Riverview Amusement Park, Chicago, August 1915

There he was again, smoking a cigar in front of the Infant Incubators. A white man not much taller than Pin—and she was small for her age and looked twelve, rather than fourteen—but too tall to be a midget. Something stealthy and twitchy about him: every few minutes, his head would twist violently and he’d punch the air, fending off an invisible assailant.

There was no attacker. Crowded as the amusement park was, Pin saw no one anywhere near him. The young mothers dragging their kids into the Infant Incubators building to escape the heat stepped off the sidewalk onto the Pike to avoid coming within two feet of him. He was a dingbat.

She ran her sweaty hands across her knickerbockers, removed her cap to fan her face. She’d seen the weird little man at the park often—three or four times a week he’d be standing near one of the rides, always watching, watching. He never seemed to change out of the same soiled work clothes. Trousers, shirt, a dark-blue canvas jacket.

***

Heavy boots. A white boater hat with a stained red band; sometimes a bowler.

Today it was a boater. He never rode any of the rides, and never seemed to partake in any of the attractions. Once she’d seen him outside the Casino Restaurant, drinking a glass of beer and eating a sausage. A few times he’d been with another man, older, the two of them like Mutt and Jeff in the funnies: one tall and skinny, the other short with that grubby mustache and dinged-up boater.

But lately the weird little man was always alone. And all he ever seemed to do was watch the kids go in and out of the Infant Incubators, hop off and on the Velvet Coaster, clamber into the boats that bore them into Hell Gate or the Old Mill, then back out again.But lately the weird little man was always alone. And all he ever seemed to do was watch the kids go in and out of the Infant Incubators, hop off and on the Velvet Coaster, clamber into the boats that bore them into Hell Gate or the Old Mill, then back out again.

He knew Pin was watching him. She could tell by the way his eyes slanted when he cocked his head, pretending to look in the other direction, the way Mr. Lerwin used to look at her younger sister, Abriana. But the dingbat wouldn’t know that Pin was a girl disguised as a boy. No one knew, except Pin and her mother.

He talked to himself, too. One of these days she’d sidle up close enough to hear what he was saying. But not this morning. She tugged her cap back down, felt in her pocket for the Helmar cigarette box Max had given her half an hour ago, along with a cuff to the back of her head.

“Don’t you go dragging your feet like last time,” he’d said. “I can’t afford to lose business.”

“It was raining. Lionel ain’t gonna ditch you.” “It’s not raining today. Go.”

He raised his hand in warning. She darted out of the dressing room and heard him laughing behind her. “Run, rabbit, run!”

She spat on the pavement, kicking at a squashed stogie, spun on her heel, and headed for the exit gate. When she glanced back over her shoulder, the dingbatty little man was gone.

***

Max always gave her fare to the movie studio or the other places where she delivered hashish cigarettes and dope, though only enough for one way. She never stopped asking him for the nickel, even though that risked getting smacked.

“What about the fare home?” She sat in his dressing room, a makeshift shack even smaller than the one where she lived with her mother, tossing her cap into the air as she watched him get ready for work. “Just another nickel, you got plenty.”

“The hell I do. Tell Lionel to give it to you. That’s his end of the deal, not mine.” Max leaned into his makeup mirror, drew a comma in black kohl along one eyelid. “You’re too lazy to work, boy, I’ll find someone else.”

Before she could duck, he grabbed the cap from her hand and tossed it toward the back of the room, where it fell beneath the cracked window. Pin retrieved the cap, then stepped to an overturned barrel that served as a chair. Scattered photographs lay atop it, old French postcards that showed the same young woman, dark haired and wearing a black schoolgirl’s uniform. Her waist was grotesquely small, tightly corseted beneath the uniform. Corsets were going out of fashion; these pictures had to be at least ten years old.

Looking at them made Pin feel slightly sick. The woman’s tiny waist made it look as though she’d been cut in two, the halves of her body held together by a strip of black ribbon: if you pulled at it, she’d fall apart. Pin quickly gathered the photos and shoved them onto a shelf covered with similar photographs, then settled on top of the barrel to gaze, mesmerized, over Max’s shoulder into the mirror.

She’d never known a guy who wore makeup. She’d heard of fairies, of course. Ikie and the other boys in the park sometimes pointed them out to her at night. To Pin, they looked like ordinary men. A few were dudes, flashy dressers who wore spats and striped waistcoats and nice shoes, but she’d seen plenty of dudes fondling women in the dark rides. Some fairies looked like workmen, others businessmen. Some might be with their wives, or even children.

“How can fairies have kids?” she’d asked Ikie. He shrugged. “Hell if I know.”

Once in the Comique, the park’s movie arcade, she’d seen a pair of young men standing together in front of a Mutoscope, dressed like they were headed for a dance hall. The men took turns peering into the viewer, and for a fraction of a second their fingers had touched—deliberately, one finger caressing the other before the hand was withdrawn. The sight had filled her with an emotion she’d never felt before: a cold flash, neither dread nor fear yet partaking of both, along with a pulse of exhilaration, as though she sat in the first car of the Velvet Coaster as it began its plunge down the tracks.

Max wasn’t a dude, or a fairy, as far as Pin could tell. She followed him sometimes around the park, always careful to keep a safe distance, half hoping and half fearful that she might see some proof that he was…something. Some look or touch, a foray into the Fairyland woods and picnic ground, where men were rumored to meet.

She never did. Other than the occasional knock to the head, he never laid hands on her. Offstage he wore shirtsleeves, no cuffs or celluloid collar, and plain dark trousers, indifferently pressed. He had vivid yellow-green eyes, the color of uranium glass. He dyed his hair blond, but that was for the act, like the makeup he painstakingly applied before his first performance and touched up during the day.

His mustache, too, was fake, and only half a mustache. He was Max and Maxene, the She-Male, half man and half woman, appearing at ir- regular interludes in the last tent on the Pike, just past the Ten-in-One. Not a real freak, but a gaffed freak, like most of the others.

According to Clyde, the Negro magician, Max had been an actor before he arrived in Riverview early that summer. “He played Romeo at the Hudson Theatre. Shakespeare.”

“Romeo?”

Clyde had given her a sharp look. Pin thought he was handsome enough to be an actor himself—tall and broad chested, with beautiful chestnut-brown eyes. “You think it’s funny he played Romeo?”

She shrugged. “Sure. Look how old he is.”

“He was younger then. They said he was going to be the next Karl

Nash.”

“Why’s he working here, then?”

Clyde shook his head. “What I heard, some little gal broke his heart. That’s the way it goes. He’s just doing this to get by. He’ll find work again when he wants to. Real work.”

Max used her to deliver drugs only a few times a week. Pin wished she had a more reliable source of cash. Like Louie, the kid who worked as a sniper, putting up signs around Chicago that advertised new shows at Riverview. He got three dollars a day for that, plus streetcar fare. Or the boys who worked as shills and made twenty- five cents an hour, winning big prizes in fixed carnival games while the rubes looked on. The rubes never won, and they never saw the boys slipping through the back doors of the concessions to return their prizes—child-sized dolls, five-cent John Ruskin cigars, glass tumblers.

And only boys were used to deliver drugs across town. Hashish and marihuana were considered poison, like arsenic. Heroin was worse—Pin had to get it illegally from a druggist on the North Side

and bring the glass bottle back to Max, who measured the dope into tiny tinfoil packets, twenty for a quarter. Pin dreaded those trips, espe- cially since two policewomen arrested a druggist on North Clark for selling heroin and cocaine to another delivery boy.

Max had a few regular clients—Lionel, a writer at the movie studio; a woman who performed abortions in Dogville; a Negro horn player who played jazz music at Colosimo’s Cafe, a black-and-tan joint, where black people and white people could dance together. The rest were onetime deliveries: students at the university, musicians, whores, vaudeville performers at the theaters along the Golden Mile. Her run to the Essanay Studios was Mondays and Fridays, usually. Lionel made good money, twenty dollars a story, and he pitched three or four scenarios a week.

She knew the work was risky, but it never felt dangerous. If she’d been a fourteen-year-old white girl roaming the South Side or Packingtown, sure. But no one blinked to see a white boy the same age sauntering along the Golden Mile, or ducking in and out of theaters, or Barney Grogan’s illegal saloon, hands in his pockets and a smart mouth on him if you looked at him sideways.

She seldom saw Max smoke hashish. Instead she watched in fasci- nation as he applied his makeup. He made a paste from cold cream and talcum powder and used this to cover the left side of his face; then carefully mixed cigarette ash, pulverized charcoal, and dried ink to make kohl and mascara, which he applied with tiny brushes and a blunt pencil to his left eye.

“Why don’t you just buy ladies’ stuff?” she wondered aloud.

Max laughed. “What do you think they’d say to me in Marshall

Field’s, I went in and asked for some face paint and rouge?”

“The actors at Essanay use makeup. Charlie Chaplin uses makeup. And Wallace Beery.”

“Do I look like Charlie Chaplin?”

After he’d painted his cheeks and lips, he dabbed the edge of one eyelid with adhesive, then affixed a fringe of false lashes made of curled black paper. Last of all, he put on a wig of blond curls. It was only half a wig, like his face was only half a woman’s. The right side had Max’s own bristly stubble on his chin and neck, a web of broken capillaries across his cheek. Blond hair slicked back so you could see where the orange dye had seeped into his scalp. Outside his tent, a ban- ner depicted an idealized version of the real thing: the She-Male’s face split down the middle and body divided lengthwise—natty black suit and shiny shoes, yellow shirtwaist and hobble skirt, the hem hiked up to display a trim ankle.

“Gimme a match,” Max ordered. He tapped a cigarette from a box of Helmars, its logo depicting an Egyptian pharaoh. Pin lit the cigarette for him, and he turned away, leaving her to stare at her own face in the mirror, a luxury she didn’t have in her own shack. Snub nose and pointed chin, dirt smudged across one cheek, uptilted soot-brown eyes, a chipped front tooth where she’d gotten into a fight. A scrawny boy’s face, you’d never think otherwise.

“Look sharp.” Without turning, Max tossed her a Helmar cigarette box, barely giving her time to catch it before he threw her a nickel. She snatched it from the air and he laughed. “Nice catch, kid.”

She grinned at the compliment, pocketed the nickel, and headed out on her run.

__________________________________

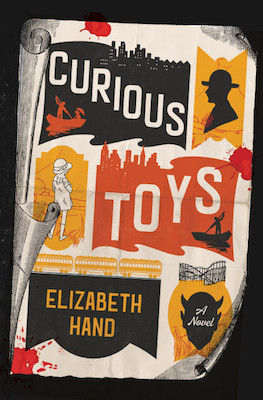

From Curious Toys, by Elizabeth Hand. Used with the permission of the publisher, Mulholland. Copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Hand.