of a positive publicity campaign as he tried to get paroled from prison. And Levin seemed to genuinely believe Leopold’s story of rehabilitation, he wrote an article calling for his parole and spoke at one of his parole hearings. Levin also didn’t have the access available to really get to know Leopold, and he hadn’t shown his true colors outside of prison yet. And Levin was steeped in the Freudian psychology of the time, and found a lot of truth in the 1924 psychiatric reports about Leopold seeing himself as a slave to Loeb’s king (though Leopold later revealed that the king-slave dynamic wasn’t true). All of that got mixed together when Levin wrote Compulsion, his novel about the crime in 1956.

In creating Judd, the fictional Leopold, Levin combined the images of the rehabilitated Leopold that were popular at the time and his Freudian-inspired reading of the psychiatric reports. So Judd is a more sympathetic, but also a more pathetic character. He’s a slave to the Loeb character and does whatever he says, though his unconscious goal in committing the Franks crime is to kill the girl within himself and be reborn as a boy so he can rid himself of homosexuality, become masculine and heterosexual. Some of Leopold’s culpability is taken from Judd, but he also lost a lot of Leopold’s personality and sense of humor, which makes him in some ways less real, and less sympathetic, at least to me.

JD: If you could ask Leopold three questions what would they be (and why)? And what do you think he might say?

ER: That’s difficult, because I think it would be hard to get him to tell the truth about the questions I’d like to ask!

I would like to ask him why he’s convinced that though it was a prisoner named James Day who confessed to killing Richard Loeb, why Leopold was convinced that it was Day’s cellmate George Bliss who planned and was to blame for the murder. I’d like to know what the relationship and tension between Loeb and Bliss had been that would make Leopold think that. I have no idea what his answer would be! There’s been some speculation that Loeb was trying to control some prison rackets, trying to amass power in prison, and perhaps that’s what Bliss was trying to get rid of, but I really have no idea.

I’d also be interested to get his opinion on the huge increase in the number of incarcerations in the United States since his death. He was fighting to abolish prisons back in the 1960s and 70s when there were still around a half million incarcerated people in the Unites States. Now it’s at around 2 million. I’d be very curious to get his take on what went wrong. I’m sure he’d be disgusted by the state of things.

I’d also be curious to get his take on the meteoric rise of mass shootings we’ve been witnessing. He could sometimes be fairly insightful when it came to analyzing the motivations and patterns of criminals, so I’d be curious about his take here.

JD: I’m curious if you read true crime yourself, or what you read besides works about Leopold and Loeb?

ER: Nope! I actually haven’t read or watched any true crime since undergrad, unless it’s been connected to researching this case. I’ve been on a kick of reading historical queer novels lately, my favorites are those written before the 1970s. Maurice by E M Forster is my favorite, but I was also really surprised and delighted by Christopher Isherwood’s The World in the Evening and Cassandra at the Wedding by Dorothy Baker.

For more on Erik Rebain click here.

***