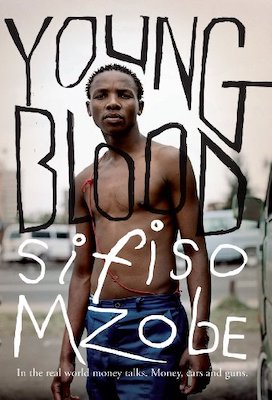

Young Man, It Starts Here

Almost all the people I called my peers were second-generation township dwellers. When my father said he was going home, he embarked on an exhausting, bumpy drive to the rural south coast, past Umzumbe and beyond, to dusty villages where youths still greeted elders. I went there too from time to time. There was nothing lavish about the place. When I said I was going home, I meant Umlazi—a township. Both my maternal and paternal grandparents were of the last generation that lived in the same place for their whole lives. Times changed fast. Even I, bush mechanic that I was, vowed not to die in a township, let alone in my father’s house. My father had been a hustler in his past life. Brave and wild. He may not have shown it, but I knew he was proud when he saw me make money. Even in our backyard, Dad always passed customers on to me and let me keep the money. That morning, he was focused on fine-tuning an engine. The hum of the Ford Courier may have sounded perfect to other ears, but with Dad it was paramount that every car pass the coffee-cup test before he proclaimed his work done. Ma told me he used to drink and smoke back in the day, but when I was born coffee replaced liquor and cigarettes. My father drank a minimum of ten cups of coffee a day. Through the spring, summer, autumn and winter, he sipped hot coffee from his giant, ageless enamel cup.

It was the same cup he used for his test. If the job was engine-related, Dad filled the cup with water and placed it over the cylinder-head cover of the tuned engine. If the vibrations did not spill the water over the rim of the cup, the job was proclaimed perfect. A spill meant he started all over again.

I related with my father on a comfortable, balanced level. Casual, but with respect. He treated me as if I used my brain. For that alone I would always defend him. When his friends came to get their cars fixed and he was not there, they told me stories about his past. The theme was always bravery and speed. I knew I had inherited speed from him, judging by all the goals I scored on the soccer pitch. Bravery I was yet to find out.

Each township has its own type of hustle. In KwaMashu, it is strictly robbery. In Chesterville, they have perfected the art of housebreaking. You buy the latest in home entertainment in Chesterville, at prices lower than low. In my township, Umlazi, we steal cars at such a rate that the flying squad—fly as they do— can never keep up.

“I know you are growing now.”

We were in the Ford Courier, road-testing it. Not a drop of water had spilled during the coffee-cup test. I had been inside many cars—some turbo-charged, some with mind-blowing conversions. Different drivers too, but none of them handled a car like my father. He did not just drive the car, he tamed it, so that he could do whatever he wanted with it. Gears were changed with impeccable timing. When he had a manual-transmission Toyota Cressida—I was about ten—Dad changed gears so perfectly that the neighbors thought the transmission was automatic.

“And your generation is the fastest growing the ancestors have ever seen.”

I liked it when my father spoke. His were words from a mind that sifts out all excess thoughts.

“You left school. I don’t agree with your decision, but I see why you came to your conclusion. The world outside school is the real world. What I am about to tell you now I will never repeat again. Are you listening?”

“Yes, Dad,” I said.

“You are now in the real world. In the real world, money matters. Notes are the tiny hands that spin this world around. The more of these tiny hands you have, the better your life will be. In this real world, you focus on what you want and go hard for it. You see school as an avenue to nowhere, but there are other ways to profit as well. Use your talents to gain. But you see this…”

Dad pulled his overall by the collar to reveal his tattooed shoulders. He looked straight into my eyes with regret all over his face.

“My boy, this is a man-made fairy tale. Don’t believe in it. Whatever avenue you choose, don’t make the mistake of taking this fairy tale to heart, or anything that will limit your thoughts. Boy, in this world you are born alone. Remember that. For every step you take, make sure you gauge your gain. Measure exactly how that step will help you. Life is progress, my boy. But for whatever you do, my son, put muthi first. For protection.”

I had learned over the years not to interrupt him. “What do you think goes on in the night? You think you roam the streets alone? As you walk, bad spirits are on your left and right, back and front.”

I knew what would follow. And it did.

“You are going nowhere today. I have already arranged with old man Mbatha. He is expecting us.”

From as far back in my seventeen years as scientists say memory begins, I had known old man Mbatha. He was our family’s traditional healer. Despite what people will say, most township families have one. When doctors and their medicines failed, we went to old man Mbatha. With him it was always from the ground—trees and natural concoctions. The old man cured everything, from headaches to illnesses cosmic and emotional. Once, when Nu was five and had stopped talking, old man Mbatha cured her. He burned so much incense that Nu removed her thumb and coughed.

“It smells bad,” she said, causing my mother to burst into a mixture of prayer and ululation.

“You are great, God,” came from my mother’s mouth, along with sweat from her brow and tears from her eyes.

“The child is only half cured,” old man Mbatha said. “Your ancestors do not ask for much. Slaughter a goat, make sorghum beer.”

It turned out to be a big party. My father got money from somewhere. The ancestors ate and drank a lot.

I had been to old man Mbatha’s White Room three times in my life. The first time was when Nu regained the power of speech. The second time was after my car accident. Both times I took old man Mbatha’s antics for granted. It was all like a big joke. All through those two visits I fought hard to contain my laughter. I did not believe that anyone could speak to the ancestors. That, in turn, made my father so angry he did not speak to me for two days straight.

The third time I was in the White Room, however, turned me into a true believer. Maybe the somber nature of my visit encouraged me to believe. I was at the lowest point in my life. When I was sixteen and a half, another soul departed from this world by my hand.

__________________________________