In interviews and at writers’ events, there are certain questions that you can rely on to come up again and again. How long does it take you to write a novel? Do you have a writing schedule and if so what is it? Which writers inspire you? And always, sooner or later, where do your ideas come from?

The first three are a breeze. Two to three years, give or take. Yes, once I’m into the writing stage of a novel I go straight to my desk after breakfast and try not to leave it again until I’ve written a thousand words. An ever-evolving roster of brilliant writers which invariably includes George Eliot, Virginia Woolf, Alice Munro and Hilary Mantel.

It is only the last question that gives me pause. In part, I think, this is down to a kind of superstition, fear even. The truth is that, though In the Full Light of the Sun is my sixth novel, I am still reluctant to examine how characters and stories form inside me, how they are nourished and grow until they are as real to me as my own family. Realer, perhaps, because how many of us really know just what our partners or sisters or friends are thinking as they perform their private, unobserved rituals or where they go in their heads when they are sitting silently beside us in the car? There is a kind of secret magic there, on the good days anyway, and I am afraid that if, in a quest for understanding, I attempt to dissect it, I will cut through something essential and destroy it forever. It is easier to explain it as a kind of faith: I do not understand exactly what it is that happens during the making of a novel but I know it has happened before and I trust that, as long as I am patient and go on turning up, it will happen again.

* * *

Subject matter, thankfully, is an altogether more rational beast. All six of my novels have taken particular historical moments or events as their starting point. It would doubtless have made my—and my publisher’s—life simpler if I had chosen a single seam of history from which to mine my stories, the Victorians, say, or the Tudors, but I am a magpie, easily seduced by shiny new things, and over the years I have snatched up all manner of glittering scraps from which to make my books: the scavenging toshers who occupied the underworld of the London sewers; the 18th century “casket girls” who were dispatched from France to a Louisiana colony three thousand miles way with their trousseaux in their trunks to marry men they had never met; the wife of a notorious Victorian politician who pretended all her life to be an heiress from Chile when in fact she was the daughter of a Yorkshire surgeon who had run away to London aged 15 to be an actress. But while these ideas may seem superficially unconnected, in each case I found myself caught by the same question, a question I had to which only grew more insistent the more I read: what would it have been like to have been that person, to have lived that life?

The story of the madman genius who never sold a painting in his lifetime, cut off his ear and shot himself is compelling. It is also, for the most part, untrue.I began researching In the Full Light of the Sun because I was fascinated by the pervasive myth of van Gogh, perhaps the only artist in history whose biography is familiar to those who know little or nothing about art. The story of the madman genius who never sold a painting in his lifetime, cut off his ear and shot himself is compelling. It is also, for the most part, untrue. Its origins lie instead in a colorful biography by a German art critic who shamelessly filled in the gaps in the story “to further,” as he explained afterwards, “the creation of legend. For there is nothing we need more than new symbols, legends of the humanity that comes from our own loins.” The book was a runaway bestseller. In Germany in particular, a nation reeling from devastating defeat in World War I, the story of a spurned and tormented hero whose genius was recognized too late struck a powerful chord. They co-opted van Gogh as one of their own: in the 1920s there were more van Gogh paintings in Germany than in the rest of the world put together.

As a storyteller this fascinated me. In recent years we have become used to the idea of “fake news” but stories have always taken shape according to what we need from them, because we are angry or jealous or eaten up with longing, because they suit us better that way. I knew I wanted to write about it but how and through whose eyes?

It was when I stumbled on the little-known story of Otto Wacker that I knew I had found the heart of my novel. Wacker was a young, handsome German dancer-turned-art-dealer who, between 1924 and 1926, came into possession of more than thirty previously unseen van Goghs. He refused to disclose the identity of the collector who owned them, saying only that he was a Russian prince forced to flee Moscow after the 1917 revolution. Instead, to compensate for their lack of provenance, Wacker asked experts in Germany and beyond to authenticate his paintings and guarantee their veracity. By then van Gogh was already one of the most sought-after artists of the modern era and, duly rubber-stamped, the paintings sold fast and for ever-increasing sums to dealers and collectors across Europe and the United States. Wacker gained a reputation for humility and straight dealing. He opened a gallery on Viktoriastrasse, Berlin’s grandest street. It was not until early 1928 that a Berlin gallery raised questions about four of Wacker’s paintings. By 1933, when the case finally reached court, all thirty two stood accused of being fakes.

* * *

These days there is not a single expert who is willing to speak out in defense of Wacker’s van Goghs. Looking at the grainy black and white reproductions that remain, it is hard to imagine how they could have deceived anyone. But van Gogh was, as one eminent critic admitted, “a painter of weak moments” and, for many, the desire to believe was very strong. At Wacker’s trial the expert witnesses disagreed violently about almost every canvas and the prosecution failed to build a convincing case against him. While Wacker was found guilty of fraud and accounting irregularities, the judges concluded that only eleven of his paintings could definitively be condemned as forgeries. Many were withheld by their owners and never appeared in court, leaving their provenance open. Wacker’s Self-Portrait at an Easel, purchased in New York by the American industrialist and art collector Chester Dale and praised by the New York Times as “considered by many the best thing he ever did,” hung in the National Gallery of Art in Washington until it was quietly decommissioned in 1984.

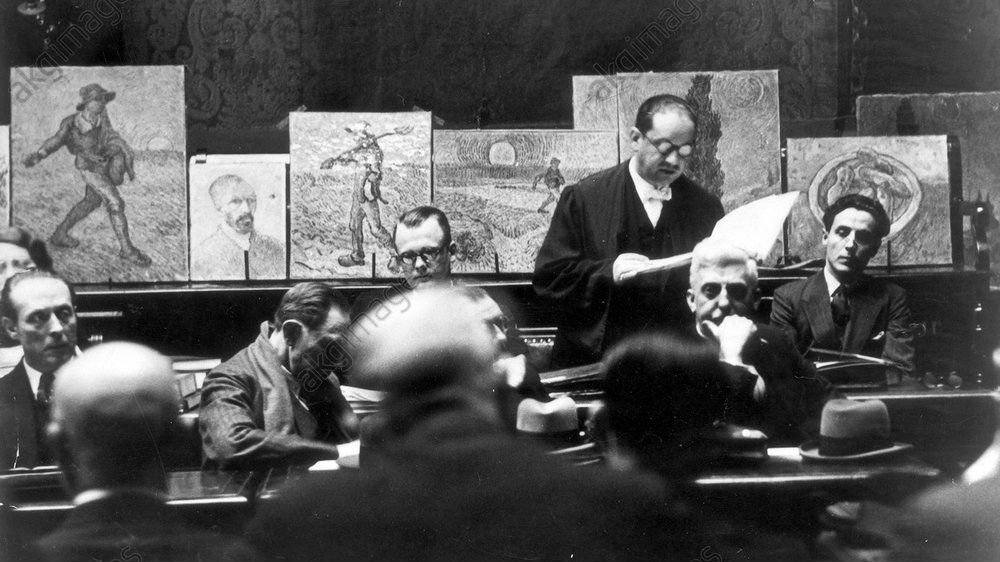

Otto Wacker on trial, 1932.

Otto Wacker on trial, 1932.

Why do people fake paintings? Is the motivation profit, vanity, revenge? And why do we care so much? Why is a painting that was worth millions of dollars suddenly without value because it was painted by someone else? Wacker’s story not only set me to thinking about these questions, it opened a world of characters caught up in his deceptions and their own: the eminent critic who loves paintings more than people; the talented art student who struggles to find her voice as an artist and a woman; the Jewish lawyer whose life and liberty is slowly and relentlessly being eroded by the Nazis. What would it be like, I found myself asking for the sixth time, to walk in those people’s shoes?

Most of my characters have no real-life counterpart and I have not cleaved to the historical record, in so far as there is one. I have altered and invented at will.The book that grew from that seed is very much a work of fiction. Matthias Rachmann, the young art dealer in my novel, is not Otto Wacker. Most of my characters have no real-life counterpart and I have not cleaved to the historical record, in so far as there is one. I have altered and invented at will. On several occasions I considered drawing on the facts, only to realize how improbable or even fanciful they were. Instead I chose to make up my own. Fiction, unlike the truth, cannot defy belief. As for where the story of my novel came from, I can say only that it came, in rushes of realization or seams unpicked and resewn so often I can no longer remember where they started, in conversation, in reading, in that moment just on waking in the morning, still half asleep. Little by little, they came, Julius and Emmeline and Frank and all the others, moving slowly into the light, their features and their natures resolving and crystallizing as they got closer until it was not I who instructed them but them me, until their story felt like something inevitable and true.

And I still don’t really understand how it happened.

Henry James once wrote that “the only reason for the existence of the novel is that it does attempt to represent life.”