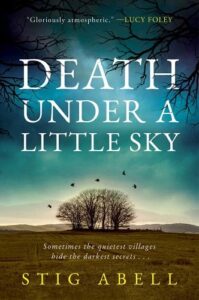

There is a magnificent bit in a Sherlock Holmes story, which—subconsciously in the beginning, I guess – gave me the inspiration for my first detective novel, Death Under a Little Sky. Holmes and Watson, that charming odd couple of nineteenth century fiction, are on a train, chewing over the details of some seemingly baffling case, when they get to talking about the landscape that speeds past outside their window. Watson is, typically, conventional in his regard for its beauty; Holmes is, typically, caustic, in his response, noting that no dark and smog-soaked rookery is more likely to present “a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside”. He goes on, as he so often does, to accentuate his argument:

Look at these lonely houses, each in its own fields, filled for the most part with poor ignorant folk who know little of the law. Think of the deeds of hellish cruelty, the hidden wickedness which may go on, year in, year out, in such places, and none the wiser.

In the British countryside, nobody can hear you scream. It’s an arresting notion, and one that worked its way into my mind, insidious, waiting for its moment to flower into an entire fictional setting.

I never fail to marvel that Arthur Conan-Doyle managed effectively both to invent the genre of crime fiction and perfect it all at the same time, just as the Victorian period was meandering to its conclusion and the twentieth century was establishing itself. You can perhaps make an argument for Dickens in Bleak House, or his friend Wilkie Collins, give a respectful nod maybe to Edgar Allen Poe, but finally you must accept this: every detective book in the Western canon, for the next hundred and forty years or so, exists because of the puzzling, rewarding tales of an opium-addicted show-off, and his lumbering, blundering Boswell.

The Golden Age that followed soon after further embedded the attractive concept of bloody crime and bloody-minded resolution. In England, strikingly, the chief practitioners of detective fiction were women: Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh. Perhaps only the first two are popular now, and perhaps only Agatha Christie truly survives in the brutal battle to linger in our otherwise amnesiac social memory. Sayers was the more brilliant writer, I think, the more fascinating woman, and her books about the relationship between Peter Wimsey and Harriet Vane (the erstwhile murder suspect in Strong Poison) are the more satisfying to linger upon and re-read.

It is odd that we call the genre both “crime fiction” and “detective fiction”. In fact, in this germinal stage, we might recognize that the detective is almost always more important than the criminal. Thus, those four authors are still known because of how well we know their bloodhound creations: Poirot and Marple, Wimsey, Campion, and Alleyn. We admire the characters’ foibles and mannerisms; we marvel at their superhuman powers of deduction. We are all besotted Watsons, when it comes right down to it, scratching our bewildered heads in bovine wonder at someone more intelligent than we are.

Meanwhile, in America, the genre was branching off into a different direction: more masculine, violent, hard-boiled, urban. We got Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, the concept of the rugged loner, booze-soaked and brutalised: “down these mean streets a man must go”, said Chandler, “who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero, he is everything”. That hero—mostly male, but less so in recent years—has been with us, in books and TV and film, ever since.

But an anatomy of such creative largess, a pedantic charting of each evolution and development, is ultimately an odious thing. Why try to enumerate every twist and turn of the genre’s history? Its brilliance is there in its very generosity, its ability to shift into different settings and cultures and countries. Think of where you can go if you confine yourself solely to stories about someone solving a crime: ancient Rome, with the charming, tousled-head Falco as imagined by Lindsey Davis; the green fields and trickling brooks of medieval Shrewsbury thanks to Ellis Peters; Inspector Montalbano’s fridge and its reheatable Sicilian cuisine; Ian Rankin’s Edinburgh; Michael Connelly’s Los Angeles; the strange underworld of Fred Vargas’s Paris; and on and on. If you were to read a detective book a week for the rest of your life, you would never run out of places in which to lose yourself. And, even after years of reading, you would probably still fail to spot the quiet-voiced, fifth-most-important character whom you don’t meet properly until the middle chapters, and who turns out to be the killer.

So why did I feel I had to add my own worldly-wise detective, my own defined landscape, to this never-ending list? A good question, of course, and one I’ll come back to. But—this will turn out to be pertinent—why do I, why do we, love these books in the first place?

My theory is a simple one. We live in a world—increasingly so—of mess and superfluity and interminable distraction. Our work and our home lives bleed together in infuriating, inexorable fashion. We are prisoners of the never-ending now. Someone said to me the other day this piece of devastating mordancy: “today is the slowest day of the rest of your life”. Everything gets quicker, more restless and relentless, and has since the day you were born. Detective fiction, in contradistinction, has shape, offers an answer; it concludes. The basic premise of all these stories is that something will go wrong, and then it will be explained, answered, put right.

I don’t know about you, but I have always sought to find peace in fiction. At various points in my life, I have suffered from a sort of mental unease, gnawing anxiety, a sense of proximity to panic. I have found solace against my uncertainty in the certainty of books, especially detective books, relying upon their ability to provide me with resolution in an otherwise irresolute existence. I owe—in a real sense—my sanity to them.

That did not mean I necessarily believed I would be able to add my own novel to the culture’s tottering and limitless stack. But one day, during the Covid pandemic, I started writing a story of a man whose world was wobbling, and who needed a fresh start, who wanted to escape the drudgery of the city and find some peace and repose in the “smiling and beautiful countryside”. He is an ex-policeman, Jake Jackson, and he inherits a place called Little Sky, in the middle of nowhere, beautiful and desolate, so far from civilisation that phones and the internet do not work. At the time I was locked down in a house with three children, so you can probably understand why the concept was so appealing.

Little Sky is both deeply desirable—Jake has his own lake to swim in each morning—and deeply, sometimes frighteningly isolated. It is Sherlock Holmes’s warning made real. And Jake gets dragged into a mystery (of course he does) soon after he moves in, when bones are discovered that might link back to a death of a young immigrant woman some years before.

I quickly realized that my embracing of the concept of isolation—which interested me anyway—meant I didn’t need to burden the narrative with any technology at all: Jake was uncontactable, and had no other means of learning what had happened than by walking and talking to people. We were back in the Golden Age, except he didn’t—unlike Poirot— even have a telephone. When he gets to know Livia, a local vet, they can only communicate by leaving bits of coloured cloth on a designated tree. A relationship develops from there.

Detective fiction can be romantic, you see. After all, Dorothy Sayers’s novels are a long love story between Wimsey and Vane. Holmes and Watson love each other really, too. And I wanted my books to be mysterious and eerie, but also slightly sentimental as well. I want people to want to come back to Little Sky more than once.

That’s another important point, and a good one to finish on. I honestly believe that one of the truest pleasures in life is discovering not just a book to love, but an entire set of them. My favourite fiction is, in the end, series fiction. I don’t just want a fleeting encounter with an important character, I want to get to know them, to have them as part of my life, whether it be Bosch or Morse or Cadfael or Brennan or Travis McGee or Miss Marple or Kinsey Millhone or whoever. Detective fiction at its best is something familiar, something personal, something reassuring. Anyway, Jake Jackson is sticking around for at least three more books, and that makes me very happy indeed.

***