La Paz, barely visible behind the boxes of detergent, is giving herself a bath. Tortoiseshells are my favorite, but I’ll be honest, this cat’s a bit of a bitch. I’m sucking back blood from the scratch she gave me on my finger when a kid in a red hoodie saunters in.

From up the hill. You can just tell. Making sure you can see his labels. That swagger, based on nothing. You can’t even grow pubes, kid, that shitty facial hair you’re attempting’s a dead giveaway. Looking me up and down before sucking his teeth and walking along the cooler aisle like he pays rent on the place.

From up the hill. You can just tell. Making sure you can see his labels. That swagger, based on nothing. You can’t even grow pubes, kid, that shitty facial hair you’re attempting’s a dead giveaway. Looking me up and down before sucking his teeth and walking along the cooler aisle like he pays rent on the place.

“Yo—you carry malt?” he says. “Old E?” Eight-thirty in the—

“Sorry, no,” I say. “We don’t get that in the flats. Bud, Bud Light’s about it. Sometimes Coors.”

“Ain’t got no malt? Damn, son….”

An old lady in a faux-fur coat hobbles in, bee-lines for the counter. Nods at me, starts rifling through the lottery tickets, like she’ll recognize a winner when she sees it. I try to go back to finishing my final civics paper.

Another kid walks in, also in a hoodie, brown this time. Avoids my gaze. Glances over at Red Hoodie, still checking out the cooler. Red Hoodie glances back.

La Paz leaps from her perch beside the detergent and strolls over to the old lady. Rubs against her leg.

“Hello, little precious!” she says to the little bitch. Bodega cats, always a hit with the punters, as Papi would say.

Brown Hoodie says: “Yo—you carry malt?” I stare at him. Brown Hoodie stares back.

I look over at Red Hoodie. He’s holding a knife, shining a crooked grin at me.

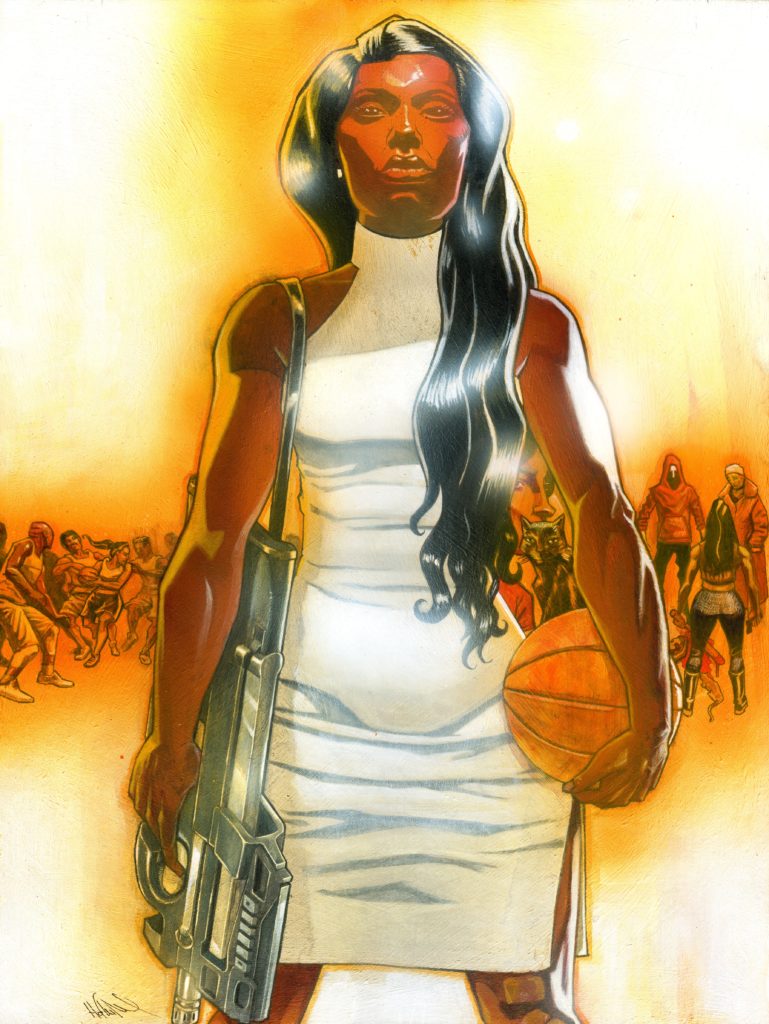

I look back at Brown Hoodie. Holding a gun on me. An expensive Heckler and Koch, clattering in his shaking hands. “Empty the fucking till, bitch,” he says.

There is a weird pause between the old woman seeing the gun in all its glory and the drawn out “AAGGGHHH!” that erupts from her.

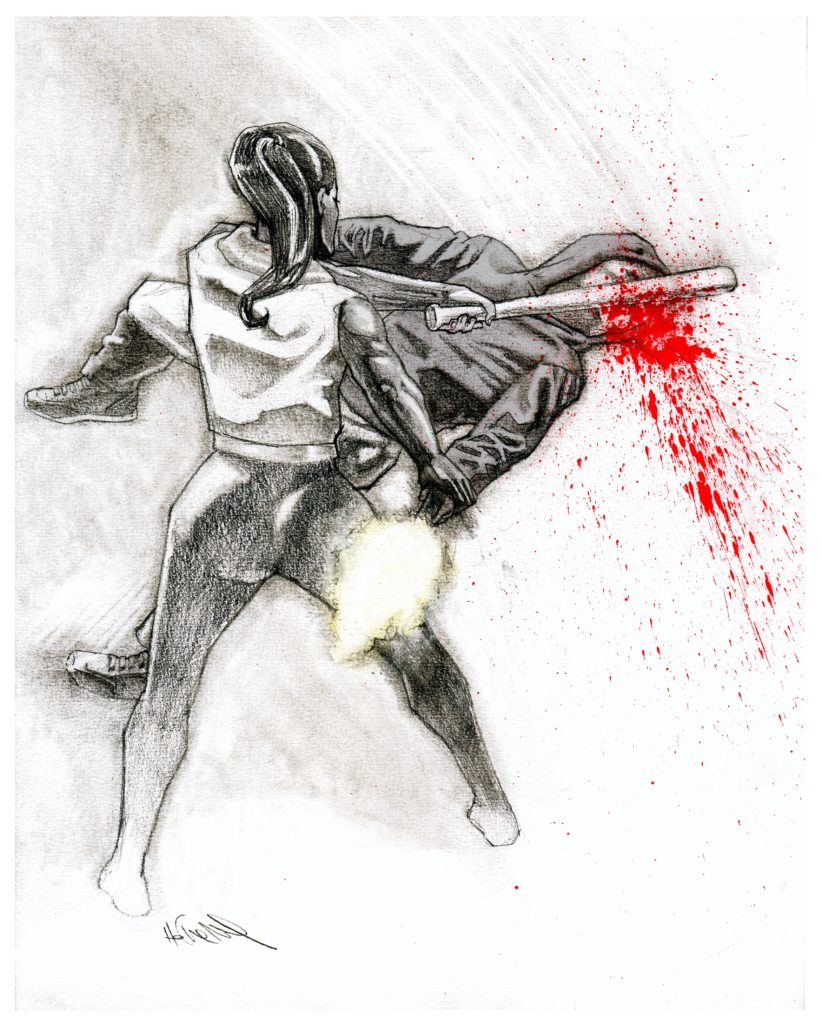

Maybe it just seems that way because I’m watching this all in slow motion. It’s happening outside me, like the last play with eight seconds left on the game clock and down by one. Maybe it’s because I’m sick of hill rats coming down to play gangsta among us gutter dwelling flats folks, knowing that all they gotta do is get out the door and they can hide behind a wall of lawyers and friendly cops, prosecutors, judges, all in thrall to daddy’s money. Maybe it’s  because just like in ball, you don’t steal from me, I steal from you. But my hand is reaching out and grabbing the gun and pulling it and his arm behind me before I even realize I’m doing it.

because just like in ball, you don’t steal from me, I steal from you. But my hand is reaching out and grabbing the gun and pulling it and his arm behind me before I even realize I’m doing it.

The gun fires, I feel the kick, my bones feel for a second like they’ve turned to powder, and still I don’t let go. At the same time, I’m pulling the aluminum bat out from behind the counter where we always keep it and—I’m positive—fracturing Brown Hoodie’s skull. I look down at him on the floor clutching his broken head, and there’s already a blood pool forming underneath it.

The old lady is screaming even louder now. La Paz starts licking up Brown Hoodie’s blood.

I look over at Red Hoodie. His eyes are saucers. I wonder absently what my eyes look like right then.

I walk out from behind the counter, holding the bloody bat. I’ve still got the gun in my hand, and probably I should point it at him, but in that moment, I forget I’m holding it.

Red Hoodie takes two steps back. “Yo, this—this was his idea,” he says, choking out the words. “OK,” I say, walking slowly toward him.

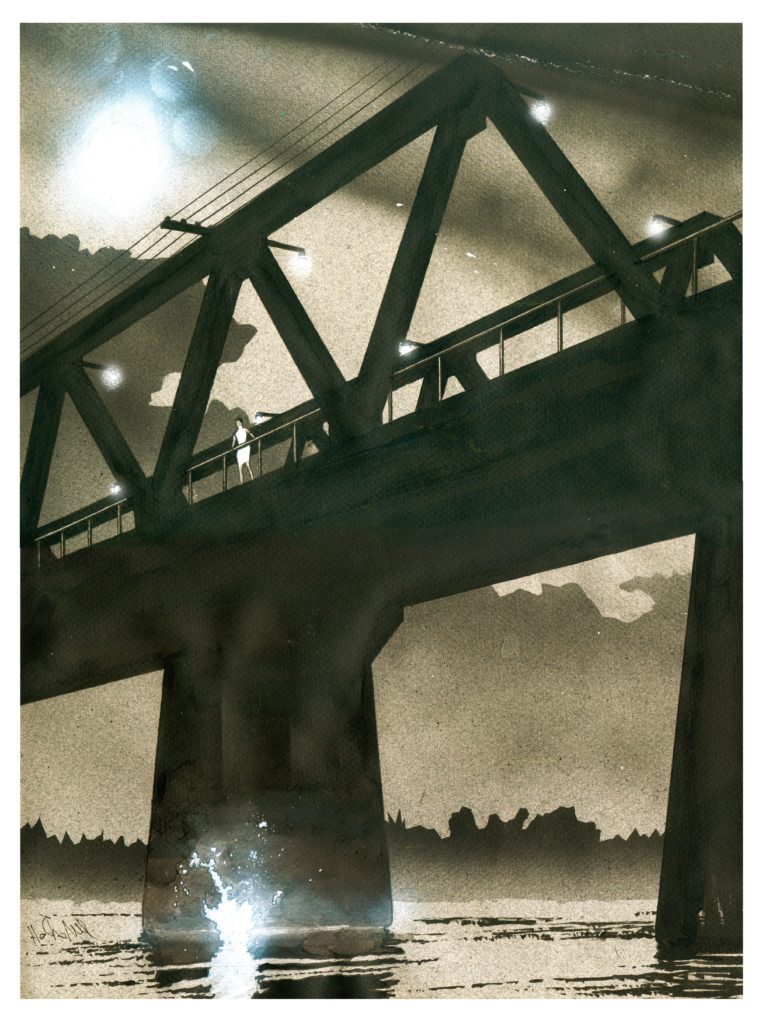

He looks at the weapons in my hands. Drops his knife. Turns and sprints out of the bodega, the place my mother and her parents built with their own hands, the place my father sweats and bleeds over daily, honoring her memory, honoring the neighborhood she swore to serve. I watch him go.

I look back at the old lady. She’s stopped screaming now. Instead, she’s looking at me with an expression I’ve never quite seen anyone look at me with before.

__________________________________