“When did you last see her, your mother?”

“Those days add up to too many.”

“That I understand,” I say, anxious for the days back to Ray to be too many to track.

“Here we are,” Earl says.

And then there it is just ahead of us, a wide plateau of land dotted with brown boulders that look like they’ve been dropped from the sky. Spruce trees sit on the edges of the plateau. On the far side, facing us, is a row of buildings that lean softly to the right as if they are putting all their exhausted weight into their one good hip.

Like the diner the buildings are aptly labeled: saloon, post office, grocery, church. They are painted garish yellows and ketchupy reds, although any paint job was clearly done some time ago. The beaten-down wood shows through, raw and indignant. The remnants of a truck, hood open, guts gone, sit sadly in the tall grass. A smattering of tree stumps in varying states of decay sit in the barren field between where we stand and the storefronts. A rusted chain saw tilts sadly against a skinny but still-standing pine. At the end of the row of buildings and separated from them by a distance of about thirty feet is a farmhouse. Simple in frame but tall and once proud. The roof is caved in, a great toothless hole gaping up at the sky.

“Nothing sadder than a roof given in, is there?” Earl asks.

“Tell me that’s not where you live.”

“No, ma’am. George fusses in there but I have a spot in the barn behind these buildings and down the hills that way.” He points toward the saloon. “You’ll love the barn. I’m fixing it up real good so a whole family could definitely live there.”

Closest to us there is a firepit full of ash and blackened objects that aren’t meant to burn (beer bottles, curling food wrappers, and cans). There are beer bottles strewn around the small open space. There is no sound. No birds, no crickets, no rustle of leaves. There isn’t even any undergrowth. Just dusty ground that looks to have been tamped down by anxious feet. A small dead space.

“So where is he?” I’ve got that uh-oh feeling in my stomach. That child-molester, kidnapper, razor-blade-in-the-candy feeling: Tell Mommy and Daddy about the bad man.

“Where’s who?” Earl asks. He is looking at me but that stupid mask makes it impossible to tell if he’s jok-ing. My eyes are tired and I’m out of breath.

“George, for fuck’s sake! Where is George?” I ask, and shiver. I zip up my jacket to my neck before crossing my arms over my chest to hug my breasts tight against my body.

“You scared?”

“No,” I say, and resist the urge to ask for my pills. I’ve been doing some kind of something since I was sixteen, when Ray and I decided to clean up the remnants of our parents’ Halloween party. Drinking, smoking, snorting.

My father made me swear I would never be like him, but he only made me swear when he was sober and miserable. When he was drunk, he was happy, unafraid of the world and its consequences.

With beer or weed or speed in my system, I felt joy. It made the hate inside me shrink down. And I could forget my promise. Dad wanted me to be happy, bold, and brave. It didn’t matter how I got there.

The hospital kindly turned me over to prescription drugs and life happens at arm’s length now—close enough to destroy the joy and distanced enough to fog the pain. My body off of everything will be an unfamiliar landscape.

“Sometimes it’s safer to be scared. That’s what Mama says.”“Sometimes it’s safer to be scared. That’s what Mama says.”

Maybe, I think but do not say. Maybe feeling all of it every moment will be safer.

Something in me shifts. Something that I thought they removed months ago opens up and I reach for him. To hug him? To shield him? My arms think better of it and drop back to my sides before I notice that he has taken a step toward me as if he knew my offer of comfort was coming before I did.

“Show me,” I say.

Earl nods and leads me around the dead campfire toward the farmhouse. For a minute, I assume we are entering the building, but he lets his shoulder brush against it silently as we walk. He disappears around the corner. I pause, stand up straighter, and then step forward. There’s a big man slumped in a beat-up lawn chair. His back is to me and his head is rolled slightly to one side.

Earl stops. I take a few more steps forward. I look over my shoulder at Earl, who gives me a nod.

“Hello?” The man, George, doesn’t answer. I catch the smell of him as a breeze moves through. Something is wrong. Urine. Sweat. Alcohol. A darker smell too. Decay. “What’s wrong with him?” I ask Earl.

“Nothing wrong with him, but I wouldn’t wake him if I were you.”

“Why not?” I whisper back. All the hairs on my neck are standing up.

“I’ll be right back,” Earl says in a quick whisper. I spin on my heels in time to see him disappear around the building.

“Goddamn it, Earl,” I say, and think about following, but my legs are shaking.

George is wearing a black leather jacket and a black knit hat. I can’t see much about his size or anything of his hair. He is just a big, sloppy body in a chair. From the back George could be anyone. Could be my dad. Could be Lowell. Could be Ray. Could be me.

“Do you need help?” I ask, and take a step toward the body. “Listen, your kid said you’d be able to give me gas. My van ran out. That’s all I need, then I’m gone.”

As I come up beside him, I have to cover my mouth and nose. The smell is strong. The hat is a ski mask. His face is invisible. Just eyes through the holes and they are open wide, a too-clear blue as if bleached out by the sky. He has on ripped jeans, which are wet from the crotch to his knees. His blue sweatshirt is slightly wet down the front. Vomit. There are beer bottles all around him. Too many to drink in one sitting. His wide eyes stare up at the tops of the trees or the sky, I can’t tell which. I turn to see what he sees and two crows circle. Then a third joins and a fourth. They glide, making no noise. Their beaks sharp and ready.

“You drunk?” I study his face. He’s not present, and from the looks of things, he might never even know I’ve been on his property. “You dead, mister?” I hadn’t planned to say that word, “dead,” but there it is floating around now and suddenly I know it is the obvious choice. I move toward him slowly, unsure of what I’m planning to do, but feeling sure I have to prove to myself that he isn’t dead so I can leave both drunk man and small boy behind. I get close enough to reach out and tap his shoulder with two fingers. I keep my other hand clamped over my mouth and nose. No response.

I give his muddy cowboy boot a kick. Nothing.

“I wouldn’t wake him up if I were you,” Earl says. He’s back and standing right behind me.

“God, you’re a creeper. Stop sneaking up on me. If I didn’t know better, I’d say this man was dead. As a matter a fact, I don’t know better. He’s dead. This is fucked-up.”

“He’s not dead. He’s nappin’.”

“Does he always nap with his eyes open?”

“Usually does. Yep.”

“That’s fucking creepy.”

“He’s just sleepin’ it off.”

“Earl, honey, he is not sleeping. Something is wrong.”

“It’s the white powder I gave him.”

“You poisoned him?”

“It kills the rats.”

I wish I could see Earl’s face behind the mask. As it is, I can’t tell if he’s smiling or frowning and the mask has regained its glare, its crow-attracting shine. I’m close enough to him to see the hills and valleys of the tinfoil crinkles and it looks like the surface of the moon.

“Earl, I hope he’s a son of a bitch.”

“He’s just nappin’, ” Earl whispers.

“How long has he been napping?”

“Since yesterday noon. I gave him some of your medicine this morning.”

“How much?”

“Many of them.”

“That’s not a number.”

“All?”

“Is he still breathing?”

“Yes, watch.”

We stand quietly waiting until George’s chest rises ever so slightly.

“I guess that was a breath. If he’s alive, you have to get him to a doctor, and really, it strikes me as a very bad habit to be poisoning people so early in life. Just look at him. We need to call someone. I mean, you need to call someone.”

“There isn’t a phone here.”

“You need to get him help before this turns into some-thing even bigger than you want. Believe me. I know. Some choices can’t be undone.”

Earl is quiet for a moment, thoughtful, but then he speaks with a sadness that seems deliberate: “I was hoping you’d help me bury him.”

__________________________________

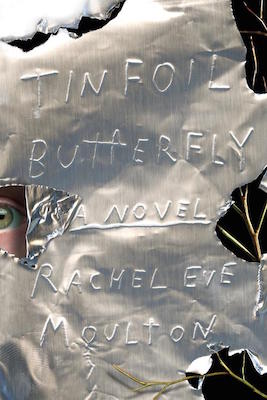

From Tinfoil Butterfly, by Rachel Eve Moulton. Used with the permission of the publisher, MCD. Copyright © 2019 by Rachel Eve Moulton.