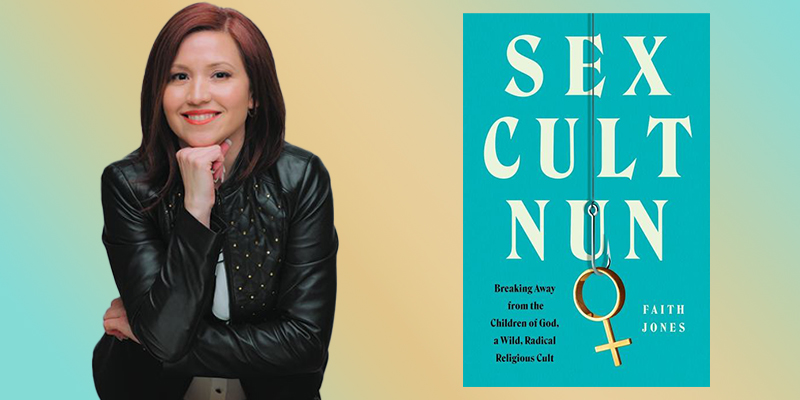

Faith Jones has had a challenging life. She was born into the Children of God cult, left in her early 20s, and later, reconnected with her family after they, too, left the cult. Her new memoir, Sex Cult Nun, is clear-sighted and inspiring; she doesn’t need to forget the past to move beyond it, and that’s an amazing lesson for our amnesia-challenged society. I asked Faith a few questions over email to go along with the publication of her new book.

Molly Odintz: The story of a cult seems to be, in some ways, the story of domestic violence writ large—do you find the same parallels?

Molly Odintz: The story of a cult seems to be, in some ways, the story of domestic violence writ large—do you find the same parallels?

Faith Jones: Yes. Domestic violence involves stripping away boundaries and using manipulation and fear, often combined with love bombing, for control. In domestic violence and child abuse, the abuser often sees the other person as an extension of themselves or their property. The abuser believes they have a right over the victim—to treat them in a certain way. There is also an element of, “this is for your own good.” The critical element of control is the systematic destruction of boundaries and any sense the victim has of self-ownership and personal rights. If you don’t belong to yourself, then what right do you have to object? What people get wrong about cults is that they all start out like families. People don’t walk out their front door looking for an abusive cult to join. They are looking for family, belonging, and purpose. That’s what cults provide, but in the process, they take away self-ownership, free thought, and independence through manipulation and often abuse. Sounds like a domestic violence situation, doesn’t it?

MO: This memoir is not a crime story, but it is full of crimes, committed against the vulnerable and the young. What were the mechanisms that allowed the Children of God to exploit and harm its own members?

FJ: The Children of God convinced members they did not own themselves, that they belonged to God or the group. By taking away the members sense of self-ownership, the leaders also stripped them of a sense of independent moral responsibility. If people did what they were told, they were following “God’s will,” so were not responsible for any wrongdoing. The leaders couldn’t be wrong. Blindly following a leader, without fostering independent questioning is where most cult-like groups go wrong. But most importantly, the leaders didn’t have an objective standard of ethics to measure all “revelations” against.

MO: As a follow up, what do we need to do to protect the young and marginalized from being vulnerable to exploitation to begin with?

FJ: Teach them the Ten Golden Principles of Integrity or Conduct. It’s a simple, objective standard that encompasses the basics of ethics beginning with our first right—our right of self-ownership. If young and marginalized people have these embedded in their psyche, it will be much harder to deceive them. Teach parents these principles as well, so they don’t unwittingly raise children who are susceptible to violators. Many of modern society’s norms and institutions, including the traditional education system with its focus on giving children the answer and expecting them to memorize and regurgitate it for an “A”, create people who are addicted to authority—looking for someone to tell them what to do, believe, wear, and like. Instead, we must focus on teaching critical thinking. In my work as an educator and activist, I’ve seen this framework give people the language to describe a violation, to articulate their rights and stand up for themselves. It is much harder to take advantage of someone who is armed against the abuser.

MO: How did you find the strength to break free, and what advice would you pass on to those who are seeking to extricate themselves from similar situations?

FJ: I refused to be unhappy, and I was willing to do whatever it took to not end up bitter. I had a goal—to go to college. With each obstacle, I stayed focused on the goal and adjusted. I had no idea I would be where I am today. I just took it day by day and did the best that I could at each task in front of me. One thing I know, you are for sure smarter and more capable than you think. So, first, take back your power by claiming responsibility for your life and happiness. It’s yours. No one else can own you or has any right to tell you what to do, not your parents (if you’re over 18) or your spouse or religious leader. There is help available—shelters, centers, scholarships—once you make the decision. In the last few chapters of my memoir, I share the principles I discovered that help someone spot and clearly articulate even the most deceptive abuses. I’ve also created free resources available on my website. If you’re willing to do the work, healing, happiness, and freedom are possible.

MO: Your memoir has so much sympathy and understanding for your parents, trapped as they were. How did your family come to reconciliation?

A: My dad was basically born into the cult, pulled out of school by his father at twelve, and my mother joined when she was barely twenty-one. They were products of the society they came out of and the group environment they submitted to. It doesn’t excuse the violations; but I understand. People can think their behavior is godly and loving, but because they believe a lie, they act in a way that is abusive.

At a young age, I saw my parents as fallible humans rather than idealized parents. It took time after they left the cult to recognize the error of their beliefs and apologize to me and my siblings. I appreciated it, but I wasn’t waiting for that apology to heal. I knew my happiness and success was up to me, so I could afford to let them come to the realization in their own time.

MO: Why are we as a society so fascinated by cults? Does this fascination harm or help those who manage to free themselves from cults?

FJ: I think we are fascinated because we want to understand how people could do such a thing, and is there a danger, if given the right circumstances, that they themselves might succumb?

I think the stigma that cults have can make it harder for those trying to integrate into society. When I left the Children of God, I didn’t tell anyone that I’d been in it. I didn’t want to be seen as a “poor cult kid” but as the strong, capable, smart woman I was working to become. It also felt impossible to explain to people what such an upbringing was like. I hope that my book will help demystify this group. And, most importantly, show people who are coming out of cults that they can make it and create a good life, that they can heal.

MO: Of all the fictional depictions of cults that have popped up recently, do any of them feel emotionally true to your experiences?

FJ: I related to the Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and her humorous mishaps trying to navigate reentry into society. There were a few scenes in The Handmaid’s Tale, like the birth scene, that were strangely familiar. But I think fiction often over-dramatizes the strange and the bad, which makes it seem unrelatable for me.

***