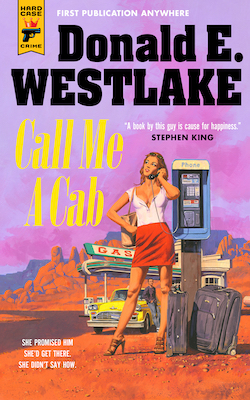

She hailed me on East 62nd Street, not far from Bloomingdale’s. She was an attractive girl, wearing big-lensed sunglasses against the June glare, and carrying two plaid suitcases, one of which she waggled at me as I rolled down the street. “Say ‘Kennedy,’ ” I whispered, and eased the cab to a stop.

She hailed me on East 62nd Street, not far from Bloomingdale’s. She was an attractive girl, wearing big-lensed sunglasses against the June glare, and carrying two plaid suitcases, one of which she waggled at me as I rolled down the street. “Say ‘Kennedy,’ ” I whispered, and eased the cab to a stop.

Opening the rear door, she shoved the suitcases in first, then followed, slammed the door, shoved the sunglasses up on top of her head, and said, “Kennedy.”

“You got it,” I said, and started the meter with a smile. Not only is the long expensive run from Manhattan out to John F. Kennedy International Airport in Queens one of the joys of a cabby’s life, but there’s no pleasanter way to drive anywhere than with a good-looking woman in the rearview mirror.

Unless, of course, she’s crazy. And in this instance the early signs were not good. This girl did not sit back in the seat as I started off, nor did she cross her legs and look out at the passing world, nor did she take a compact from her shoulder bag so she could study the present condition of her face; all the normal things a good-looking young woman does when settling down alone for a long cab ride. What she did do was talk to herself, muttering phrases I couldn’t quite hear. And she kept putting her hands up to both sides of her face like the blinkers on a horse, running her fingers through her long brown hair and then tossing the hair backward in a heavy double wave. And she frowned a lot, and made strange unpleasant faces, and stared at the floor or at the back of my neck. And sat forward on the seat, very tense and upset.

Part of the reason this behavior discomfited me was the lack of a safety partition between the back of my head and the passenger space. In New York City, all the major-company cabs are required to install that safety partition, but the law says private cab owners can decide for themselves, and the private owner of this particular Checker (who just happened to be my own father) had decided not to go the expense. Normally I like it that way, preferring the increased opportunity for friendly conversation and other human contact, but human contact with a crazy person is where I draw the line.

I endured it all the way down Second Avenue and through the Midtown Tunnel, but after I’d paid the toll and accelerated up to speed on the Expressway and she still hadn’t settled down I felt I had to do or say something to alter the situation. Frankly, she was making me nervous. So I looked in the mirror and I called, “Excuse me!”

She flashed a quick, irritable, distracted look. “What?” I said, “You a jumper?”

At least I had her attention. “What?”

“Friend of mine had one in his cab,” I explained. “A suicide, you know? She wanted to jump off a building, but she was afraid of heights.”

She was staring now like Medusa. “A suicide?”

That was the wrong subject. “Afraid of heights,” I corrected her. “Try to keep up, will you? This girl’s idea was, she could get the same effect if she jumped out of a cab doing sixty.”

“I’m not a suicide,” she said. And it was true she now looked more outraged than despondent.

“That’s good,” I said, “because it won’t work. There’s too much air pressure against the door at this speed, you couldn’t get it open.”

She glanced at the door, then rather angrily at me. “I’m not a suicide,” she repeated.

“Fine.”

After that she settled back in the seat at last, obviously thinking things over, and I concentrated on the traffic until she herself picked up the conversation, out past the cemeteries, telling me, “I just have a decision to make, that’s all.”

So I gave her my philosophy, in a nutshell. “Don’t do it.”

“Don’t do what?”

“Don’t make decisions. They can only cause trouble.”

“But I promised,” she said. “And I always keep my promises. Always.”

“Then don’t make promises.”

She smiled, a bit ruefully; meaning, it’s too late not to make this particular promise. Well, it wasn’t too late to break it, but who am I to lead another person out of confusion and into the light? I kept my advice to myself, and once again the conversation lapsed.

And once again she was the one to pick it up, just as I made the transfer from the Expressway to the Van Wyck, saying as though there hadn’t been any pause at all, “It’s about getting married.”

“Married?” I don’t believe in marriage. “Good luck,” I said, and some irony may have crept into my voice.

“It isn’t right,” she said. “I just keep turning the poor guy down.”

“Maybe he’s the wrong guy.”

“He’s the right guy,” she insisted. “He’s sweet and understanding, he’s handsome and rich, he loves me and I love him—what more could I possibly want?”

“Thursdays off?”

“I don’t know what I want,” she said, shaking her head. “It’s just such a big decision, that’s all.”

“Mm hm.” I’d already given my advice on decisions.

“For two years I’ve been trying to marry him,” she said. “That poor guy, I’ve left him waiting at the marriage license bureau, at the church, and on the JP’s front porch.”

“He puts up with a lot.”

“He’s very understanding. That’s why I love him so much.

But now he says he can’t wait anymore.”

“Oh, yeah?”

“He says he wants to marry me, but he says he also just wants to get married.”

“Determined fella.”

“So I promised him, faithfully, just now on the phone, I’m coming out to Los Angeles—”

“That’s where he is, huh?”

“And when I get off the plane, I’ll either say yes or no. If it’s yes, we’ll get right in his car and drive straight to Nevada and be married today.”

“Wow,” I said.

“If it’s no,” she said, “he says we’ll shake hands and part, and I can take the next plane back to New York.”

“So it’s do or die. The crunch. Down to the bottom line. This is the nitty gritty.”

“That’s right,” she said. “Five hours from now I’ll be in Los Angeles, and I have to be sure by then.” She shook her head fiercely, agitating her heavy hair. “How can a person make a decision for their whole life in five hours?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “With me the question has never come up.”

And once more the conversation waned, as she settled back in the seat, biting on the knuckle of her right thumb and brooding about this crisis point in her life. I continued to drive, she continued to brood, and then I became aware that she was staring at the back of my neck; fixedly, the way I imagine a vampire would. I was beginning to get nervous again when she called out: “Say.”

“Yeah?”

“This sign here,” she said. “Ask Driver For Out Of Town Rates.”

Ah; that was the notice glued to the back of my headrest, so it wasn’t my throat she’d been studying after all. I said, “Yeah?”

And she said, “How much to Los Angeles?”

“A hundred million dollars,” I said.

“No, I mean it,” she said.

She couldn’t possibly mean it. A little annoyed, I said, “Come on, Miss.”

“Listen, umm—” she said, and leaned forward to look at the license mounted in front of the glove compartment. She wanted my name. “Thomas,” she said. “Listen, Thomas, I’m serious. I told Barry I’d make up my mind by the time I got to Los Angeles, and I promised him I’d leave today, but I just can’t do it in five hours. How long would it take to drive there? Five or six days?”

I was reluctant to be in this conversation at all. “Probably,” I said.

Her expression became almost dreamy. “Away from all distractions,” she said. “Away from the office, just driving, plenty of time to think. By the time we got there I’d know, I’d be sure of myself.”

It was time to bring her down from the clouds, so she could catch her plane. “It’d be goddam expensive,” I said.

“How much?”

“You want me to find out?”

“Yes, please.”

So I switched on the two-way radio. We belong to one of the radio-dispatch outfits—Speediphone Cabs—but unless a fare leaves me in some outlandish backwater I prefer to cruise and find my customers on the street. The kind of people who phone for a cab instead of going outside and hailing one usually live in outlandish backwaters themselves, where there aren’t any cabs to hail. In any event, the radio had been off, but now I switched it on, and immediately the cab filled with the harsh voice of Hilda The Dispatcher: “…to Madison and 35th. One-eight.”

Pressing the button on its side, I spoke into my mike, giving my call number: “Two-seven.”

“One-eight,” Hilda insisted, that being the guy she’d decided to talk to next.

Phooey. “Two-seven!” I said, more forcefully. “One-eight!” she said, much more forcefully.

So I tried tact. “I’ll be one-eight if you want me to be one- eight, Hilda,” I said, “but I’m really two-seven.”

“Tom? Get off, I’m trying to talk to one-eight.”

“But I’m ready to talk now.”

Hilda’s sigh came across the airwaves like static. “All right, Tom,” she said. “What is it?”

“I got an out of town, she wants a price.”

“Where to?”

“Los Angeles,” I said.

There was a little silence, and then Hilda said, “One-eight!”

“Listen, Hilda,” I said, “this is on the level.”

“A cab to Los Angeles?” She remained dubious, for which I could hardly blame her.

“That’s right,” I said. “The customer’s in the cab, she wants a price.”

“Jesus,” Hilda said. “Shut up, one-eight, I got a problem. Tom? I’ll get back to you.”

“Right,” I said, cradled the microphone, and turned the receiver volume down to where I could barely hear it.

The passenger said, “Shouldn’t we head the other way now?” Were we really going to Los Angeles? So far everything was still on the meter, so it didn’t matter where we went. “Sure,” I said.

We were at that moment arriving at the junction of the Van Wyck and the Belt Parkway, just before the airport, and we did a sweep-around of rare and singular beauty, hardly slowing down at all. I took the second Parkway exit (northbound), looping down and to the right away from the Van Wyck like a fighter plane peeling off in a World War Two movie, then swept around onto the Belt, ran under the Van Wyck, took the next exit curving up and to the right, came out onto the Van Wyck in the opposite direction, and laid out toward Manhattan.

The passenger was very excited. She kept looking out the rear window, as though to see the plane she wasn’t catching, and she kept saying things like, “It’s the only way. It’s the only thing that makes sense. I can be sure of myself. Barry will under- stand.” That last part was said with a little less excitement and conviction, but she quickly rallied and repeated some of the other sentences some more.

It was perhaps eight minutes before the intermittent tiny squawking of the radio squawked my call number, and then I turned up the receiver volume, grabbed the mike, and said, “Right here.”

“Four thousand dollars,” Hilda said. “Plus your expenses.” Her tone of voice said, There. Now leave me alone with all this nonsense.

I looked in the rearview mirror. “Did you hear it?”

“Four thousand dollars.” She’d heard it, all right; she was pale and worried. “I have that much,” she said, more to herself than me. “In my savings account, for income tax. I could stall, just pay the interest—” She frowned and chewed her lower lip, working it out, while I drove not too rapidly westward. Then all at once she sat up straighter, her expression full of determination, and said, “Yes.”

“You’re sure?”

“It’s worth it,” she said. “For peace of mind, the rest of my life? It’s cheap. The IRS can wait.”

“Okay.” Into the mike I said, “She says it’s a go. Tell my father, will you?”

“Cash, or certified check,” Hilda said.

“That’s fine,” the passenger said. “We’ll just stop by my bank, and we’ll be on our way.”

__________________________________