Acid has had a long and colorful—way too colorful!—relationship with crime fiction.

LSD or lysergic acid diethylamide was first synthesized by Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman in the pre-fabulous year of 1938, but almost as soon as Sandoz Labs introduced the stuff as a psychiatric tool ten years later, the chemical compound started making surprise cameos in detective fiction.

Why is that?

Well, for one, LSD was itself mysterious—this microscopic drop could blow open your mind and send you to infinity inside an hour. Also, for a multitude of reasons, some solid, some hysterical, LSD came equipped with a fear factor. Long before the counterculture got their hands on it, the CIA and other orgs started administering acid tests to military personnel, government agents, prostitutes, mentally ill patients, and random Joe and Jane Citizens, sometimes without the subject’s slightest inkling of what kaleidoscopic Escherian maze they were about to get lost in.

But there’s a third reason why crime writers gravitated toward psychedelia, maybe the most important reason—it’s a detective’s job to get drugged, smacked around, bonked on the head, and sent down a nightmare spiral toward the truth. For mystery writers of every stripe, LSD was simply irresistible. The crazy sugarcube had it all—shock, color, dramatic freakouts, danger, reality vs. fantasy, and the sense that nothing was ever what it seemed.

Here is just a microdose of the mystery tale’s long and strange trip.

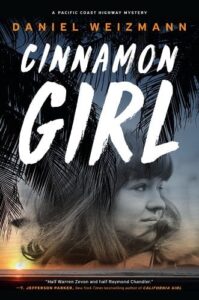

M.E. Chaber, The Splintered Man

Some claim that pulp masterpiece The Splintered Man (1955) by M.E. Chaber (real name Kendell Foster Crossen) is the first fictional appearance of LSD in crime fiction—where it’s used as nothing less than a Nazi weapon of mind control! Supersleuth Milo March, ordered back into active duty, learns he is to kidnap a recent defector from the East Germans. One subway ride later, March hooks up with a Frau Fatale, blows his cover, and gets handed over to an ex-SS running high-dose acid experiments—talk about a bad trip!

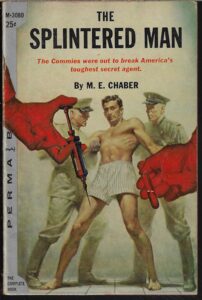

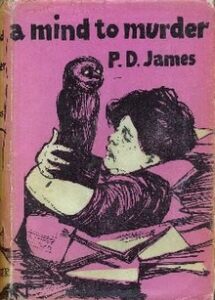

P.D. James, A Mind to Murder

Interesting then that just eight years later, in PD James’s second and arguably best Adam Dalgliesh mystery A Mind to Murder (1963), LSD is presented as something less than the liquid menace. Here it’s being used to treat patients in a British outpatient psych hospital—right alongside shock therapy and art therapy. With characteristic deference, James is even-keeled about this newfangled psych tool. “It’s a remarkable drug…the patient is flushed and restless and quite withdrawn from reality.” Quite!

John D. MacDonald, Nightmare in Pink

Cut to John D. MacDonald’s Nightmare in Pink (1964)— the second in a high stack of Travis McGee classics. “One drop of a tasteless, odorless substance can turn you into something they come after with a net,” Trav warns as he’s coming on to Dr. Daska’s private variation, the dreaded Daska-15, an LSD compound that gives “consistently ugly hallucinations.” For hardboiled McGee, the ride is even rougher than expected. “I bought a paper. The stairs tilted sideways. The railing felt like a wet snake. I shoved seven keys at seven keyholes and they all fitted and all turned, and I stumbled into a pink room and curled up on the bed, my knees against my chest…have a cup of nightmare.”

Riot on the Sunset Strip (1967)

It was just a matter of months before the still-legal LSD hit the teenybopper circuit like an atom bomb, allegedly sending some of them jumping off roofs in the hopes that they might fly. Teensploitation flicks like American International’s Riot on the Sunset Strip (1967) were quick to pick up the sin-sational crime element. The movie is about a troubled young daughter of a cop who doses just to be “one of the gang” and ends up the victim of gang rape.

Dragnet, “The LSD Story”

That same year, the Hardboiled Cops Meet Trippin’ Teens Genre reached its zenith in what might be Dragnet’s most famous episode, “The LSD Story”, written by Jack Webb himself under the pen name John Randolph. When Joe Friday and Bill Gannon work the MacArthur Park beat, they discover a face-painted freak named Blue Boy with his head in the sand—like, literally. They yank him out and shake down his pocketful of sugarcubes as he rants about “Reality, man, reality! I could see the center of the earth! Purple flame down there with a pilot light!” Needless to say, the story you saw was true. The names were changed to protect the innocent.

By the time Helter Skelter was published in 1974—featuring the terrifying Hawaiian Hamburger from Hell incident—LSD and murder had become, unfortunately, a matter for True Crime. Vincent Bugliosi’s paperback won the Edgar Award that year and, for a time, seemed to be the most ubiquitous bedside object in America.

Overtime, though, as nightmares faded and our understanding of LSD began to expand, mystery writers started approaching the topic with greater sensitivity and finesse.

James Lee Burke, In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead

The unspeakably great James Lee Burke’s In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead (1993), sixth title in the magnificent Dave Robicheaux series, finds our hero-detective drinking a stiff one spiked with acid, but instead of freaking out and jumping off a roof, he ends up in fantasy conversation with the phantom of Confederate General Hood and the soldiers under his command. Incredibly, the hallucinated General gives trippin’ Robicheaux good advice about how to solve the case!

T. Jefferson Parker, California Girl

T. Jefferson Parker’s California Girl (2004), my personal fave of his many masterpieces, looks back on Orange County ‘68 when the discovery of a decapitated young woman leads to a rogue’s gallery of culty hippies, Vietnam vets, gonzo reporters, and Timothy Leary and Dick Nixon themselves. In one of the most memorable scenes, Investigator Nick Becker, working his first case as lead detective with the county sheriff’s department, takes an accidental dose of Orange Sunshine, goes home in a daze and makes tender love to his wife through the afternoon before collapsing in a vision of purple tulips, red Ford Country Squire station wagons with simulated wood-frame paneling, blue fire hydrants, and a thousand images of the dead girl’s speaking but disembodied head.

The LSD-laced mystery, it seems, has finally grown up.

****