During my research for The Alaskan Blonde, a true crime book that reexamines the 1953 murder of wealthy Alaskan businessman Cecil Wells, I was amazed to learn that Erle Stanley Gardner, the creator of Perry Mason, had been asked to recommend a private eye to the Wells family.

Gardner’s choice was straight out of one of his novels: Glen E. Bodell, who he described as “a man whose life would have been far from gentle, who carries several bullet scars, and would no sooner think of going out without his gun than without his shoes.”

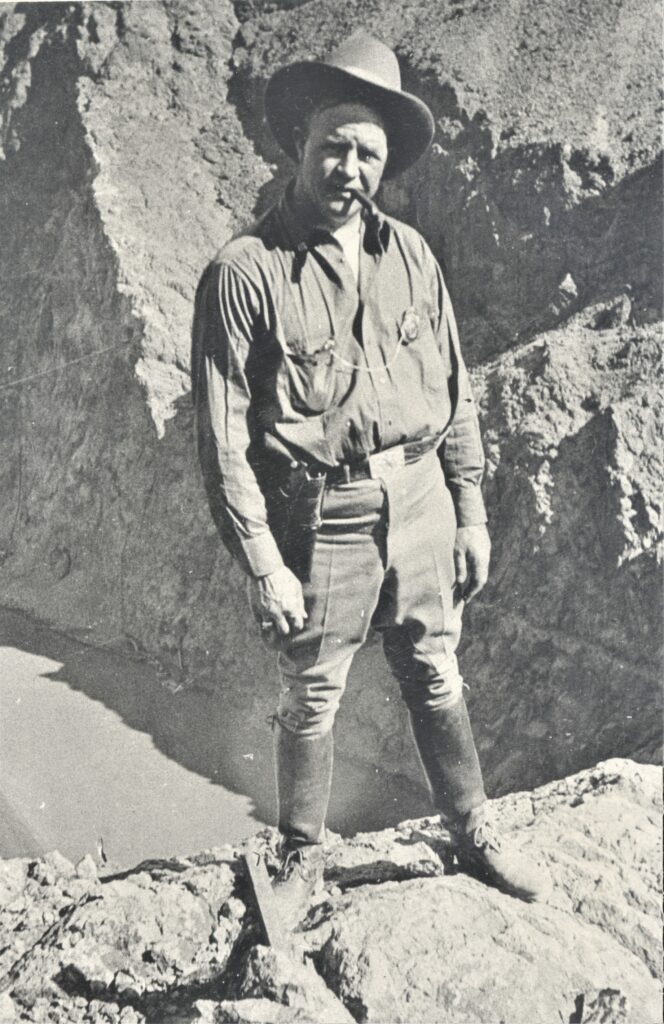

Known to all as “Bud,” the cigar-chomping Bodell had been a teenage racer in his hometown of Salt Lake City, and earned his reputation as a bruiser while he and his team marshaled the hundreds of employees working on the Hoover Dam. He had several other law careers, and was the first registered private eye in Las Vegas (his license plate was “ONE”).

Bodell first came to Gardner’s attention during the “Court of Last Resort,” a series of short stories he began writing for Argosy magazine in 1948 that were the basis of a best-selling book in 1952.

The stories were based on real-life crimes that were compiled by Gardner and his specially-assembled volunteer team of expert freelance scientists, lawyers, detectives, police officers and journalists as potential miscarriages of justice.

One of the Argosy stories was based on Emma Jo Johnson, 32, who had been convicted of second-degree murder of her elderly landlady, Jane Jones, following a hair-pulling argument over mail at a small hotel in Las Vegas on May 23, 1951.

Starting in March 1953, a series of letters about the case flew between Gardner and fellow “Court” member LeMoyne Snyder, medicolegal expert and author of Homicide Investigation, a seminal book for medical examiners, police investigators and members of the legal profession.

Snyder and Gardner were convinced Johnson had been unjustly convicted because, on re-reading the autopsy evidence, they felt her death in hospital two weeks after the incident was more likely a subdural hematoma related to a long-term condition, rather than the direct result of Johnson’s actions – which included the allegation she hit Jones in the head with a can opener.

Mrs. Diane Wells stares blankly as she poses for photographers in the Federal building in Seattle, Wash., Nov. 5, 1953, shortly before announcing she would return to Fairbanks, Alaska, to face a charge of murder in the slaying of her husband, Cecil Wells, 51, wealthy auto dealer and president of All-Alaska Chamber of Commerce. Also charged in the murder is musician Johnny Warren, who is being held in Oakland, Calif. (AP Photo/Ed Johnson)

Mrs. Diane Wells stares blankly as she poses for photographers in the Federal building in Seattle, Wash., Nov. 5, 1953, shortly before announcing she would return to Fairbanks, Alaska, to face a charge of murder in the slaying of her husband, Cecil Wells, 51, wealthy auto dealer and president of All-Alaska Chamber of Commerce. Also charged in the murder is musician Johnny Warren, who is being held in Oakland, Calif. (AP Photo/Ed Johnson)

A potentially-vital piece of evidence supporting that innocence theory was a letter sent to Johnson’s attorney. It stated that Jones was subject to blackouts, and that she said she had passed out and hit her head the day before her death – and been unconscious for several hours. The letter was anonymous however, and arrived barely an hour before the end of the trial – too late to have an effect on the verdict.

Bodell carefully tracked down the letter’s author, Jones’ physiotherapist, and he also gathered witness statements from other people about her medical condition.

Gardner then began a strong letter-writing campaign to judges, wardens and other officials who had been involved in the case, and in November 1953 he and Snyder both testified at a special parole hearing in Carson City, Nevada.

In January 1954 prisoner number #6904 was set free after serving three of her 10–12-year sentence, and Gardner writes about getting a call from Johnson soon after her release. She was at the home of Bodell and his wife Irma, where she had married her fiancé Jack Wengert, 44, who had initially written to Gardner after reading one of his Argosy stories.

Gardner was completing his Argosy version of Johnson’s case when he got that call from the family of Cecil Wells.

The facts of the case were that Wells had been shot dead in his bed, and his wife Diane, 31, was badly beaten. Fairbanks Police thought another in a series of high-profile robberies-turned-violent, but then someone suggested they ask the glamorous Diane, who was Cecil’s fifth wife, about her relationship with a Black musician called Johnny Warren.

Despite the murder happening in far-off territorial Alaska, the film noir mix of murder, money, sex and race was irresistible to Newsweek, Time, Ebony, Jet, pulp magazines and even the international press.

Diane and Warren were charged with first-degree murder, but the police and FBI could not find the murder weapon, and bloodied fingerprints from the crime scene were too damaged to yield results.

With the Fairbanks trial of Diane and Johnny Warren fast approaching and a conviction by no means certain, the Wells family wanted answers – and fast. Money, careers and reputations were at stake, and there were even whispers that this killing could derail Alaska’s quest for statehood.

Gardner surely had no hesitation in recommending Bodell to help them.

Bodell soon learned that the Wells family had already hired Clyde Dailey and Wendell Paust, two “on vacation” Seattle police detectives, and Bodell’s handwritten note from the time says there was a dedicated phone line from Seattle to Fairbanks installed, presumably to simplify communication between them.

Dailey and Paust had already administered some lie detector tests in Fairbanks, though Johnny Warren had refused to take one. Bodell was en route to Fairbanks on March 9 when he learned that Diane had taken an overdose of barbiturates in a Hollywood hotel room. A Los Angeles Times report about those lie detector tests was found among her possessions.

Warren’s trial was immediately postponed, so Bodell went back to Las Vegas – but he returned to Hollywood in May to appear alongside Gardner and Snyder when Emma Jo appeared on This Is Your Life. She was clearly delighted to see them all, especially the man she called “Uncle Erle.”

Bud Bodell on edge of Black Canyon, image provided by Boulder City Hoover Dam Museum

Bud Bodell on edge of Black Canyon, image provided by Boulder City Hoover Dam Museum

In 1955 Bodell was appointed deputy coroner of Las Vegas, a post that saw several suspicious deaths pass through his office, including that of Tony “The Hat” Cornero, the Vegas pioneer behind the Stardust Casino. Bodell eventually spent close to two decades on the Strip, and became head of security at the famous Sands Hotel and Casino. He died two days before Christmas in 1979.

As for Gardner, his “Court of Last Resort” was adapted for an NBC television series in 1957, the same year that Raymond Burr began what would become his decades-long portrayal of Perry Mason.

The murder of Cecil Wells was never solved.