As a reader of mystery, suspense, or crime novels, what comes to mind as a naturally dangerous setting? Perhaps isolated gothic castles, abandoned buildings, haunted houses, teeming inner cities, suspicious rural villages, merciless corporations, equally ruthless socialites, and anything related to the mafia or organized crime.

But have you considered the world of fashion as a setting rife with inherent danger?

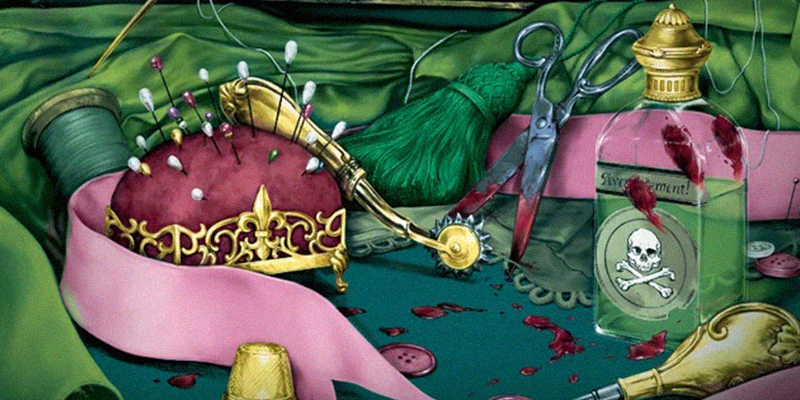

One aspect I love about fashion as a risky endeavor are the many ways in which a given fashionable item itself can become a murder weapon in the wrong (right?) hands. Ironically, this method can make the victim seem complicit in their own downfall. Imagine: instead of succumbing to a knife, a revolver, or a lead pipe, you’re felled by the elegant evening wear you paid a fortune for, specifically to be the envy of your peers.

Humans have a long history of leaping into what may well turn out to be highly dangerous fads without asking too many questions, making the world of fashion rife with potential plot bunnies. Anything goes, in the name of fitting in, or being seen as better than others. Does this painful and risky item make us look taller, thinner, handsomer, richer, or more powerful than my perceived competitors? Excellent, we’ll take two. What budding killer wouldn’t appreciate a murder weapon their victim would self-inflict willingly?

Some fashion trends kill more slowly than others. In the United States, we’re arguably still dealing with the reverberations today from a highly effective 1929 marketing campaign paid for by the American Tobacco Company, promoting cigarette smoking to the masses… including (gasp!) women.

Would you like to set something attached to your face on fire and breathe its acrid smoke into your lungs instead of oxygen? No? Fair enough. But how would you like to be the proud owner of “torches of freedom” symbolizing your equality with and emancipation from the misogynistic tyranny of men, in the name of feminism, seduction, glamour, and much overdue independence? Now we’re talking! Let the most rebellious feminists among us wave about our long black cigarette holders and a bejeweled case to flaunt our elevated new status.

One may argue that when “cigarettes as fashionable elegance” first took hold, we did not fully understand the deadly ramifications, and that is true. But nor did the world over immediately and collectively walk away once the truth became known. Cigarettes were too fashionable and cool. Instead of quitting, we invented new flavors and tools, each fad being perceived as more desirable than the last. While a suspense villain is unlikely to commit a multi-decade nicotine murder, the world of haute couture offers many other, more expedient paths to certain death.

Countless other widely adopted fashions have turned out to be shockingly harmful, causing secondary effects ranging from painful inconvenience to an early demise. Nor can we always claim we didn’t know jumping on dangerous trends in the pursuit of increasing our social status or achieving unnatural beauty standards was a risky endeavor.

In the 16th – 18th centuries, several such fads included cosmetics made with lead or arsenic. Many were touted as skin-lightening products (itself problematic, but not our current subject) such as the renowned “Venetian ceruse”, which could give its wearer a pallor indicative of high social status. It also gave adverse side effects ranging from nausea to reduced fertility to internal organ damage to death. But you would look very posh whilst it destroyed you from the inside out.

Again, we cannot claim we didn’t know what dice we were rolling. Famed high society hostess the Countess of Coventry died in 1760 at the tragically young age of twenty-eight due to her loyalty to the whitening power (and status signaling) of lead-based makeup. As far as murder plots go, the stage is already set. If you were a social or political rival, embittered maidservant, or cunning frenemy angling after the same suitor, how easy it would be to ensure your victim slathered herself in just the right products to ensure she would never again get in your way?

The 19th century brought a wide variety of dangerous fads to men and women alike. The first known printed use of “mad as a hatter” came in 1829, due to the well-known deleterious effects of chronic mercury poisoning from hat-making. The same arsenic used in taxidermy also made its way into hats, textiles, and decorative ribbons.

Health complications from tight corsetry have also long been documented, causing issues from inhibited breathing to internal bleeding to organ damage. Voluminous, flammable gowns and crinolines caused permanent scarring or painful deaths to women whose hems brushed too close to a candle or fireplace. Two of Oscar Wilde’s stepsisters tragically perished when one danced too close to a fire at a party, and the other attempted to put out the flames, only for her own dress to catch fire and kill her as well.

Women weren’t the only ones in danger from succumbing to fashionable clothing. Gentlemen’s tall, detachable collars were starched and tightened to a stiffness that cut off the carotid artery’s blood supply, earning the elegant coveted style the nickname “father-killer” for its lethality. When we’re willing to risk our lives for social cred ourselves, it wouldn’t take much for a murderer to give an extra little push in the right direction, and have their deadly efforts explained away by our willing commitment to keeping up with fashions.

Did we get wiser in the 20th century? Instead of poisonous skin-lightening ointments, we got carcinogenic tanning beds that can impart eye damage, premature aging, and skin cancer along with a glorious tan. A few generations earlier, the rage was radioactive cosmetics and related fads. Lipstick, face powder, ointments, hair treatments, suppositories, and “energy drinks” like Radithor, which memorably killed an American socialite by radiating his jaw right off.

Such trends can make highly convenient murder weapons for a killer who doesn’t want her crime to be seen as such. The bottle can be out in the open on the victim’s nightstand without raising any eyebrows from the authorities. What’s a little radium amongst friendly neighbors? A thoughtful housewarming present they’ll cherish for the rest of their life.

As an author, I adore this idea of gifting a future victim the means to their own destruction. If rich socialites and the upwardly aspirational were going to respond to clear and present danger with an elegant shrug anyway, then why not lean in?

For centuries, a key fount of Western fashion has been Paris, France. In The Protégée, I explore how far creators and consumers alike will go to get ahead, and how the hope to fit in or the ambition to rise above can make certain victims an easy target. Angélique is a seamstress and aspiring haute couture designer trying to make a living in the cutthroat world of high fashion—and enact revenge upon her enemies. Amongst other crimes and methodology, our 1860s antiheroine weaponizes high society’s desire to stand out amongst their peers by dressing them in poisonous dye.

Outlandish? Far from it. Scheele’s Green and Paris Green were two very real, and very dangerous, colors. The bright, cheery green was used in everything from wallpaper to clothing to furniture to paints to books to candles—and even in toys and candies. Contemporaneous newspapers detailed accounts of adults swooning at work or parties, and small children wasting away in their beautiful nurseries. Factory workers vomited bright green before dying.

Although Napoleon Bonaparte ultimately died of stomach cancer, his hair tested positive for arsenic exposure from his insistence on his walls being painted his favorite color: a sunny arsenic green. Decades later, a visiting dignitary complained to Queen Victoria after falling ill from spending the night in her fashionably green guest chamber. This was not her intent, of course, but in a thriller or mystery novel, anything goes. I had such fun with this concept in The Protégée.

With the wealthy and powerful so willing to risk their health and their lives in the name of high fashion, who can blame a revenge-focused anti-classist young murderess for surreptitiously helping her cruel, elitist enemies along the path to their own destruction?

***